Starting this week, Apple is rolling out its version of “buy now, pay later.”

Using a short-term loan to finance a small or medium purchase — Apple says Pay Later loans will be available in amounts from $50 to $1,000 — is “sold like a no-brainer” to consumers, personal finance expert Carmen Perez said. “I’ve heard people say it seems like free money.”

Of course, there’s no such thing. Compared with traditional credit cards, there are few upsides to using any “buy now, pay later” program. And evidence indicates the existence of these loans can facilitate unhealthy consumer behaviors that can trap people in debt.

Apple Pay Later is elbowing into a crowded field: AfterPay, Klarna, Affirm, Zip and similar short-term financing companies constitute a fast-growing market. There were almost 10 times as many “buy now, pay later” (often shortened to BNPL) loans issued in 2021 compared with 2019, according to a report from the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau. The total value of those loans grew from $2 billion to $24.2 billion in that time period.

“The way that ‘buy now, pay later’ is positioned, it doesn’t seem like debt up front,” said Perez, who’s the creator of the budgeting app Much and part of a new women’s financial education initiative from Secret Deodorant.

But it is: “That’s still debt. You’re still on the hook for that. And there’s still negative consequences for that.”

Budgeting app creator Carmen Perez says “buy now, pay later” loans are “sold like a no-brainer” to consumers.

(Diane Bondareff / AP Images for Secret Deodorant)

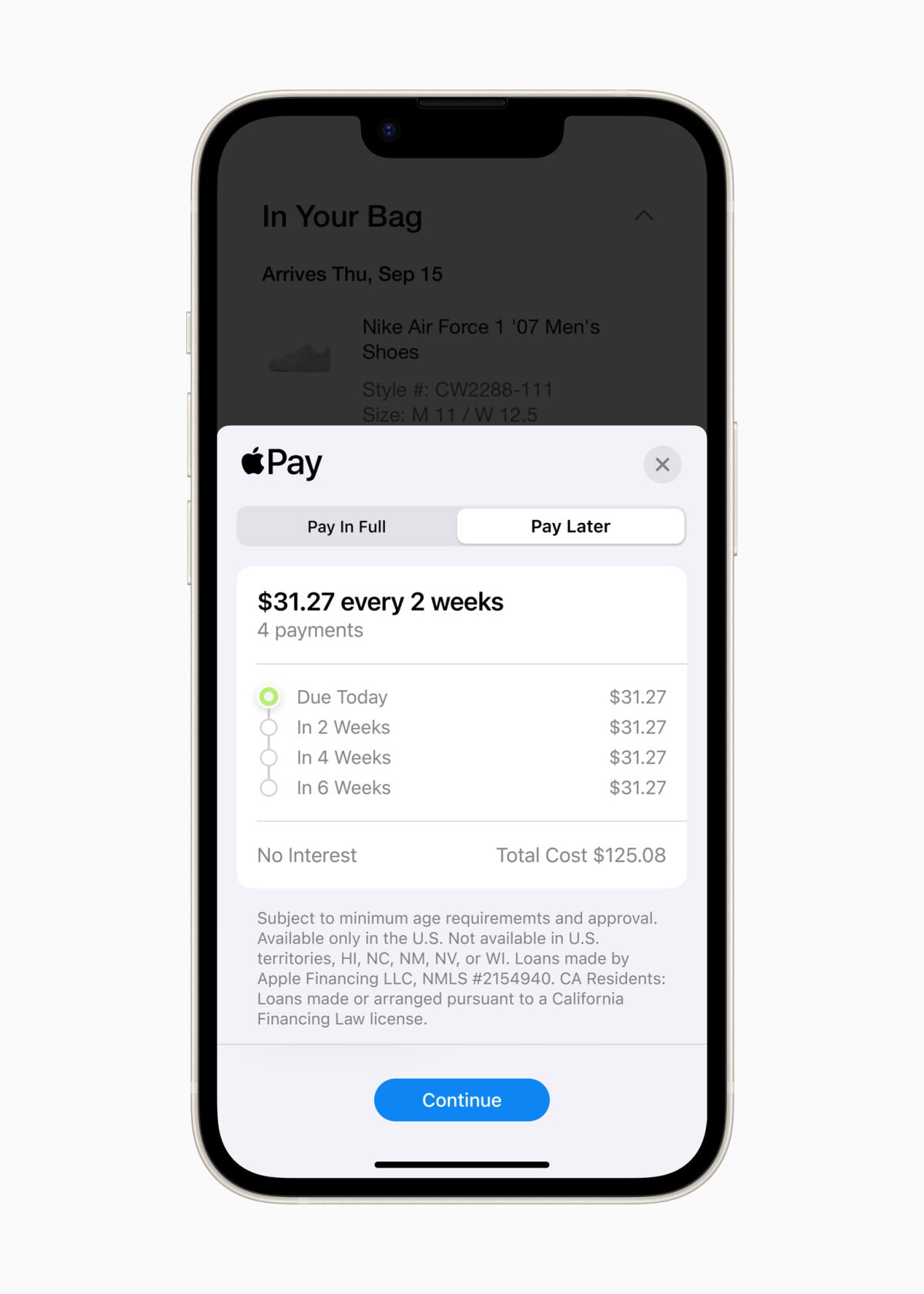

“Buy now, pay later” loans, also known as point-of-sale financing, typically appear as an option at online checkout. You’re presented with the option to pay in full, or to split your purchase into installments with zero interest. A marketing professor told the Atlantic that in her consumer polling, shoppers said using a credit card makes them feel guilty, but they made no moral distinction between using BNPL and swiping their debit card for the full amount.

Apple’s announcement of the service touted its benefits: “Apple Pay Later was designed with our users’ financial health in mind, so it has no fees and no interest, and can be used and managed within Wallet, making it easier for consumers to make informed and responsible borrowing decisions.”

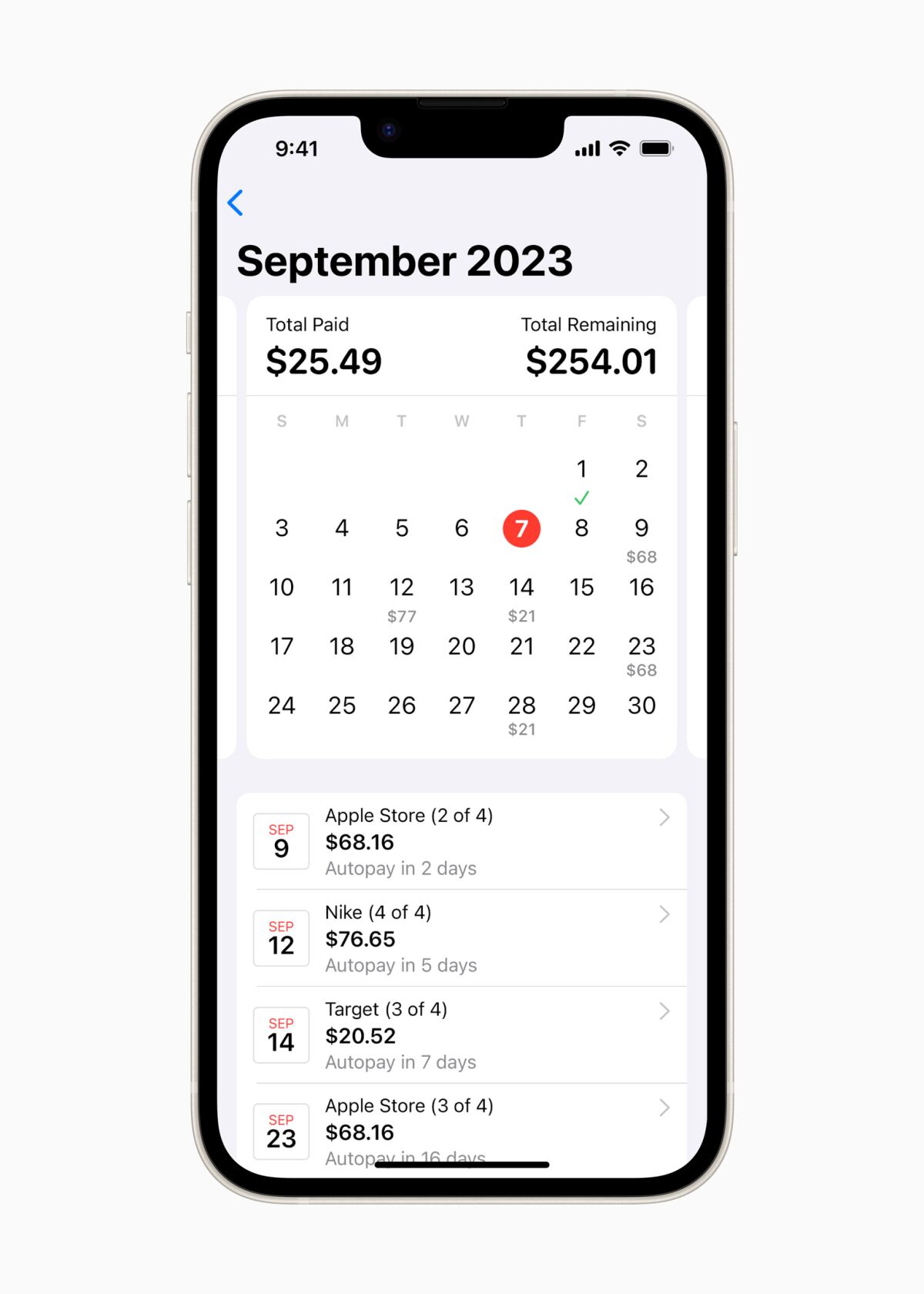

And it does appear to have some benefits over competitors: Apple showed off a slick interface that lets users manage their loans and view a calendar of upcoming payments. Borrowers have to link a debit card to make repayments, so they can’t get further into debt by paying off one loan with another (e.g., a credit card), a criticism the industry has faced. Loan recipients will get notifications about upcoming payments, so there’s less chance of being caught off guard when payments go through. And the company says it plans to start reporting Apple Pay Later loans to U.S. credit bureaus starting this fall, which could help borrowers build credit through on-time payments.

Like every other lender in the BNPL space, Apple Pay Later loans are spread out in four installments. That number isn’t a coincidence, said Tom Y. Chang, an associate professor of finance and business economics at the USC Marshall School of Business.

“It’s all to avoid the Truth in Lending Act,” he said. “The Truth in Lending Act kicks in at five installments. So they all put it just below the threshold.”

The Truth in Lending Act is a federal law that dictates how lenders have to treat customers, including making it easy to understand all the potential fees and interest charges on a loan. If you aren’t subject to it, you can sell people on all the upsides of your loan without having to bum them out with the downsides.

An image showing what Apple says the calendar view of Apple Pay Later will look like on an iPhone.

(Apple)

Allow us to bum you out with the downsides.

A report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that compared with someone who didn’t use BNPL financing, the average BNPL borrower was more likely to have a lot of debt, more likely to have delinquencies on their credit report, more likely to carry a balance on their credit cards, and more likely to use payday loans, pawn shops and account overdrafts. The bureau said the idea that BNPL extends lines of credit to people who don’t otherwise have that option is false: “In fact, they were more likely to borrow using credit and retail cards, personal loans, student debt, and auto loans compared to non-BNPL borrowers.”

There are other potential downsides, including how BNPL uses consumer psychology to affect your decision-making.

When you buy something, you face what’s known as “friction” in the shopping experience — all the points in the process that make you think, “Do I really want to complete this transaction?”

Vendors want to reduce that friction as much as possible.

Online shopping — now available 24/7 on the supercomputer that lives in everyone’s pocket — reduced the friction of getting to the store.

When the customer comes up to the register and has to pull out their wallet, they face another friction point. Greg Ward, a certified financial planner and the think tank director at financial coaching company Financial Finesse, said the lending industry is always looking for ways to alleviate the so-called pain of paying.

“Making it easy, ‘making it fun and making it cool, that’s been the game of the credit card industry since the ‘60s,” he said.

Think of how much more likely you are to buy something from an app or online store that already has your credit card number saved. That’s a friction reducer. Still, you have to confront the checkout screen, with that looming total staring back at you. If you got a pop-up message that said, “Want to open a new credit card to pay for this?” you’d probably say no. But when you get a pop-up that splits that total purchase price into four with an instant loan, you might find yourself able to justify it.

Perez said in her experience, vendors make using BNPL easy to the point that it seems some retailers are pushing the service: “Like, ‘Are you sure you don’t want to AfterPay?’ I think it’s pretty nefarious.”

The BNPL model doesn’t charge customers interest or fees up front. Lenders instead make money by charging the vendor four payment processing fees instead of one. That can drive up prices for everyone, including non-BNPL shoppers. Another way businesses benefit: It could encourage customers to spend more. The owner of a restaurant in Malibu told the New York Times that customers who used BNPL for their purchase spent 40% more than other people placing an online order and twice as much as people ordering in person.

Are there any more potential downsides to using BNPL? Yes.

- The idea that the loan is “no interest, no fees” is true only to an extent. If you don’t pay the loan back on time, you could be subject to all sorts of fees — which, again, the lender doesn’t have to tell you up front, because they aren’t subject to the Truth in Lending Act. For instance, AfterPay says a late payment could result in a fee of up to $68.

- Apple lets you see all of your Pay Later loans in one convenient calendar. But if you’ve also got loans through Affirm, Klarna or other lenders, it can get tricky to keep track of all the upcoming payments and due dates in your budget. (You have a budget, right?)

- Though a soft credit pull doesn’t ding your score, it still shows up on your credit report and could affect your ability to get other sources of credit or loans. For instance, a mortgage lender could legally look at a soft credit check for a microloan in a food delivery app — an increasingly widespread behavior — and question whether you can afford a mortgage when you need to split up a sandwich across a few paychecks.

- Apple says it plans to report Pay Later loans to U.S. credit bureaus starting this fall, so on-time payments could boost your credit score — but that takes away from the idea that this type of debt somehow exists outside of your credit report. The three major credit bureaus have all announced plans to include BNPL loans on credit reports. Late payments reported to the credit bureaus can definitely hurt your credit score.

- Paying off a loan over six weeks means assuming your paychecks will be the same six weeks from now. In the best of times, you can’t know the future; right now, with layoffs looming in many industries and COVID still a thing, it’s hard to guarantee those installment payments on your new blender will feel as fiscally palatable in six weeks.

So what are the upsides, beyond the zing of instant gratification? In some cases, it may be better than the alternative, Ward said: If you’re using BNPL instead of turning to something like a payday lender or a pawn shop, or a high-interest credit card you don’t pay off every month, it could be the right move.

Think of BNPL as “kind of a ‘break glass in case of emergency’” alternative to those types of high-interest debt, he said, “instead of it becoming the routine.”

What Apple says the Apple Pay Later checkout screen will look like on an iPhone.

(Apple)

There’s nothing explicitly wrong with Apple Pay Later compared with other BNPL lenders. If you must take on debt to make a purchase and you are confident you’ll be able to afford what you bought when the payments are due, Apple Pay Later seems to offer some slight advantages over competitors, including an easier way to keep track of payments and, in the future, possibly helping build your credit.

Perez said if using BNPL is the difference between keeping the lights on or feeding your kids, “at least it’s being utilized in a way that’s productive. Better than going into debt for jewelry and clothes.”

But in most cases, a traditional credit card is better, Chang said: “If you have a credit card, I don’t see why you would ever use this.”

There are actually quite a few advantages to using a credit card for your transaction instead of BNPL, he said. If you have a credit card that you pay off in full every month, you have basically the same amount of time to pay off your purchase as you do with BNPL — around four to six weeks, depending on where you are in your billing cycle. A credit card offers rewards or points. And you are more protected if you need to dispute the charge or get a refund.

If you do use BNPL to fund something that might be described more as a “want” than a “need,” it doesn’t mean you’re doomed to debt. Keep track of what you owe, make your payments on time, and don’t fall into the habit of borrowing money to spend money. Using BNPL isn’t the end of the world. It’s just not the smartest financial move.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Matt Ballinger, Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Automobiles News Click Here