It is only a single gallery, but some of the most glorious drawings of the 20th century fill it — drawings made by a pen that skims paper as vibrantly and beguilingly as stones bouncing on water.

There is no surface that David Hockney cannot capture in a few strokes: a café table crawling with ants in Luxor; sun-bleached, sharp-angled modernist facades on a Los Angeles boulevard; a French provincial hotel’s parquet floor illuminated as light falls across ornamental iron balcony railings. Jowly ageing poets — W H Auden, Stephen Spender — resemble weathered cliff faces. The exuberance of London restaurateur Peter Langan bursts out through his busy kitchen worktop — lobster, colander, grater, wine glass.

Displayed on hot pink walls, Hockney’s drawings make one little room an everywhere. Consisting of more than 40 perfectly chosen pieces from private collections, many rarely or never exhibited before, Love Life: David Hockney Drawings 1963-77 at Bath’s Holburne Museum is a very sexy show.

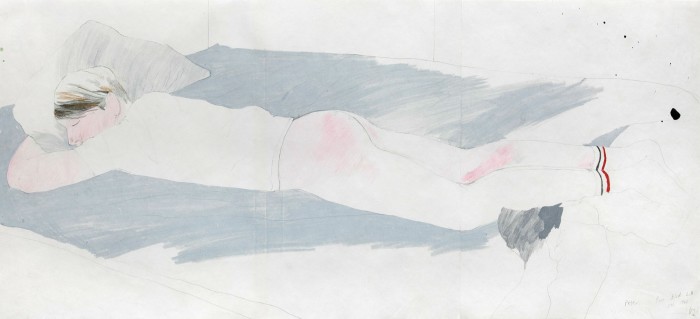

Even still lifes are travellers’ tales: the Arabic inscription of “these matches belong to David Hockney”; the pens posed, like a stand-in for the artist, to survey the view from the window of The Wyoming building in New York. They give a restless summer mood. And wherever Hockney goes, lithe young men are there, flopping into armchairs and sun loungers (“Nick, Hotel de la Paix, Geneva”, dapper with long hair and bowtie; “Gregory, Chateau Marmont”, languid in Hollywood), or sinking into pillows. “Dale and Mo” hug on Hockney’s bed in Notting Hill. Stretched out in mid-Atlantic (on the QE2) is “Peter Feeling Rough” — though not so rough that his long back, shapely legs and buttocks aren’t provocatively emphasised.

These drawings are intimate enough to invite you into the drowsy quiet of the encounter, broken, you imagine, by the tap of the pen whipping across the page. Hockney insists on silence for ink drawings: “You can’t make a line too slowly, you have to go at a certain speed, so the concentration needed is quite strong . . . You have to do it all at one go . . . it’s harder than anything else; so when they succeed, they’re much better drawings.”

The concision is marvellous: a reduction to essentials plus a few telling details. Metropolitan Museum curator Henry Geldzahler leans back, absorbed in a book, against puffed up cushions as plump as he is — but the cigar held prominently between his fingers asserts power, denies softness. “For Sleepy Kas” depicts dealer Kasmin napping on the grass; always alert, he’s kept his round tortoise-shell glasses on, and behind him the tree trunks, a mere couple of lines, are towering versions of his thrusting horizontal form.

The ink drawings fizz with energy and a brittle truthfulness. Those in coloured pencil are as evocative of character and the moment, but the effects are gentler. Slumped into a green fabric couch and looking discomforted, “Ossie Clark in a Fairisle Sweater” in 1970 is already as troubled as he is hip. The same year his wife Celia Birtwell, blonde curls, black-rimmed eyes, holding a cigarette, is cool as cucumber in a flouncy, romantic multicoloured dress. Her Mies van der Rohe chair imitates her body — curvy, slimline.

At the time Hockney was struggling to “paint the relationship of these two people” in his famous double portrait “Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy”. In the drawings, Ossie’s wary look and lounging posture, Celia’s control yet wistfulness, anticipate the painting.

Although each work here stands alone, together they reveal experimental processes and shifts in Hockney’s thinking. In his twenties and thirties he was at once authoritative and innovative, as enthralled by discovering places and people as by formulating new ways of making images.

The dealer Offer Waterman, who in 2015 organised a similarly excellent London show of the drawings, believes that particularly after 1966, when Hockney met 18-year-old Peter Schlesinger, “he started looking at naturalism as a way to use his work to get closer to him, so these are some of the most intimate drawings of his career”.

That year’s “Peter”, half-naked, wearing bright, striped socks, is typical of Hockney’s blend of eroticism and wit. In 1972, Peter is still the full-lipped beautiful boy, now clothed — striped braces, smart shirt — and gazing sadly, distantly: the drawing marked their unravelling relationship. “Gregory in Golf Cap” follows — a limpid portrait of Hockney’s new boyfriend Gregory Evans with Cupid smile, cascading curls, all dragonfly grace.

The progression of drawings in Love Life — the phrase is Hockney’s, he daubed it on the walls of his 2017 Centre Pompidou retrospective and now adds it to his signature — demonstrates the autobiographical impulse of his oeuvre. Signalling his rejection of the abstraction dominant when he left art school, he called his first solo exhibition, in 1963, Pictures with People In.

It could stand as a subtitle here, yet by the early 1970s he felt, he said, “caught in the trap of naturalism”. A prodigy as a draughtsman — rivalling Picasso as a natural master of line — Hockney had, sooner or later, to negotiate with that easy virtuosity to stop going stale.

His drawings, while capturing visible reality, also point to a way beyond straightforward representation. So superbly does he achieve three-dimensional volume and weight by line that he hardly needs shading or spatial recession: the glass, tea-cup, bottle, book in the sparse conjuring of a sultry Provencal afternoon “Vichy Water and Howard’s End, Carennac” for example.

In 1973 Hockney moved to Paris and became interested in allying himself to French tradition. Degas’s contre-jour effects and Matisse’s abstracting simplification and luminosity, as well as the French pictorial trope of seeing the world through a window, all play a role in “Louvre Window, Contrejour, Paris”, where muted light filters through a golden blind in an architectural setting as rigid as the clipped lawn of the Tuileries Garden outside.

The underlying theme here, how nature is framed by art’s formal concerns, is reprised in the wonderful final piece “Tulips and Painting” (1977). Its conceit is a picture within a picture, the foreground vase no more or less “real” than the background, which consists of a fragment of Hockney’s landmark, perspective-defying painting “Self-portrait with Blue Guitar” created the same year.

In the small image of inky tulips beginning to splay out into sculptural patterns, much that defines Hockney’s genius is distilled: acute observation, graphic brilliance, crystalline stylisation, sense of time passing, games with pictorial space. Love Life looks back, forward, celebrates the present and — especially when followed by lunch in the Holburne’s magnificent garden — is as life-affirming as its title implies.

To September 18, holburne.org

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here