A couple of years ago, Laurence des Cars was named the head of Louvre. The importance sinks in when you realise it is the first time ever in the Parisian museum’s 230-year-history that a woman sits at the top. The same year, Rijksmuseum featured women artists in its ‘Gallery of Honour’ — the first time in its over two centuries of history.

The numbers in the art world are not stacked in favour of women. For instance, in the last 15 years, women artists took only 3.3% of global auction sales, according to the 2022 Burns Halperin report, while a 2018 analysis showed that there were no women in the top 0.03% of the auction market, where 41% of the profits are. Burns Halperin also states that museum acquisition of works by female artists in the U.S. has declined to 11%. Why does it matter? Unlike hosting a rotation of exhibitions, only art that’s acquired is deemed important enough to conserve.

Representation may be getting a fillip of late — women outnumbered male artists in the main halls of the Venice Biennale — but is it enough? “Representation is not about visibility because very often it is tokenism. While we are celebrating the Venice Biennale, it’s one biennale out of so many and the first that’s attempted to redress the balance. Do you think the next one is going to do that?” asks Shubigi Rao, curator of the ongoing Kochi-Muziris Biennale, which has a strong female contingent.

Curator Shubigi Rao.

“I think it is really important for younger, aspiring women artists to see older women who make incredibly rich, in-depth, and thoughtful work. Like Devi Seetharam, who speaks about the patriarchal structure in Kerala and how men occupy and enforce their ownership of space, private and domestic. Or works such as Cecilia Vicuña’s that delve into memory, language, decolonisation and indigenous history; and Gabrielle Goliath’s, which is about femicide in South Africa.”

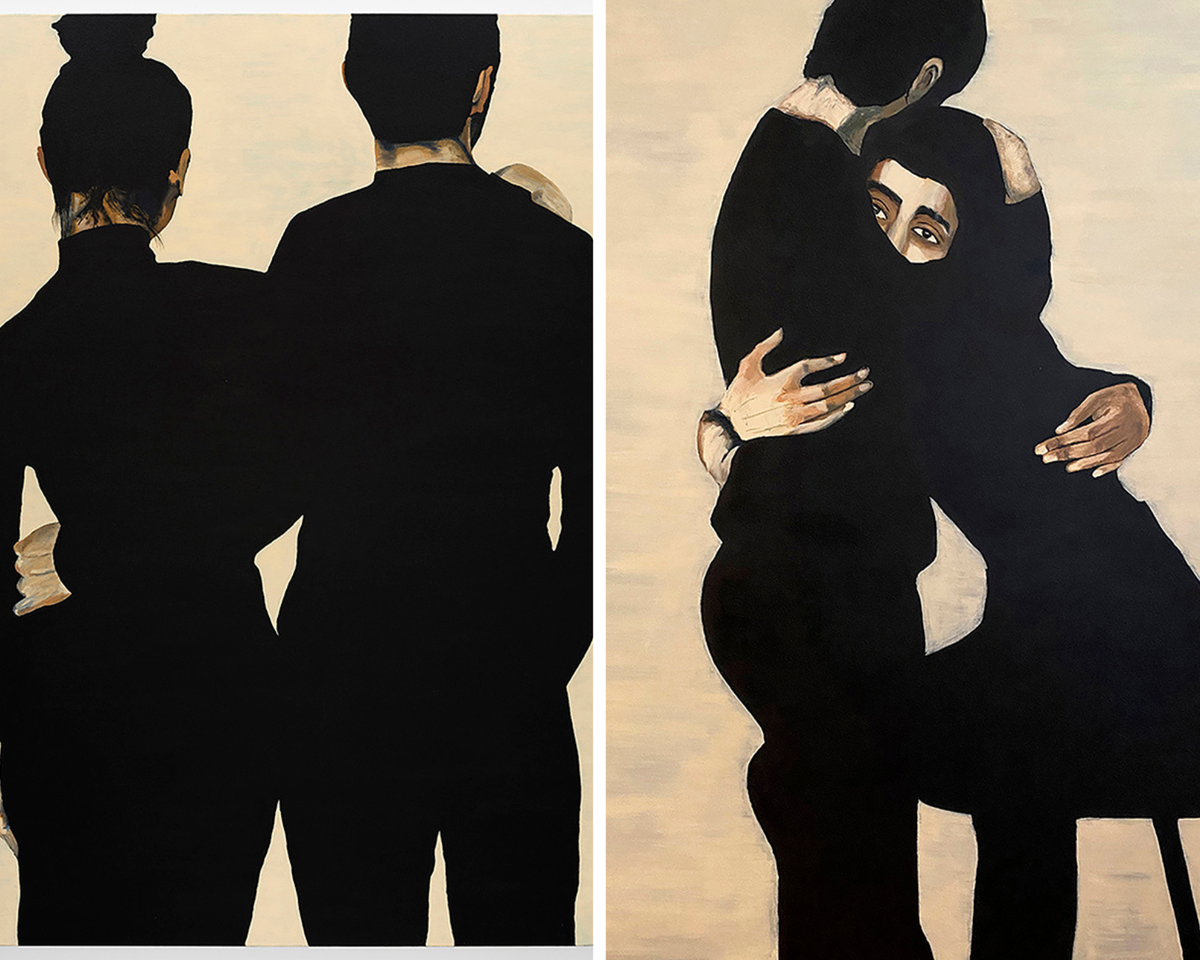

The role of artists as chroniclers has been particularly important in these recent times of war, protests, and pandemics. They’ve created works that speak to trauma, suffering, hope, and empathy, becoming the voices of people showing courage in the face of oppression. Several Indian artists, especially women, have emerged at the forefront of this confrontation of the legacies of exclusion — openly telling their own stories, including issues such as miscarriage, Partition, and climate change.

As Priya Khanchandani, head of curatorial at The Design Museum in London, says, “We have a long way to go, but there are more opportunities than before for a positive change, and untold stories to tell, which makes the arts sector a dynamic place to be in right now.”

Six women artists discuss their canvas, voice and worldview.

Shilo Shiv Suleman

Shilo Shiv Suleman, Bengaluru

The visual artist is consistently in the foreground of intertwining South Asian goddess culture with technology and social justice. Her work covers illustrations, poetry, street art, NFTs, and installation art. Last November, at the COP27 climate summit in Egypt, Suleman painted a mural called Fearless, of three female climate activists standing up to industrial players who are decimating the Global South. When I spoke with her, she was doing a similar piece in Sri Lanka — working with fisherwomen who are suffering from the economic crisis and how the construction of the Colombo Port City has shifted the way that indigenous fisherfolk have access to the water. “The work of Fearless,” she states on Instagram, “is to turn up in moments of fear and make space for love, beauty and imagination.”

Voice and worldview: Suleman started painting at the age of 13. “I see art as the ultimate alchemy. It has the ability to heal and transmute so much,” she says, explaining that it’s the foundation of the work she does with the Fearless collective, the initiative she started in 2012 that creates public art interventions with women and misrepresented communities across the world — “where art and storytelling serve as a form of healing”. She says she’s seen everything “from policemen embracing protesters after seeing our murals, to death threats turning into dance parties in Beirut where local Armenians understood what Syrians were going through after our workshops”.

Necessary narratives: She feels the ones that need to be highlighted are those of people who don’t have the ability to tell their stories or have had the same story told repeatedly. “In India, for example, when we read about the Dalit community, we only hear about oppression, death, and rape. While it’s important for us to recognise that these brutalities exist, we also need to affirm what life and livelihood for these communities look like,” says Suleman. “These are the voices, especially those of the women from those communities, that need to be brought out.”

Maya Varadaraj

Maya Varadaraj, New York

The interdisciplinary artist’s works revolve around the stories and experiences of South Asian women and the diaspora. Her paintings and installations, which draw inspiration from a multiplicity of cultures, have included themes like rape, domestic violence (portrayed through glass bangles), and the role of women — within their families, as concubines, as objects of desire, etc. She has looked at her own miscarriages and the way women are encouraged not to speak about their bodies in one of her recent works.

The big influences: “My work has gone from being macro to micro,” she says, “from just making a social commentary to looking more personally and then societally. I’ve been thinking about my own circumstances as a South Asian woman, the cultures, the biologies and all that defines being that. And there’s a duality and complexity of having been brought up in India and being educated and living in the United States that I’m trying to parse.”

What changed after the pandemic? While earlier Varadaraj looked at South Asian women in general, and their triumphs and tribulations, she is now starting to take herself into account.

“There have been experiences that I’ve had in the past three years, my own personal journey with trying to get pregnant, and having miscarriages that I feel are specific to being a woman,” she says. “I had never heard of anyone in my immediate family having miscarriages. So, I wondered how is it that 40% of women have miscarriages and I still feel so alone.”

Perhaps women don’t talk about it because it is so traumatic and the language around it implies culpability. “The fact that it is called a miscarriage makes me feel like I did something wrong; almost like I mistakenly dropped something. I felt that since I make work about the complexities of being a South Asian woman, I need to share my own experience so that someone else can take comfort in it.” Varadaraj will be continuing her work on this theme in 2023.

Avani Rai

Avani Rai, Mumbai

One of the photographer’s most talked about works in recent times is a photo series that throws a spotlight on the trauma that women and children face in the conflict zones of Kashmir. Their everyday struggle, often overshadowed by the more sensational ones of violence, gain a voice in Rai’s stunning black-and-white photos.

The photographer admits that she didn’t have a strategy when she started photographing the women; she was simply responding to what was in front of her. “I was not a photographer then,” she says. In 2017, her work for a documentary about her father, Raghu Rai: An Unframed Portrait, had her travelling to Kashmir. “It made me experience so many stories that I just couldn’t resist picking up the camera and photographing whatever came in front of me.” These include hard-hitting photos taken during the unrest that followed the Indian army’s killing of the militant group Hizbul Mujahideen’s commander.

Avani’s social media brims with photos that stem from the same deep desire to express her experiences, unedited. “It gets people to see what you believe in or how you look at the world,” she says. And that’s important: “Women look at the world in a certain way that men can’t, and the other way round. It’s a point of view, and it should be dignified.” She’s carried that narrative into her films, like Two Sisters And A Husband (2022), in which she acted. Directed by Shlok Sharma, the drama about ‘a family gone wrong’ premiered at the Tribeca Festival.

For Rai, the world is always in a flux. She remains untethered to the ideas of a good or bad time. “I feel that everything is an opportunity and everything can also be a deterrent.” She doesn’t believe in being married to a singular narrative. “Every moment the world changes, and you respond differently. I feel like that’s evolution.”

Vibha Galhotra

Vibha Galhotra, Delhi

The multimedia artist engages with questions: that interrogate society’s structures — social, economic, and political; of current educational systems that prioritise teaching that meets commercial demands; or the implications of human activity on the environment. Galhotra’s works, which include installations, videos, public art interventions and photography, are profound and darkly funny, using objects like ghungroos to create sculptures, or films to comment on the self-destructiveness of consumerism.

“I see my art as an evolution of self into an aware being, and not separate from my life,” says the artist, who has been awarded the Jerusalem International Fellows, and Rockefeller Grant, among others. “I call myself an eco-artist whose concerns are community-based rather than self.”

Pandemic work: Art, she says, gives her the power to ask simple questions. Last year, Galhotra lived in Israel for two-and-a-half months. “I lived with both Palestinians and Israelis, and realised that the division is politically driven. It has nothing to do with the people, who are humble and beautiful.” Her response to this was to build a wooden temple in Jerusalem that’s shared by three religions. Its stone altar, with an audio recorder embedded in it, emits songs, chants and hymns ( Mountain to the Sea, on a 45-minute loop) sung by religious leaders and teachers.

Encouraging debate: Galhotra believes in creating her own power within her community and making the community stronger. In her solo show at Nature Morte, Silent Seasons (which ends today), she draws inspiration from the prophetic work of American marine biologist Rachel Carson, to “cast herself as an observer and narrator of a future fiction of apocalyptic situations”. To show ‘promises and unpromises’. “Rachel Carson wrote [the book] Silent Spring in the 1960s. So, she’d already made us aware that the chemicals we are using will lead to health issues. It’s all political and capital driven. So, we need to understand our world and generate awareness amongst communities about what is going to happen.”

Pritika Chowdhry

Pritika Chowdhry, Chicago

The artist-educator-activist’s practice, which includes large-scale sculptures and site-sensitive installations, catalogues the violence of imperialism alongside global acts of resistance. For over a decade she has created around military and civil conflicts, especially the Partition. In December, her solo retrospective, Unbearable Memories, Unspeakable Histories on the Partitions (at the South Asia Institute of Chicago) incorporated mixed-media works ranging from latex casts of monuments and weapons, to poetic recreations of sites where acts of brutality took place.

Chowdhry calls her work anti-memorials — “objects that do not simplify world events or the lives of the people most affected, but instead concretize their memory. They are meant to draw attention to the forgotten and the unreported, like the women abducted during the Partition but whose experiences are often excluded from discussions of Partition’s impact”, she says, adding that she is creating an online Partition Museum that will launch later this year.

Changing narratives: “It’s been 15 years since I started looking at these horrific subjects,” says Chowdhry, who will be joining the National Indo-American Museum this year as a curatorial consultant to help create a permanent exhibition about the history of migration from South Asia to America. “The one change that made me optimistic during COVID-19 was seeing a lot more creation from women, especially those narrating their own stories.” That there are so many more female artists in India, from Bharti Kher to Shilpa Gupta, who centre women’s perspectives in their work is probably the biggest gain of the past few years. “But we need to have more conversations [about topics such as the very high occurrence of rape and sexual violence]. Because a conversation is the first step towards realising that something’s wrong and vocalising it.”

Akshita Gandhi

Akshita Gandhi, Mumbai

The photographer and multimedia artist uses paints, embroidery, and collages on photos to look at dichotomies such as construction/deconstruction. She often uses urban landscapes and heritage architecture in her pieces, like in her 2022 solo exhibition, A love letter to my home — which focused on freedom and independence through India’s post colonial identity. But some time ago, she created Freedom – I read Banned Books. The series, which was exhibited in New York and Miami, tackled patriarchy. “It not only spoke about freedom, about breaking out of stereotypical images of gender roles and biases, but also about the taboos that stop women from embracing their sexuality.”

Pandemic and art: While Gandhi photographs the same structures, cityscapes, and landscapes today, she feels she now brings a lot of the emotions that she experienced during the lockdowns into work. “I started to use a lot of colours and design, a lot of motifs and elements of fantasy and escapism, because I realised that’s all we had,” says the artist, who is currently concentrating on her textile works, working with a team of karigars who lost their jobs during the pandemic.

Priya Khanchandani

| Photo Credit:

Suzanne Zhang

Priya Khanchandani, London

Head of Curatorial, The Design Museum

A little over a year ago, The Design Museum showed Amy: Beyond the Stage, its first exhibition dedicated to a single musical artist. With memorabilia from the stage and ordinary life, such as beloved guitars and frocks, to heavily-doodled A4 notebooks and shopping lists that included Chanel No.5, it provided an ‘intimate connection’ to the late English singer-songwriter. “The show was significant partly because Amy [Winehouse] is such an influential figure in music culture, and also in terms of her style and the legacy of that,” says Kanchandani, who was, incidentally, born in the same year as the singer. So, in many ways, looking back at her contemporary was a wonderful experience.

Amy: Beyond the Stage at The Design Museum.

Interdisciplinary interests: As a curator, Khanchandani believes she is a storyteller. “Your job is to find a story and to be able to communicate that to audiences in a way that’s interesting to them.” While she doesn’t believe that her influences are necessarily different because she is a woman, she does ensure representation in her work. “There is a sea change in how women’s narratives are being presented now. Women were historically maligned from the canon of design and architecture. That is now being redressed. And, of course, we are going through a different kind of sea change in the wake of Black Lives Matter, which has created a second wave in shifting narratives.”

In the context of her work, just in the last couple of years alone she curated a solo show on French architect and designer Charlotte Perriand, a display about London-based designer Bethany Williams, besides the Amy Winehouse exhibition.

A display from London-based designer Bethany Williams’s exhibition.

A diasporic lens: As a child of Indian immigrant parents, Khanchandani says she grew up in a very different context to most people that she works with. And some of her biggest challenges have been navigating the structures “that you work in as a woman, as a woman of colour, as a person who grew up in a working class town who went to a comprehensive school”. Traversing that, and finding space for her views and her perspectives to have a voice, has been a journey over the last 10 years. “I feel like I’m starting to be able to do that through some of the work that I have coming up.”

A display from artist Yinka Ilori’s exhibition

| Photo Credit:

Nick Rees

For instance, a display by artist/designer Yinka Ilori (on till June 2023), who fuses his Nigerian aesthetic with a contemporary, colourful and fun version of postmodernism. “It’s about the creation of a kind of diaspora visual language. It’s one project where I’ve been able to bring in my perspective as someone who is of diasporic origin. I understand his work professionally and from a personal perspective, as someone of dual heritage.” Another curation to look forward to: The Offbeat Sari, which will explore the radical reinvention of the garment, demonstrating “the sari to be a metaphor for the layered and complex definitions of India today”.

Challenges of an overstimulated world

“We live in a world of too much ‘content’. It is a word that I abhor because content is not curated; it is the opposite of curated,” says Khanchandani. But our overstimulated world is not a challenge to a curator. “If anything, I think it’s a dream because there’s so much more information and potential archives available to you. And I think today, more than ever, people want access to ideas that are carefully considered. The museum offers a way of accessing this: ideas that are grounded in knowledge, and that holds a degree of authority. In a world where there is so much information that is untrustworthy, people increasingly crave the kind of experience offered by curators in museums. Otherwise, why would everyone be calling themselves curators in every context!”

The writer is the author of a fantasy series, and an expert on South Asian art and culture.

With inputs from Surya Praphulla Kumar and Naveena Vijayan

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here