The earliest work in Lubaina Himid’s joyous exhibition at Tate Modern is an absurd beach scene. In 1984, Himid reimagined Picasso’s classicised “Two Women Running” as a pair of black lesbian lovers, hands entwined, hurtling across a pink curtain. Their dresses are actual fabric, boldly patterned, and an actual leash holds four geometric wooden dogs with bared rectangle jaws and triangle teeth, champing at the bit; they add momentum, and craziness. Behind the women, silhouettes of white bald heads are buried up to the neck in sand — men going nowhere. The installation is called “Freedom and Change”.

For four decades, Himid has cut out large, often life-size, figures, both freestanding and painted on canvas, and arranged them in tableaux that reimagine history or art history from a black perspective. Born in Zanzibar (now Tanzania) in 1954 to a black father and white mother, she has lived in the UK since the age of four months. Although her sources are diverse, she works heavily with British artists, descending from Hogarth — narrative, comic, lavish in detail, bursting with social critique — and Victorian caricaturist George Cruikshank to Pop Art’s clean lines and David Hockney’s flat, lucid compositions, combined with a training in theatre design. She was awarded the Turner Prize in 2017 — the first black woman to win.

Tate’s launch of her exhibition to run concurrently with its Hogarth show (at Tate Britain) is inspired; the juxtaposition underlines Himid, still relatively unknown, as a mainstream voice — a Hogarth for today, a modern moral chronicler.

She came to prominence in 1986 with “A Fashionable Marriage”, an assemblage of 11 painted wooden figures, embellished with textiles, newspaper, foil, derived from Hogarth’s “The Toilette” in “Marriage a-la-Mode”. In Himid’s version, Hogarth’s dissolute countess is Margaret Thatcher, her illicit lover Ronald Reagan — lounging on a stars-and-stripes divan, missiles thrusting from his crotch. A subplot is a mise-en-scène of bewigged, foppish art lovers (“The Collector”, “The Funder”) and scrawled Picassos — the snooty, exclusive, white 1980s art establishment.

There is, however, hope. The two black servants from Hogarth’s painting have crossed gender: one towers, queenlike, over everyone else, the other — based on Himid’s then girlfriend, poet Maud Sulter — perches watchful, smart, self-possessed, on a trunk with a pile of books. The pivotal figure, she symbolises education as the tool to “allow black women to escape oppression”.

“It wasn’t made as a great work of art,” Himid says, “it was made as a furious caricature of the day.” The work seems nostalgic now; it brings to mind 1970s-1980s student agitprop — homespun, warmly chaotic, in your face: a period piece. Yet that is to misremember the age: in 1986, Himid recalls, “it was greeted with horror because you [didn’t] see work that was that critical . . . of white society.” As a result of the negative reactions, Himid left London to live in northern England.

“Marriage” contains the germ of everything since: the pop-up aesthetic, storytelling impulse, the tightrope between playfulness and rage. Twenty years later came “Naming the Money”: 100 painted wooden life-size figures, extravagantly dressed as musicians, dancers, craftspeople. Each represents a black servant, a status symbol in rich European 17th- and 18th-century households, and is inscribed on the back with a potted biography imagining his or her individuality, identity — their naming, in a repeated formula: “My name is Olusade. They call me Jenny. I used to cure diseases. Now I make the tea.”

This exuberant spectacle is Himid’s masterpiece and at the core of her art. To express the joy of making, imagining — the survivor’s tale — rather than describe atrocity is very much her answer to historical trauma. So there is no escaping disappointment that Tate does not show “Naming”. In its place is a related sound piece: recitations of the servants’ names and occupations interspersed with global music — John Coltrane, baroque viola da gamba harmonies, Buena Vista Social Club.

It’s poignant — an evocation of ghosts, identities stolen, vanished. It plays, incongruously, from speakers in a gallery containing only an empty bike shed. It also spills out across the show, and overlaps, like waves, with the roar of the rushing sea — soundtrack to an installation of giant painted oars leaning against a wall, “Old Boat/New Money”.

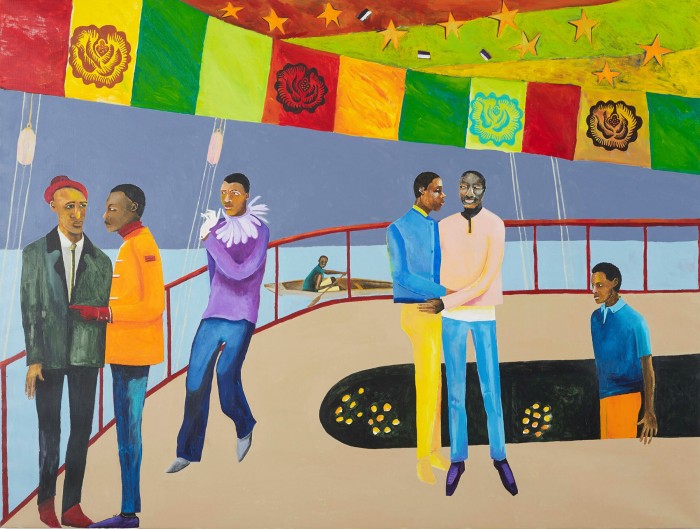

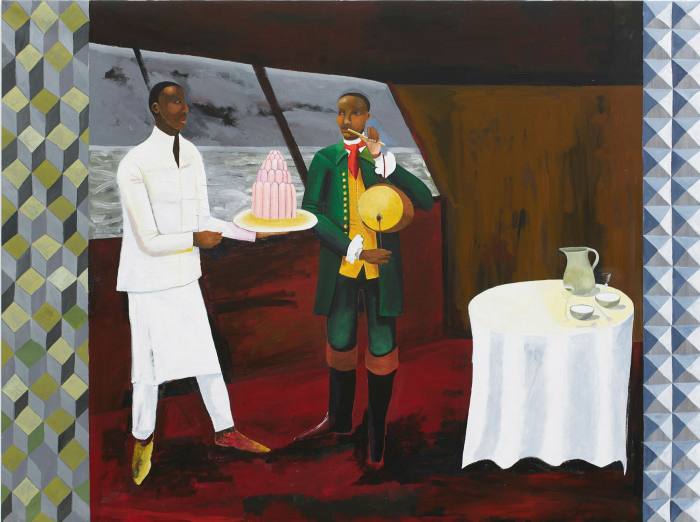

Together — and this is where you see and hear Himid the set designer most dazzlingly — the sounds float over the central gallery showcasing the painting series “Le Rodeur” (2016-17). The title refers to an illegal French slave ship whose entire human cargo, plus most crew, went blind during a voyage in 1819; three dozen slaves were thrown overboard.

How to paint fear? In paintings crisp and flat as stage sets, Himid depicts a contemporary transatlantic cruise where perplexed, then terrified, guests — hip young black travellers in razor-sharp bright suits and dresses — tilt, sway, hold on tight, as their sight fails. One woman has a bird’s head with beady yellow eye, another an eye emblem on her designer coat. A tall, unsteady waiter offers a jelly tower as wobbly as he is. Outside, the grey sea churns. Inside, a big diagram of a lock dominates.

I had thought Himid a so-so painter until encountering “Le Rodeur”. This inventive series swells above her other two-dimensional works: it distils her flair for theatre on canvas; it claims as normal everyday affluent black lifestyle, yet historic horror resounds. And it has never been as powerful as here, the music reiterating the fate of those on board — slavery or death on the heaving sea. Himid hopes that “the music is saying ‘be part of this installation’, not ‘look at it’”.

You need a little patience with this exhibition. Himid is uneven, and the opening galleries set an unfortunate tone of love-fest whimsy: a wraparound text piece “Our Kisses Are Petals, Our Tongues Caress the Bloom”; “metal handkerchief” paintings representing tools — screwdriver, pulley, saw — underlined with double entendre quotations from instruction manuals to “ensure sufficient space”, “provide adequate protection”, “keep moving parts lubricated”. Flags embroidered with body diagrams and twee inscriptions — an eye (“Why are you looking”); a heart (“So Many Dreams”) — are puerile. Portraits of black men painted on/incarcerated in drawers are sentimental, obvious.

But then there are the carts: “Feast Wagons” lined with tapestries of things we instinctively hate — spiders, scorpions — as analogies for how we demonise the other, especially refugees fleeing to our neighbourhoods with, metaphorically, their scant belongings piled into such carts. Didactic, yes, and affecting. They remind us that Himid is not just heir to Hogarth but to Brecht. She is a benign Mother Courage, following trouble and disaster with her art-cart — an irrepressible witness to our times.

November 25-July 3, tate.org.uk

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here