A late-stage trial of an Alzheimer’s drug set to generate results within weeks is shaping up as a pivotal moment in a three-decade quest to prove that removing sticky amyloid plaques from the brain can slow down the disease.

The phase 3 trial is being led by Eisai, a Tokyo-based pharmaceutical company that has partnered US biotech Biogen to develop lecanemab. Earlier studies suggested the monoclonal antibody treatment can clear plaques known as beta amyloid that are at the centre of an increasingly acrimonious scientific debate over what causes Alzheimer’s.

A positive result could lead to approval of a new medicine for a disease affecting 50mn sufferers worldwide that has no known cure. It would be encouraging for Eli Lilly and Roche, which are conducting trials on similar drugs that could generate tens of billions of dollars in sales if they are proven to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s.

But scientists say disappointing test results would deal a significant blow to the so-called amyloid hypothesis, the idea that clearing clumps of toxic cells that bind together in the brain can slow the rate of cognitive decline in sufferers.

Alberto Espay, professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati, said some researchers had become far too tethered to the amyloid hypothesis, which has been tested in dozens of studies that have failed to provide conclusive proof that removing the plaques slows cognitive decline.

“We’ve run into a dogma,” he said. “And it is very hard to test new ideas when the overarching theme of funding is centred on the idea that removing amyloid must be the only way to go.”

Disappointing results might also act as a catalyst for a shift in funding for Alzheimer’s research, with some scientists arguing that promising areas of study and potential treatments have been crowded out by Big Pharma’s focus on amyloid.

The amyloid hypothesis is the most tested of the many theories of what causes Alzheimer’s, which range from an inflammation of some types of brain cells to the presence and formation of various proteins in the brain. It has been the focus of more than a fifth of the more than 2,000 clinical trials related to the disease as of 2019.

The botched launch last year of Biogen’s aducanumab — the first amyloid-clearing drug to win approval and the first new treatment for the disease in almost two decades — has served only to heighten doubts over similar drugs.

Aducanumab, which is sold under the brand name Aduhelm, was given the fast-track green light by US regulators despite questions over its effectiveness and the robustness of two late-stage clinical trials that underpinned its approval. Widespread scepticism among clinicians deepened further when the company priced the treatment at $56,000 a year, a move that also sparked a backlash among politicians and policymakers.

In April US authorities delivered a crippling blow to Aduhelm by severely restricting reimbursement by government-funded health schemes, a move that limits its use to a few thousand people taking part in clinical trials. Any similar amyloid treatments approved under the FDA’s fast-track procedure would face the same restrictions, a hurdle that Eisai acknowledges complicates the approval process for lecanemab.

“Yes I admit that it does raise the bar. That is why the design of the trial . . . is so important,” Ivan Cheung, US chief executive of Eisai, said in an interview.

In a bid to build public trust, Eisai is running one of the largest trials ever undertaken on an Alzheimer’s drug, enrolling 1,795 patients in the early stages of the disease. It has also sidelined its partner Biogen by assuming what Cheung describes as “final decision-making authority” as the drug moves through the regulatory process.

Eisai is aiming to match or better the results of an earlier trial that showed giving patients a 10mg dose of lecanemab every two weeks over 18 months can slow the rate of cognitive decline by 26 per cent, compared with those who were given a placebo.

It is using the Clinical Dementia Rating scale to measure the symptoms of dementia in patients in six categories, including memory, judgment and problem solving.

Critics allege this scale is an imprecise mechanism and question whether it is worth approving amyloid drugs that may only slightly reduce the pace of cognitive decline and that can cause life-threatening side effects.

But patient groups such as the Alzheimer’s Association say even relatively small delays in disease progression can provide significant benefits to people suffering a terminal disease.

“It could mean six more months in that stage where you can maintain your independence, enjoy your family and attend a wedding,” said Maria Carrillo, Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer.

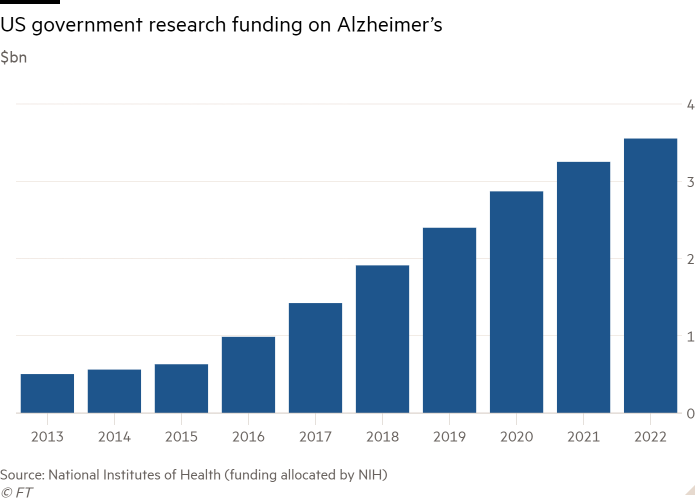

Despite the controversy over Aduhelm, Carrillo said it was an encouraging time for Alzheimer’s research, pointing to increased government funding and key findings from clinical trials.

Eisai said that following the Aduhelm controversy a result showing a rate of slowing below 25 per cent might “trouble” its FDA application for accelerated approval for lecanemab, a process that is due to conclude in January.

Under this fast-track process, the FDA could approve the drug on the basis that it reduces amyloid plaque and is only “reasonably likely” to predict a clinical benefit. Those were the same criteria used to approve Aduhelm, a contentious decision that prompted the resignation of three members of a committee advising the FDA on the drug.

Cheung said he was confident the lecanemab trial would be a success and asked that amyloid sceptics study the data before passing judgment. “Everything should be fact based . . . I hope we will have a fair debate,” he said.

For Biogen, success might help rebuild its tarnished reputation following the disastrous launch of Aduhelm, which sparked $1bn of cost-cutting, the departure of its chief executive and investigations by multiple US government agencies.

Ronald Petersen, director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, said if the lecanemab trial was a “flat-out negative” then it would not be good for the “amyloid hypothesis”. But he said it would not bury the theory altogether because of forthcoming results from late-stage trials of three drugs from Roche and Eli Lilly.

Petersen said his best guess was that one of the trials would show a positive clinical impact, although of a modest magnitude.

“This would give us a foot in the door for treatments because ultimately down the road its going to take combination therapy to have a voilà kind of effect,” he said.

“If all four of these [trials] really show no evidence of any kind of a clinical impact . . . it may just suggest we probably should look elsewhere for clinical targets,” he added.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Health & Fitness News Click Here