Machines are helping rewrite history, peering into the ancient past with greater accuracy. There are robots exploring sea beds in search of lost cities, light-detection radar creating maps of ruins hidden beneath forests, and 3D modelling techniques helping conserve ancient temples.

Researchers in Egypt used non-invasive computed tomography or CT scans to virtually “unwrap” the mummy of King Amenhotep I (c 1525-1504 BCE) in December 2021, visualise his face, study the method of mummification, and estimate his age at death (they believe he was 35). In Texas, researchers from Southern Methodist University used portable 3D laser technology to electronically preserve a rare fossilised dinosaur footprint from 110 million years ago.

Meanwhile, remains of ancient protein-rich laddoos were identified at a Harappan-era site in Rajasthan, in June 2021. Researchers from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow, and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for a chemical analysis of ancient food particles and found that, yes, Indians have been eating cereal-based laddoos for over 4,000 years.

Over the past decade, ASI has relied heavily on technology for a more detailed look at Harappan-era ruins at Rakhigarhi in Haryana and Sanauli in Uttar Pradesh, says joint director-general Sanjay Manjul. “We’ve used aerial photogrammetry, x-ray spectrometers and ground penetrating radar to find chariots and swords from 4,000 years ago,” he says.

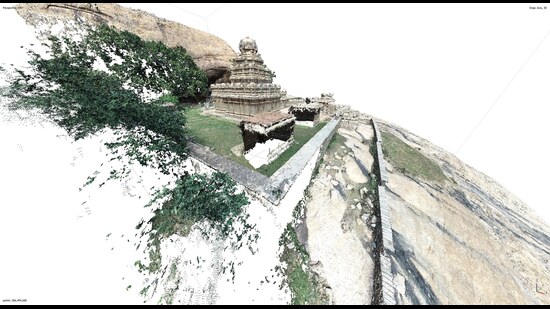

Elsewhere, 3D photogrammetry and a robotic arm was used to piece together a panel of 7,000 pieces during the excavation of Karnataka’s Kanaganahalli Stupa in 2013 (a similar effort is now being used to create a copy of Parthenon sculptures at the British Museum).

3D photogrammetry involves recording images of an object from various angles to process them into 3D models. “We had to piece together 7,000 fragments of stone from the 3rd century BCE, which were discovered scattered at the site,” says Kailasa Rao professor of architectural conservation at the School of Planning and Architecture, Vijayawada, and member of the union government’s National Monuments Authority (NMA). “So we used 3D photogrammetry to reimagine the panel and a milling robot to reconstruct it.”

In the field of heritage-monument conservation, digital crack meters now offer readings accurate to a hundredth of a millimetre. Arun Menon, associate professor of structural engineering at IIT-Madras, has worked to install digital data loggers and vibration sensors at heritage sites like Ripon Building in Tamil Nadu and Odisha’s Shree Jagannath Temple.

As is often the case in India, the best tech isn’t widespread enough. “We do not have enough investment in instrumentation and technology, and general scientific literacy for archaeologists,” says Mayank Vahia, retired professor at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, who helped set up the country’s second carbon-dating facility at the University of Mumbai. “India has two such machines, China has nine. We need at least half a dozen more of these to be able to level up in our attempts at understanding the past.”

The lack of skilled human intervention remains one of our biggest drawbacks, adds Vinod Daniel, museologist and member of the Board of the International Council of Museums (ICOM). “We need people trained in specific skills in sectors such as conservation, documentation, interpretation, exhibition development. We might have about 400 skilled conservators in the country now; what we need is ten times the number.”

Discovery: Scans that bring cities, gardens to life

Could there be an ancient city lurking beneath the Amazon rainforest? A study published in May reveals what the mysterious mounds beneath the thick vegetation in the region of Casarabe, Bolivia, might be. Researchers from the German Archaeological Institute estimate that the mounds are pyramids and stepped platforms belonging to the Casarabe culture settlements from about 1,500 years ago.

The mounds rise up to 22 m and seem connected to ruins of canals and reservoirs, graves, and an elevated roadway. The researchers would never have known of the settlement if not for LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), invented in 1961 to help satellites map the earth using light beams. In Bolivia, a laser scanner mounted on a helicopter sent pulses of beams to create a 3D map of the site beneath the dense tropical forest.

“Our results indicate that the Casarabe-culture settlement pattern represents a type of tropical low-density urbanism that has not previously been described in Amazonia,” states the study report published in the journal Nature.

Closer home, aerial photogrammetry and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) has helped the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) make some startling discoveries at the Harappan-era sites of Sinauli in Uttar Pradesh and Rakhigarhi in Haryana. “What looked like a chunk of mud to the naked eye, with a copper inlay and iron nails, turned out to be the remains of decomposed wooden chariot wheel, after we used X-ray imaging,” says ASI joint director-general Sanjay Manjul, who led the project from 2018 to 2021. Other discoveries included a horse-driven chariot, wooden coffins, swords, ivory combs and prominent graves, likely of people at the top of the social hierarchy.

The combination of laser scanning and GPR also helped ASI spot the lost Mehtab Bagh (Urdu for moonlit garden), a royal park within the Red Fort premises, in 2006. “The 1850 layout plan of the Red Fort mentioned two gardens. While Hayat Baksh remained, there was no trace of Mehtab Bagh,” says ASI spokesperson Vasant Swarnkar. The garden had been flattened by the British, turned into a parade ground and barracks built around it, Swarnkar says. “Not only did we find the exact location of the garden that was once the late-evening leisure space for the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s family, in 2013 we also excavated the water channels and fountains.”

Decoding: Early ironwork, man’s history with fire

From the tomb of Tutankhamun, which was broken open a century ago, to humans’ early relationship with fire, new technology is peeling back the layers to tell us more.

An iron dagger taken from Tutankhamun’s tomb, for instance, has revealed the secret to prehistoric smelting. The dagger was among 5,000 artefacts taken from the Egyptian pharaoh’s tomb in the 1920s, all dating to about 1300 BCE. With no evidence of iron smelting until the 6th century BCE, researchers couldn’t fathom how it was made.

In 2016, Italian researchers used x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) to examine its elemental composition, and discovered that the dagger contained unusually high levels of nickel. This suggested that it was crafted from the remains of a meteorite. Researchers at the Chiba Institute of Technology in Japan then used XRF to re-examine the dagger and their study, published in February, outlines how the distribution of nickel content allowed the iron to be forged at a relatively low temperature. In an aside, the researchers also found out that lime plaster was used to embed gemstones in the hilt, a process followed in Mitanni and not Egypt, which suggests the dagger may have been a wedding gift from the neighbouring king.

Meanwhile, scientists from the University of Toronto, Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have been using artificial intelligence (AI) and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to try and trace the earliest known evidence of the controlled use of fire.

FTIR spectroscopy measures how different wavelengths of light are absorbed or reflected by a surface, to estimate what organic substances it might contain. The researchers used it to study flint tools excavated from archaeological sites dating to at least 800,000 years ago in Israel. The aim was to find out if the tools had been burned.

The study, published in June, explains how an AI program confirmed that the tools were exposed to temperatures of up to 600 degrees Celsius, suggesting that this could be one of the earliest known cooking sites. “Especially in the case of early fire, if we use this method at archaeological sites that are one or two million years old, we might learn something new,” co-author of the paper Zane Stepka said, in a statement released by the Weizmann Institute.

In Italy, traces from inside large ceramic jars or amphorae were analysed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS; which identifies and separates chemical markers), to determine that ancient Romans drank both red and white wine, made from locally grown grapes, in the 1st century and 2nd centuries BCE. The team of scientists from France and Italy even identified traces of ancient pollen from local grapevines.

In India, Nikhil Ramesh, conservator in charge of documentation, education, and research at Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS; it has a cutting-edge conservation lab), has been using XRF and FTIR to study artefacts in the museum’s collection. In 2016, these technologies unlocked the secret to a dark overcoat on a bronze incense burner from the Meiji period in late-19th-century Japan. “We knew the motifs on the burner were gilded in gold and silver. We couldn’t figure out what the overcoat was. FTIR helped us understand its molecular composition so that we could use a solvent to remove it and reveal the intricate gilding,” Ramesh says.

Preservation: Recreating history in 3D

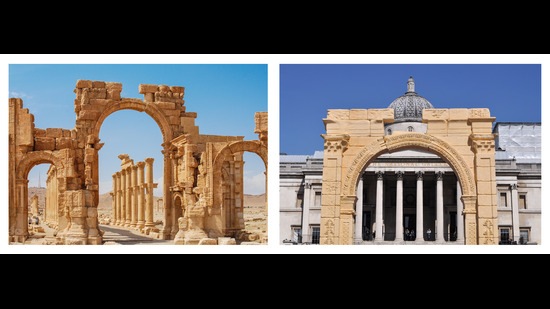

In London, new-generation sculpting robots and 3D-printing devices are helping create faithful reproductions of artefacts. In 2016, Oxford’s Institute for Digital Archaeology used a 3D printing device to recreate Syria’s 2,000 year-old Roman Monumental Arch of Palmyra, which was destroyed by ISIS in 2015. The two-thirds scale model, was unveiled at Trafalgar Square in London for three days, before it travelled around the world.

This year, the department is using a milling robot that sculpts and processes marble to copy two Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum: a life-sized head of a horse and a panel depicting the battle between the Lapiths and Centaurs. The models will be displayed by the end of July.

In war-ravaged Ukraine, citizen conservationists are using their iPhones in an effort to conserve local heritage. As a part of an initiative called Backup Ukraine, launched in April by the heritage conservation network Blue Shield Denmark and Danish National Commission for UNESCO, anyone can digitally archive monuments, landmarks, cultural sites and artefacts using a 3D scanning application called PolyCam. Uploads so far include public landmarks such as churches and local street art. The Back Up Ukraine team says it hopes to eventually create 3D models of destroyed artefacts and architecture using this footage.

Closer to home, Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) is in the process of installing new-generation sensors to remotely monitor ancient artefacts in its collection. The wireless data loggers will track changes in temperature,relative humidity and pressure levels. “A drop in atmospheric pressure can signal the onset of rains and a rise in humidity levels can cause microbial growth on delicate documents and ancient art,” says Nikhil Ramesh, conservator in charge of documentation, education, and research. “The idea is to ensure we are now one step ahead. We hope to be able to take corrective action as needed.”

We still have a lot of catching up to do. Arun Menon at IIT-Madras, has been working on several government projects to monitor the health of heritage structures. “We have immense potential but are possibly behind Europe by 20 years, in the uptake of technology to monitor and preserve our past,” he says. A prime example, he adds, is Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa. It’s lean was rectified from 5.5 degrees to less than 4 degrees over 20 years. “After constant health monitoring and scientific restoration it is in better structural health now.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here