Think of Jane Goodall and the image that comes to mind is that somewhat magical moment when a baby chimpanzee reached out and touched her nose, connecting two species in a gesture that took the world’s breath away.

Images like that one from the 1960s helped Goodall get word out of how gentle these primates could be, how endangered, how like us.

Working in the same field at the time were Dian Fossey and Biruté Galdikas, all three handpicked by Kenyan-British palaeoanthropologist and archaeologist Louis Leakey for their credentials and their unusually passionate interest in primate behaviour. The nickname they acquired was rather derogatory, Leakey’s Angels. But they persisted for decades and changed how their field was viewed.

They were rare examples of women ecologists occupying the centre of their frame. It is true of most sciences that women tend to work in smaller numbers, rather invisibly, their achievements credited to them decades later, sometimes generations later (as with the women mathematicians who made Neil Armstrong’s Apollo 11 mission to the moon possible, and the women code-breakers who helped the Allies win World War 2).

How many Indian women ecologists can you name, for example? A rush of men’s names comes to mind, in a range of age groups. But have you heard, for instance, of J Vijaya, India’s first woman herpetologist, who tracked turtles across the country from 1981 until her death in 1987, aged just 28?

“Sadly, Viji died young, but by rediscovering the Forest Cane Turtle in Kerala’s Western Ghats she attained immortality, having the genus name of this enigmatic little chelonian named after her,” says Romulus Whitaker, founder of the Madras Snake Park where Vijaya volunteered as a teen. Previously called the Heosemys silvatica, it was renamed the Vijayachelys silvatica in her honour.

“There has been no dearth of women ecologists in India,” says Bittu Sahgal, environmental activist, writer and founder of Sanctuary magazine and the Sanctuary Nature Foundation. He goes on to name poet and environmentalist Sugatha Kumari; and anti-globalisation and food sovereignty activist Vandana Shiva.

“It’s just that these women had to spend 90% of their time fighting gender biases and only got 10% of their time to actually do what they wanted and needed to do.” Generations of women have struggled to be consulted, valued, seen. “What they were fighting wasn’t a glass ceiling, but an iron ceiling,” Sahgal says.

As with a number of professions even in the 21st century — chef, soldier, cop, bus driver, to name a few — there is the sense that the work of an ecologist will be too hard, the conditions too gruelling, the danger levels too high. The pressure starts at home, and expands outwards. Questions such as how will you do it, and who’s going with you, become hard to answer. “Added to the family pressure and the pressure of biases was a third — that there was virtually no money in this profession,” Sahgal says.

The women ecologists Wknd spoke to say it’s still difficult to convince mentors to send them out into the field, convince male colleagues they won’t be a liability, and that it’s even sometimes hard to get permission for routine fieldwork from forest officials. “Patriarchy is omnipresent and a woman is often limited by invisible boundaries, not just in this field but in many others,” says ecologist Tiasa Adhya, one of seven featured in this spread. “I am glad that, in addition to many conservative women, I also met women who are like beacons and who inspire younger ones to become bolder and stronger.”

Things are changing, says Mousumi Ghosh, ecologist, conservation biologist and academic dean at the Nature Conservation Foundation. “Today we don’t just have women role models, but women role models with diverse lifestyles. Many women who succeeded back in the day had to choose either a career in ecology or a family life, and that would be discouraging too. So many such things have changed.”

In recent years, “thanks to India’s burgeoning wildlife and ecology departments in colleges and universities, and thanks to organisations such as the Nature Conservation Foundation, Bombay Natural History Society, World Wildlife Fund – India, Wildlife Trust of India, Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Agumbe Rainforest Research Station and Dakshin Foundation, the job market for wildlife work has never been better and there are plenty of strong-willed women to fill these expanding niches,” says Whitaker. “The same is true of the forest departments of several states, where women are more visible in field positions like guards and foresters.”

The field of ecology is fairly young, there is much to do, urgent work needed, and the range of subjects extraordinary.

Here, then, is a look at seven Indian women doing extraordinary work in the field — from getting communities in Assam to understand and love a bone-swallowing bird, to protecting the nests and homes of endangered animals, and studying evolving diseases that could have implications across species — and for us.

.

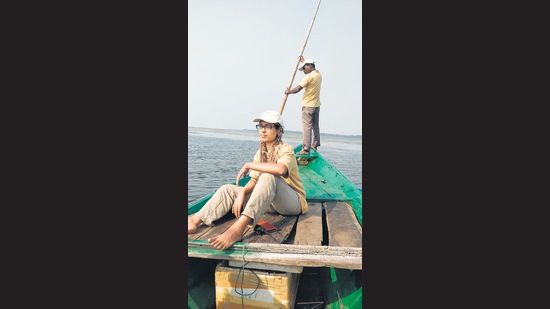

A future for the fishing cat: Tiasa Adhya

“This is the time to fight for the natural world,” says ecologist and conservationist Tiasa Adhya, 35. “Identify your strengths and try to understand how you can contribute to the fight.”

Born into a family of nature lovers in Kolkata, Adhya says she wanted to be a conservationist for as long as she can remember.

In college, she trained as a biologist. She began working in conservation at 22, with community development projects and biodiversity surveys in the Sunderbans. A traumatic experience with sexual harassment that went unaddressed at an NGO has prompted her to operate independently since then.

Mentors such as Vidya Athreya, now director of Wildlife Conservation Society – India inspired her to work outside protected areas; American small cat conservationist Jim Sanderson opened her eyes to small cat ecology and conservationist Ajith Kumar, affiliate scientist at the Centre for Wildlife Studies, was always at hand to help with advice during difficult phases of her work and life, she says.

In 2010, Adhya co-founded The Fishing Cat Project (TFCP), in an effort to protect this rare feline and its wetland habitats. “My co-founder Partha Dey inspired this project by connecting the dots: Fishing Cat — Wetlands — Climate Change — Us,” she says.

The fishing cat is a highly threatened species globally, classified as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. It gets its name from the fact that fish is its primary prey, and it has evolved to hunt this prey by developing a water-resistant double-layered coat of fur, webbed feet, and half-sheathed claws that help it hook fish. “These physical adaptations are not present in other cats,” Adhya says.

Adhya’s project is now the world’s longest-running project on this species, which is so elusive that it is one of the least-studied and least-understood wildcats in the world.

The project has had some remarkable achievements. In West Bengal, it supported NGOs such as PUBLIC and HEAL to protect the Dankuni wetlands from construction and development activity, by raising funds for the legal battle through online crowdfunding platforms and by collecting ecological data.

In Chilika, Odisha, driven by TFCP, the Chilika Development Authority (CDA) adopted the fishing cat as the official ambassador of the lake, in 2020. It also led to the initiation of a year-long patrolling and monitoring initiative involving local fisherfolk in collaboration with CDA. Data is being collected on natural history, behaviour and diet.

Volunteers have also worked with local communities and the forest department to reduce bird poaching, which is an indirect threat to the fishing cat, which can sometimes end up with injuries from wire traps laid on the ground.

“Adhya has worked to sensitise the community and put the fishing cat at centrestage,” says Susanta Nanda, chief executive officer of CDA. “She’s working with communities to protect birds too. Community participation plays a huge role in conservation of an ecosystem.”

Her work feels more urgent than ever amid the climate crisis, Adhya says. “With the erratic weather, disruption of food chains, scarcity-driven war looming in the near-future, who would the world turn to but ecologists,” she asks. “I feel that I have much to learn in order to become an ecologist and be a good conservationist. There is no time to relax.”

She sees her job as a vital mission. It’s a powerful thing, she says, to face and attempt to rise above one’s deficits for a larger cause.

.

Birds as a bellwether: Ghazala Shahabuddin

How does biodiversity respond to changes in land use; how can we manage forests differently so as to manage them better; why is it that some wild species can live alongside us and some can’t? Ghazala Shahabuddin uses birds as indicators to try and find answers to such questions.

Since her PhD in the ecology of fruit-feeding butterflies in the forest fragments of Lago Guri, Venezuela, Shahabuddin has spent decades researching biodiversity, forestry and ecology; conservation-induced displacement and community-based conservation; and wildlife policy, in India. She is currently a visiting professor of environmental studies at Ashoka University, and is involved in long-term research on the avian communities of the Kumaon Himalayas.

She and her team of research associates have discovered, for instance, that the disappearance of hardwood oak-dominated forests — they’re being replaced by the more commercially viable chir pine, as well as by tourism infrastructure and highways — is causing a decline in the population of birds such as woodpeckers and thrushes.

Once the oaks are gone, the insect populations suffer too, and this has a cascading effect on a range of insect-eating bird species such as flycatchers and warblers, some of whom are so sensitive to changes in habitat that they were already seeing lifecycles affected by the changing climate.

Because places like the western Himalayas have hardly any ecological studies,” Shahabuddin says, “scientists don’t know enough about these fragile forests to adequately plan for the mounting threats they now face.”

Part of her role, as she sees it, is to communicate what is happening and what the individual can do to help. That’s one reason she collaborates with the Titli Trust, which promotes nature-based tourism, a crucial aspect of preserving ecologies in rural Himalayan regions. Shahabuddin also writes on ecological issues in the media.

The joy of watching nature at work, despite all the challenges, is what keeps her going, she says. “I think the question we need to answer is: Where does this diversity come from, and, as we expand our own footprint on the planet, how can it be preserved?”

.

A deep dive into the life of the Indian skimmer: Parveen Shaikh

Whether in the wild or in a bird book, the Indian skimmer, a black-and-white bird with a bright orange-yellow beak, is unmissable. It gets its name from the way it feeds, skimming the surface of the water using its longer lower mandible to catch fish as it goes.

“The skimmer first caught my attention in a bird book,” says Parveen Shaikh, 33, a research biologist with the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS). She began studying the bird at the Chambal sanctuary, spread across parts of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, in 2017, and has been monitoring their population and nesting success since.

The Indian skimmer is primarily found around wetlands and along large rivers in the Indian subcontinent. As these habitats have either vanished, shrunk or been degraded, the bird’s numbers have plummeted. Today, the species is confined to India and Bangladesh, with very few sightings in Pakistan, Nepal and Myanmar.

In India, the Chambal, Mahanadi and Ganga river basins are the bird’s primary nesting grounds. As Shaikh and her colleagues continued their research into the bird’s population and nesting success, they knew the clock was ticking. In 2020, their fears were realised when the Indian skimmer (Rynchops albicollis) was classified as endangered by IUCN, which estimates that there are just 2,000 to 3,000 of these birds left.

It’s not an easy bird for ecologists to study. These birds nest on sandbars, which are exposed to predation by dogs and jackals. Sand mining is an emerging threat for nesting colonies and it might have a long-term effect on sandbar formation.

Over two years, Shaikh and her team identified nesting islands across the Chambal sanctuary, assessed their status and threat levels and, in 2021, with funds from BirdLife International’s Preventing Extinction Programme, SBICAP Securities, and the Conservation Leadership Programme collective, launched the Nest Guardian Initiative.

This programme trains and pays groups of villagers from the area to monitor and protect vulnerable nesting colonies of skimmers. They chase dogs and jackals away, for instance, and redirect cattle.

The beauty of this initiative is its simplicity. Through 2022 and 2023, Shaikh will monitor its impact to see to what degree it can help improve the nesting success of skimmers.

The programme will then either be made permanent or rethought on a larger scale.

Because the disappearance of the skimmer isn’t just about the skimmer, Shaikh says. It indicates that things aren’t right with the river, with the sandbanks and with the wetlands.

.

Through the eye of the tiger: Latika Nath

Latika Nath, 51, has spent the better part of her life, over 30 years, studying tigers. Her father, Lalit Nath, a former director at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, was also a conservationist, served on the Indian Board of Wildlife, and was a key driver of the animal conservation movement in India in the 1970s.

Nath spent much of her childhood immersed in nature, visiting jungles and forests across the country. She was initiated into the wilderness when she was three weeks old. By age six, she says she knew the word “ecologist” and knew it was what she wanted to be.

She went on to get a Master’s degree in elephant-human conflict resolution, and became the first woman biologist in India with a doctorate on tiger conservation and management from Oxford. None of which has made the road any easier for her, she says. Young and supremely qualified, she was often told to “know her place”. “I’ve had a professor in India say to me, ‘I’m a Rajput and whatever I say is written in stone’.”

For 25 years, Nath has opted to work largely independently at the grassroot level to promote tiger conservation among tribal communities in the buffer zone of the Kanha reserve in Madhya Pradesh. She took up photography as a means of self-healing after a difficult divorce, and found a second passion in the lens. Her images of tigers, lions, cheetahs, jaguars, snow leopards, clouded leopards, elephants, Gangetic dolphins and more have attracted over 37,500 followers on Instagram (@latikanath) and over 56,000 on Facebook (@nathlatika).

“For me photography captures the aesthetics of cats, something which science fails to do,” she says. “Photographs are a more effective means of communication with the public too.”

She’s now working on a new conservation programme with her partner, Vikram Aditya Singh. Hidden India is a high-end low-impact tourism model aimed at generating money for local communities, minimising human-animal conflict and protecting tiger habitats.

“We have to keep changing our approach and finding new things that work,” Nath says, “because when it comes to tigers — as with nature in general — there is no one size fits all. Even without us, everything is constantly changing.”

.

Training a hawk’s eye on bird diseases: Farah Ishtiaq

Farah Ishtiaq, 49, is literally one of a kind. The evolutionary ecologist has spent 20 years researching the ecology and evolution of vector-borne diseases in birds. “I specifically wanted to study the spread of malaria in birds because there was not a single scientist doing it in India,” she says.

The outdoors and birds have always excited Ishtiaq. “Since learning about the migration of Siberian cranes to the only wintering site in India, and finding a tailor bird’s nest in a bush as a child — how intricately the leaves were sewn together — I knew then that I couldn’t see myself doing anything else,” Ishtiaq says. The cranes, of course, no longer visit India.

Her one-of-a-kind field of study arose from a desire to incorporate genetics into her ecological research, so she could gain fresh insight into how certain kinds of diseases spread, evolve and diversify. She was offered a postdoctoral research position at the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Conservation Genomics and started out by studying avian malaria in Hawaiian birds.

“It was a life-changing experience,” she says. “Malaria and avian pox are blamed for 90% of the extinctions of endemic birds in Hawaii.” These birds were particularly susceptible because they had no natural immunity to malarial parasites that were introduced into their environment accidentally by European seafarers. (Incidentally, where humans are susceptible to one strain of malaria, birds are susceptible to many).

Her postdoctoral experience made Ishtiaq wonder: what other problems could birds around the world be facing as a result of increased globalisation?

For her second postdoctoral research position, as a Marie Curie Fellow at Oxford, Ishtiaq worked in the South Pacific islands of New Caledonia and Vanuatu, to understand malaria parasite biogeography.

In the last ten years, her research has focused on Himalayan birds, with the goal of better understanding the malaria parasite’s diversity and prevalence across migrant and resident bird species, and the impact of climate change on parasite and mosquito distribution.

The fieldwork can be extremely challenging, she says. Just getting to some Himalayan study sites can require a four-hour hike in freezing morning hours, to set up mist nets to catch birds. Mosquito sampling requires special light traps that need continual battery supply for 10 to 12 hours. For morphological identification, specimens should be as fresh as possible. And keeping specimens intact and fresh in remote field stations is a challenge.

With fieldwork restricted in the pandemic and new opportunities emerging in its place, Ishtiaq, now a senior scientist at the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society (TIGS), Bengaluru, has shifted focus. She leads teams of young researchers in that city who are using wastewater testing as an early warning system for the spread of Covid-19. Analysing wastewater helps scientists identify hotspots of disease and predict the next outbreak at least 15 days before it begins, she says.

The pandemic should teach us, she adds, that studying disease ecology is vital. “It’s a niche that needs to be exploited and investigated. India is rich in biodiversity, and we certainly have our fair share of problems at the intersection of human and wildlife health that require immediate attention.”

.

The ‘Stork Sister’ of Assam: Purnima Devi Barman

The greater adjutant stork used to be called many things: ugly, filthy, a pest, a bad omen. Then Purnima Devi Barman, 41, entered the fray.

Her Hargila Army or Stork Army, which operates in rural communities in Kamrup district, Assam, has adopted the bird — a gentle giant that typically stands at a height of 5 ft — and helped turn it into a cultural icon.

It, in turn, has turned her into an icon as well. Barman is now called Hargila Baido or Stork Sister.

It all began in 2007, when Barman, an ecologist who had taken a break from her conservation work to complete a PhD on the greater adjutant, was interrupted by a villager who had spotted a man cutting a tree in which one of these birds had built a nest.

“I rushed there and fought with the man, pleading with him to spare the birds their home. But I couldn’t save the tree,” she says. She returned to her desk, but couldn’t continue with her research. What would be the point of finishing her thesis on these birds, she remembers thinking, if they survived only on paper?

At best though, its total count is expected to be slightly more than 1,000 individuals. The greater adjutant stork is classified as Endangered on IUCN’s Red List and is classified as protected under India’s Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972. As of 2008, according to IUCN, there were an estimated 800 to 1,000 greater adjutants left in the wild.

After the incident with the bird and the tree, Barman returned to active conservation. “But I realised I had to change the perspective of the people towards this bird and involve communities,” she says.

She knew this wouldn’t be easy. Locals in rural Assam saw it as a scruffy scavenger which lived on garbage, fed on carcasses, and carried the remains of dead creatures into its nests. Even the Assamese name for the bird is rather horror-stricken; hargila is literally “bone-swallower”. (Its English name, adjutant, incidentally, comes from its awkward manner of walking, like a stiff march).

Barman decided to reach out through the women. “The women joined my meetings, albeit hesitantly,” she says. “They would laugh, but they would listen.”

To engage with them better, Barman organised events. She held laru-pitha feasts where all were welcome to come and eat the beloved delicacy of sweet coconut balls and rice cakes. As they ate, she talked about her love for the greater adjutant stork.

She organiseed cooking competitions in backyards, and used the opportunity to talk about why the hargila was so important for Assam’s forests. She organised theatre festivals where whole plays were written in which the hero was, you guessed it, her favourite adjutant. She held baby showers for newborn hargilas to discourage people from cutting down the trees in which they lived. “I would tell them, the hargila could have gone to any village in Assam, but it’s come to us, so it’s ours to protect, if we don’t then who will?”

From those small beginnings, Barman has built a network of 10,000 women activists committed to protecting this stork and spreading word about why it is precious. By associating festivities with the bird, Barman believes she helped foster a sense of pride in the rare creature. “Today, many women join because it is a matter of prestige to be a part of the Hargila Army.”

Barman, who has worked with the NGO Aaranyak since 2009, has received numerous awards over the years for her unique initiative. In 2017, she won the Whitley Award, also called the Green Oscar, and the Nari Shakti Puraskar awarded by the President of India.

Her greatest source of pride remains her army. “The hargila is like my own child,” says Kaamini Das, one of Barman’s network of eco-warriors. “The Hargila Army taught us our role in society, especially towards Mother Earth.” It’s given the women a mission and an identity, Das adds. “Our roles were confined to household chores. Today we are so proud that we are activists saving our hargila birds.”

.

Protecting India’s dancing frog: Madhushri Mudke

When Madhushri Mudke, 32, a researcher from Maharashtra, arrived in Manipal for her Master’s degree in physiotherapy, she was entranced by the town’s abundance of birds. She completed her Master’s, but the birds stayed with her. She switched careers and, since 2015, has been researching the impact of urbanisation on amphibian communities, particularly frogs.

Currently, most of her work is based in the Western Ghats, studying the threats and ecology of the Kottigehara dancing frog (so named because of its unique visual signalling style of foot flagging). As large mammals get most of the attention, she wanted to help preserve this little species, she says.

Mudke is also currently a PhD scholar with the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) in Bengaluru. Her research is funded in part by the Zoological Society of London through its EDGE fellowship, because the Kottigehara dancing frog is an Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered or EDGE species.

The Kottigehara dancing frog lives in permanent, primary streams in the Western Ghats. Pollution, dams and the clearing of forest land for use by humans is endangering the species. Mudke’s research attempts to understand its habitat requirements, to in turn help conserve its habitats. Each species thus saved plays a larger role in beginning to alleviate the biodiversity crisis, she says.

As part of the same mission, Mudke is simultaneously working to list the types of frogs found on the lateritic plateaus of Manipal. “We barely know what kinds of species are in these plateaus, and yet the region is being developed at an alarming rate and used as dumping grounds,” Mudke says. “Despite their uniqueness and complexity, these are referred to as ‘wastelands’ just because they are treeless. They may look arid and dry in the Indian summer, but they are teeming with life.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here