Mireia Taribó and Tara Gomez make uncommon wines their way in the Santa Rita Hills of Santa Barbara County.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

LOMPOC — One of the winemakers is a native of an autonomous region of Spain whose family for generations made wine to accompany their meals. The other is a Chumash tribal member who honed her skills at the first winery ever owned and operated by California Native Americans.

Together, they run a Lompoc winery whose name invokes a Catalunyan word for “paths” the two have traveled to get here. This year, Mireia Taribó and Tara Gomez celebrate four years of Camins 2 Dreams, where they make uncommon wines their way in the Santa Rita Hills of Santa Barbara County. The venture is both rewarding and challenging for the BIPOC queer women who also happen to be married to each other.

But this year, Gomez and Taribó faced a struggle all too familiar to the couple — the unsettling wave of intolerant, hateful attacks on queer people happening throughout the country, including here in Southern California and the Santa Ynez Valley they call home.

Their response to the current anti-LGBTQ+ climate?

Make a Pride wine and donate 60% of proceeds to local LGBTQ+ organizations like Santa Ynez Valley Pride and the Rainbow House Inc.

“We wanted to do a Pride wine last year because it was the first one held in Santa Ynez, but we found out about it too late,” said Gomez. “Then with all the [anti-Pride sentiment] that’s going on in the valley, it’s disappointing but not really surprising. We knew this year we could do a wine for Pride and donate much more of the proceeds to these organizations doing work for the LGBTQ+ community here.”

Camins 2 Dreams’ limited-edition Pride red wine is a blend of all the grapes they used to make wine from last year’s vintage, representing the diversity and togetherness of “all the colors” for Pride. They have been selling it all month, culminating in a “Cheers Queers” Pride party they’ll host on Friday at their new tasting room in Lompoc’s buzzing Wine Ghetto.

The exterior of Camins 2 Dreams in Lompoc.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Standing out in the Santa Rita Hills

During a tour of the new tasting room, Gomez shows me a large wooden board with several rows of round holes.

“This is the riddling rack for the pét-nat,” she explains, as she pantomimes placing a bottle in one of the holes and turning it. “They stay here for about 28 days until we disgorge them.”

As if on cue, Taribó pulls a blue bottle from the fridge and holds it up to the light to show me the sediment. “This is what we get rid of during the disgorgement,” she says.

Gomez pulls out her phone and shows me a video demonstrating the process. She takes a bottle of pét-nat that has been stored upside down and holds it up to the camera so viewers can see the sediment collected in the bottle’s neck after 28 days of manual rotation on the rack.

“Every tasting room around here is going to have Pinot and Chardonnay. We won’t have any of that,” said Gomez, “because we wanted to do something different and work with grapes we really enjoy. We’re known for Grüner Veltliner and cool-climate Syrah. That’s what started Camins 2 Dreams.”

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

She then walks the bottle over to a metal box resembling a microwave oven missing its door. With one hand, Gomez holds the bottom of the bottle tight against her belly and angles the neck downward while she holds a long prying tool in her other hand. Timing and position are everything. She brings the bottle parallel to the floor, points the cap toward the back of the box, and pop! The cap flies away while foam and sediment bubble out like lava. Gomez places the bottle upright and steps back, her clothes covered in a fresh coat of yeast and grape matter.

“We lose some of the wine in this process,” explains Taribó, “so we have to fill it with the next bottle.” She fills and wipes each bottle by hand before using a manually operated machine to press on the caps. She and Gomez repeat this cycle, bottle by bottle, for the roughly 408 bottles of pétillant-naturel, a natural sparkling wine they make each year with the Austrian grape variety Grüner Veltliner.

Their pét-nat production encapsulates everything Camins 2 Dreams represents as a winery committed to making terroir-focused wines from underutilized grapes using sustainable, minimal-intervention methods.

Gomez, a Chumash tribal member, and Taribó, a native of the Catalunya region in Spain, blend their generational old-and-new-world knowledge of winemaking, rebelliousness and respect for the land to make what they describe as “underrepresented wines by underrepresented people.”

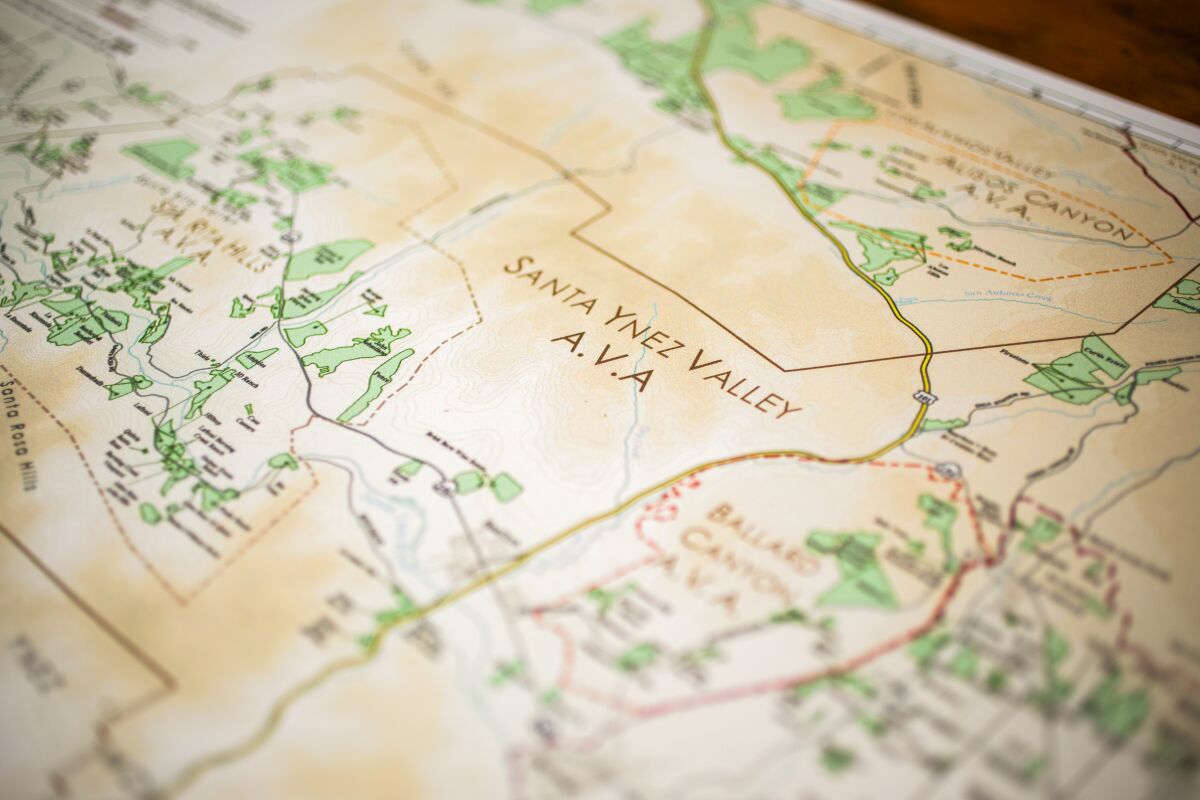

A map at Camins 2 Dreams tasting room shows the American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) in Santa Ynez Valley — one of seven in Santa Barbara County. Mireia Taribo and Tara Gomez experiment with cool-climate wines made with grapes from the more temperate Santa Rita Hills AVA.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The name Camins 2 Dreams incorporates the Catalán word camin (pronounced kah-meen), meaning “path.” As they tell it, Gomez and Taribó followed many “paths to their dreams,” including owning and operating a winery on Gomez’s native Chumash land. They also dream of someday making wine in Taribó’s Catalunya, an autonomous region of northeast Spain.

Camins 2 Dreams emerged as a side project while Gomez and Taribó worked at the now-defunct Kitá Wines, which was run by the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and bore the distinction of being California’s — and the nation’s — first and only Native tribal-owned and operated winery during its 12-year run from 2010 to 2022.

As winemaker at Kitá, Gomez rose to prominence and gained accolades for her Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc and other blends of Bordeaux and Rhône varieties that thrive across Santa Barbara County’s seven designated American Viticultural Areas.

As winemakers trained in chemistry and enology who yearned for a more balanced and natural approach to their craft as well as to experiment with lesser-known grapes, Gomez and Taribó began making a line of wines that reflected their shared vision of producing bright, balanced, food-friendly wines using sustainably farmed grapes and low-intervention practices.

“When we were putting our name out there, we knew we had to differentiate ourselves, not only with our story but through our wines and ways of making it,” said Taribó. “So, we said, let’s choose other varieties.”

Giving grape varieties their due: Think crisp and creamy Grüner Veltliner, floral, fruity Gamay and spicy berry Carignan.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Think crisp and creamy Grüner Veltliner from a grape commonly used in Austria to make everyday wine. Or wines from floral, fruity Gamay and spicy berry Carignan, grape varieties usually blended into anonymity with others and rarely given their own due.

Gomez, who has been making wine in her native Santa Ynez Valley since 2010, said, “Every tasting room around here is going to have Pinot and Chardonnay. We won’t have any of that because we wanted to do something different and work with grapes we really enjoy. We’re known for Grüner Veltliner and cool-climate Syrah. That’s what started Camins 2 Dreams.”

Most Syrah grapes grow in the warmer parts of Santa Barbara County and the Santa Ynez Valley, yielding heavier wines higher in alcohol content and with more structure and color from grapes left to ripen on the vine.

The incredible diversity of soils, landscapes and microclimates that distinguish the Santa Rita Hills AVA from others in Santa Barbara’s wine country mean that Gomez and Taribó can experiment with making cool-climate wines from a variety of grapes grown at small-scale organic, SIP-certified and biodynamic vineyards.

The diversity of soils from the Santa Rita Hills (samples shown here at Camins 2 Dreams winery), along with its distinctive landscapes and microclimates mean that Gomez and Taribó can experiment with making cool-climate wines from a variety of grapes.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Gomez and Taribó’s pét-nat also sets them apart from many of their winemaking peers. A sparkling wine fermented in the bottle with the yeast that comes from the vineyard — unlike Champagne, which requires a second fermentation with added sugar and yeast — a pét-nat appears naturally cloudy, and many winemakers leave the sediment in the bottle.

Hand-riddling is an old method that clarifies the wine without filtering or fining, which usually requires the use of additives. “Not many people do that in house, which is something unique. A lot of people send their stuff up to Napa or use other facilities to do it,” Gomez said. “It takes skill and time and patience.”

The one-eighth turn of the bottle by hand daily, slowly inclining the bottle each time until all the sediment collects, can take up to 30 days. The result is a “super-clean” pét-nat with no sediment that drinks dry rather than sweet from residual sugars. The dryness results from grapes picked earlier and an aging period of 10 months for the wine rather than the usual four to five months.

“They’re making this beautiful wine from a simple, nondescript grape usually used in Austria for table wine,” says Courtney Walsh, the Southern California sales representative for Amy Atwood Selections, a Los Angeles-based natural wine importer, producer and wholesaler.

“They work from a place of ‘what can we do with what we have access to,’ and they show us there’s so much more than Pinot and Chardonnay up there, that great wine can be made from underrepresented varietals like Gamay and Carignan,” said Walsh, who occasionally joins Gomez and Taribó for bottling and other winemaking tasks in Lompoc.

Gomez and Taribó also make rosé, Grenache and a blended red wine in addition to their signature Grüner Veltliner and Syrah wines. This year they released their first bottles of Albariño and Graciano, Spanish grapes that grow just as well in the Santa Rita Hills as they do in northern Spain.

“That’s why we love Santa Rita Hills. We can play with all kinds of different grapes for more acidity and balance in our wines.”

“Our wines are not like the funky-cloudy ‘natty wines,’” said Gomez. “We are on the natural side of winemaking, but totally different from the norm of what people expect because our wines are clean.”

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Making wine, not vinegar

Natural winemaking is often called a “counterculture” with origins in France’s Beaujolais region, where a handful of vignerons rebelled and created a movement against the increasing industrialization of the wine industry in the 1980s. They returned to traditional methods of winemaking that preceded mass production.

Gomez and Taribó hedge at calling their wines “natural” because they don’t fit the preconceived notion of what people imagine it to be — grapes left alone to ferment on their own to create a “raw,” unfiltered, chewy wine.

“Our wines are not like the funky-cloudy ‘natty wines,’” said Gomez. “We are on the natural side of winemaking, but totally different from the norm of what people expect because our wines are clean.”

Taribó puts it more bluntly: “Vinegar is natural to me. Wine is not.” She says that the idea of a winemaker “doing nothing” to the wine simply isn’t true.

“You’re always doing something, from making decisions in the vineyard and when to pick, whether you decide to crush or not, or use stems or not, putting a cover on your tank or not, temperature control. Maybe you’re not using additives, but you’re still doing a lot of things. Wine is not ‘natural.’ It’s a human thing to make.”

Gomez adds that their degrees in chemistry and enology, contrary to what some might believe, actually give them an advantage as minimal interventionists.

“To have two winemakers, plus two who know chemistry who knew from early on what we wanted to do, I think that’s a plus-plus-plus, because not everybody has that experience. Our education comes in handy and helps us make wines that are really stable or that will age better or don’t have problems with aroma or taste issues.”

Camins 2 Dreams makes rosé, Grenache and a blended red wine in addition to their signature Grüner Veltliner and Syrah. This year they released their first bottles made with Spanish grapes Albariño and Graciano.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Taking Pride

For as much as Santa Barbara is seen as a home for “maverick,” independent winemaking that departs from the conformity of Napa and Sonoma, women winemakers — let alone queer women of color — remain far outnumbered by their male counterparts in Santa Barbara County and California’s wine industry more generally. And in the Santa Ynez Valley, in the central part of Santa Barbara County, Gomez and Taribó report occasional incidents of racism and homophobia they experience as Native and immigrant lesbian women working in what they describe as a red part of an otherwise blue county.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“There are lots of conservative people in the Santa Ynez Valley, a lot of forces working against us right now,” said Coly Den Haan, owner of Vinovore wine shop, the first in Los Angeles to carry Camins 2 Dreams wine.

Den Haan grew up in Santa Barbara County and knows firsthand what Gomez and Taribó are up against.

These forces materialized last year in Santa Ynez Valley, which saw two men arrested and charged for burning a Pride flag they stole from a Los Olivos church and one outraged Solvang City Council member hurl names and epithets at the LGBTQ+ community over pride banners — compelling even the mayor of Copenhagen, Sophie Hæstorp Andersen, to write a letter to them expressing her disappointment at their “opposition to Pride” and rejection of Pride banners in the Danish-themed town.

“Camins 2 Dreams are really putting in the work in the community as openly out queers. They are people I want to champion as a queer businesswoman in wine,” Den Haan said.

As mentors and leaders in their community, Gomez and Taribó are poised to lead the way for the next generation of queer women BIPOC winemakers in California.

“At the end of the day,” said Taribó, “we’re trying to make wines that we really enjoy and are proud to share with people.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Food and Drinks News Click Here