Hooves paw the ground, whinnies of fear rise with men’s shrieks and the clash of weapons in the stony desert, the flat plain broken by a single gnarled tree, where Alexander of Macedon, handsome, helmetless warrior, hair streaming, gaze as piercing as his lance, charges forward to kill King Darius. As he strikes, a Persian prince in iridescent yellow jumps forward and takes the blow, sacrificing himself so that Darius’s charioteer can flee to safety.

The narrative unfolds cinematically. Horses stampede over mutilated bodies. Darius, arm vainly outstretched to his dying relative, looks back — an incomparable expression of shock, pity, horror — as he is pulled away. Beneath the chariot a soldier, about to be crushed by its wheel, stares at his own reflection on a shield — confronting the instant of his death.

Based on a lost Greek painting made when memories of the 333BC Battle of Issus were still alive, the five-metre Alexander Mosaic, composed of 2mn tiny tesserae placed to represent astonishingly naturalistic figures and vivid emotion, is a glory of Naples’ National Archaeological Museum, but damaged and fragile. After years out of sight, its restoration, repairing cracks and detached tiles, smoothing bulges and hollows, allowing colour to shine, is unveiled on May 25, launching the exhibition Alexander the Great and the East.

This ambitious show, exploring Alexander as cultural rather than military leader, is staged to coincide with the marvellous Picasso and Antiquity, which opened last month — a superb, unique pairing. For today’s audiences, the chaos and pathos of man, beast and war in the Alexander Mosaic inevitably calls to mind the “Guernica” frieze of horror.

Picasso is presented downstairs, in the museum’s heart, the Farnese galleries — its foundational collection of ancient sculpture excavated in Renaissance Rome. The gateway is the heroic marble “Hector”, which Picasso emulated for his virile self-portraits — massive, muscular, tousle-haired, bearded — in the Vollard Suite’s “Sculptor and Model” series.

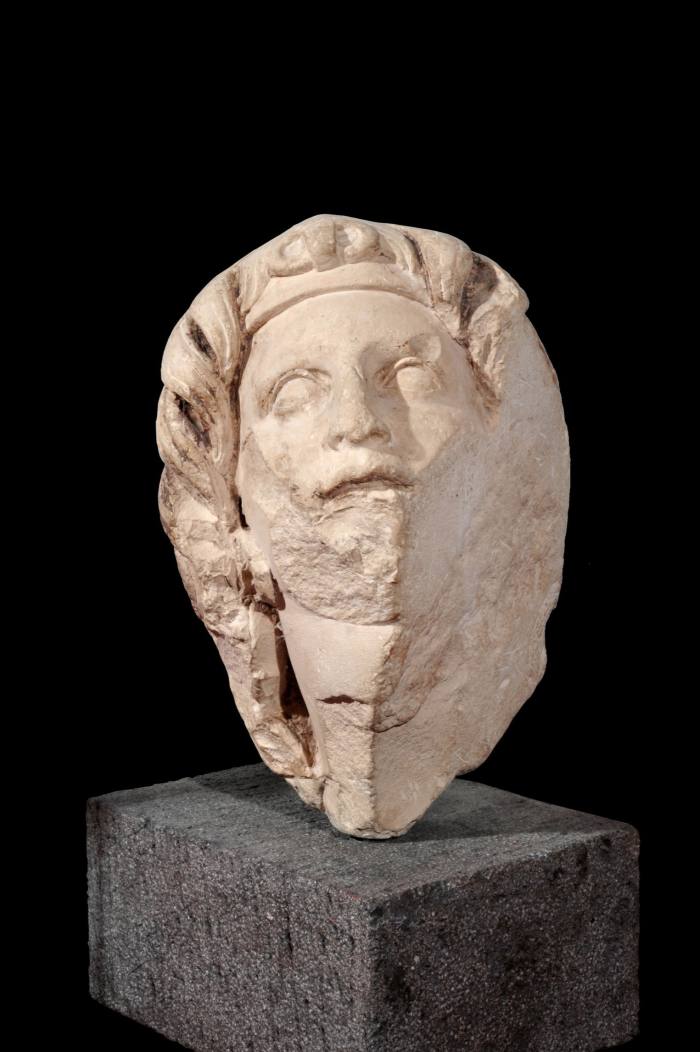

Upstairs, Alexander — astride his fierce steed Bucephalus in bronze with silver inlays; in an autocratic Roman marble head; as a beautiful Greek youth in terracotta; his face engraved on silver coins, topaz gems — presides in the Sundial Salon, the museum’s largest gallery, beneath a ceiling frescoed in 1781 with Ferdinand IV of Naples as patron of the arts.

Did Alexander, too, see himself spreading enlightenment, or did he conquer most of the known world for the usual reasons — power, prestige, loot?

Paolo Giulierini, the archaeological museum’s director, believes Alexander’s arrival in Babylon was pivotal; its rich culture allowed the imaginative young man, tutored by Aristotle, to conceive of an empire united in multicultural fusion. Coming from Macedonia, Alexander lacked an Athenian’s innate sense of cultural superiority. He enraged his loyal army by adopting Persian manners and encouraged his soldiers to marry Persian women.

Although under his rule and long after Hellenistic influence in art and thought spread as far as India, cultural exchange, this show demonstrates, flourished in both directions. A Buddha from Pakistan is styled as a lithe Greek god. A relief of monks in gorgeous classical drapery was excavated in Afghanistan. A Greek mosaic has Dionysus riding a tiger. On Egyptian coinage Alexander appears with an elephant skin, and in the delicate Egyptian sculpture “Alexander with Aegis”, a sensitive youth wears a goatskin fringed with snakes and Gorgon head — goddess Athena’s emblem of invincibility.

No exhibition can settle the case for Alexander’s motives, disputed for millennia, but Naples brings alive the framework for his thinking. Alexander saw himself as Achilles, bravest of the brave, obsessional, quixotic, and his closest friend and general Hephaestion as Patroclus. Stunning vases (6th century BC) depict Achilles’ weapons, Achilles and Ajax; the “Patroclus Vase” narrates his funeral games. Like Achilles, Alexander was devastated by his friend’s death, surviving Hephaestion merely by months.

In Naples’s archaeological museum, more than any other, the Homeric world, the myths in which Alexander was steeped, acquire visual immediacy. Few modern artists could hold their own here, but for Picasso the positioning is perfect: he visited Naples in 1917, and the colossal Farnese works influenced his turn to classical monumentality, while the Pompeiian frescoes renewed his interest in naturalism. Thus “Seated Woman” (1920), in which his wife Olga, heavy and sombre, resembles both a melancholy statue emerging from shadows, the pinks and whites of flesh tones and dress shrouded in grey, and the mournful draped figure in the fresco “The Sacrifice of Iphigenia”.

In the 1930s, Picasso’s Naples memories resurfaced in the “Minotaur” works, laying the ground for “Guernica” — depictions of the Minotaur precisely anticipate the bull’s head above the open-mouthed girl. Here these are juxtaposed with the largest antique sculpture ever excavated, the “Farnese Bull”, a woman sadistically tied to a wild beast. Picasso’s own rampaging bull and innocent girl in the most intense, multi-layered etching, “La Minotauromachie VII”, lent from Larry Gagosian’s private collection, resonates especially dramatically with the multifigured, turbulent Farnese piece.

Both these shows are bold celebrations of heroic white men whose achievements are today controversial — Alexander’s inescapably a colonialist’s story, Picasso’s art rooted in imagery of suffering women. How the archaeological museum chronicles this without becoming mired in culture wars is inspiring to anyone concerned with the role of venerable yet currently besieged western collections.

That these subjects are addressed at all is thanks to Giulierini, who since his appointment in 2015 has transformed a fusty, dusty museum, a scholar’s enclave, into a vibrant institution engaged with modern art and life today — an agora attuned to contemporary pleasures.

The museum’s tote bag features “Venus Callipyge”, tantalisingly lifting her robe to flash hips and buttocks. Vino Blu is on sale in bottles reproducing motifs from the rare translucent Roman cameo glass Blue Vase. The three-metre bronze “The Hero’s Dream” (2021), Christian Leporino’s portrait of footballer Diego Maradona as Nike, emblem of winged victory, with a child (the dreamer) and a football, soars in the Garden of Camellias. Studded with fragments of disused boats and architectural detritus, it is a democratic image of triumph wrought from urban decay, bringing the street into the museum.

It is also deeply classical, at home in the collection. Alexander and Picasso too are linked by the humanist ideal, distilled from imperfect life, which characterises every work here — sculptures human and affecting in their rhythm, dynamism, expressive force, sensuality.

This vast collection, graciously displayed with captions that neither patronise nor politicise, seems to me amply to accommodate contemporary ambiguities and uncertainties without losing faith in the icons of western art. Picasso’s Minotaur was his most aggressively macho alter ego, but the context here affirms its complexity — self-assertion, enlarged sympathy, despair — as he reconsidered classical tragedy during Europe’s dark 1930s.

This is a model of a museum joyously refreshed while remaining, as Luigi Spina, photographer for the Alexander Mosaic, writes, “a microcosm of the human spirit”.

‘Picasso and Antiquity’, to August 27; ‘Alexander the Great and the East’, May 25-August 28, mann-napoli.it

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here