This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Don’t be fooled by the unsettling elegance of the phrase toilet plume. It describes the invisible cloud of particles heaved by a toilet when flushed, and was once feared to be a vector for COVID-19. My colleague Jacob Stern recently revisited the toilet-plume panic for The Atlantic, writing that although this early-pandemic fear hasn’t been substantiated, there are still other reasons to beware of the open lid. I called him to find out more.

But first, here are three new stories from The Atlantic.

Beware the Plume

Kelli María Korducki: You write that toilet plume has been a subject of scientific inquiry for quite some time. How did COVID enter that conversation, and when did it leave that conversation?

Jacob Stern: I’m not totally sure what the initial spark for it was. But as you say, people have been thinking about toilet plume for a shockingly long time. The earliest papers go all the way back to the 1950s. There’s also a history that I didn’t even get into in this article, of toilet-related public-health panics—many of them completely unjustified—having to do with either the civil-rights movement or the AIDS epidemic. And so, in some sense, it was deeply unsurprising that in this moment of fear and uncertainty, there would be a toilet-related panic around the coronavirus.

Kelli: I remember that panic. I had a friend who was convinced she was going to get COVID after an upstairs neighbor’s toilet overflowed, sometime in that scary first year of the pandemic. What do you think set off worries like this one?

Jacob: If you go back and look at when the big news articles about toilet plume were published, those were back in June 2020. There was a study published around that time, which I think was one of the instigators for this whole panic suggesting that toilets might be, as one of the newspapers put it, flinging coronavirus all over the place. And then there were another couple of waves of panic.

In my article, I mention a review paper from December 2021 [which found “no documented evidence” of viral transmission via fecal matter] that kind of dispelled the myth. But plenty of academic papers aren’t particularly noticed by the public. So I don’t think that, in the public imagination, that paper made all that big a dent.

Kelli: You point out in your article that even though the potential COVID connection was overblown, we should still be a little afraid of toilets.

Jacob: The basic takeaway is that even if it seems like toilets are not a vector of COVID transmission, there are still all sorts of other pathogens that are really unpleasant to have to deal with. In the case of toilet plume, gastrointestinal viruses such as norovirus are the main worry. And those, we know, are transmitted via what are called fecal-oral routes. Those are still a concern, as far as toilet plume goes. If you don’t want a stomach bug, it’s still worth worrying about.

Kelli: This may be too much information, but although I’ve read your article, I’m still kind of convinced that I caught COVID last year from a public bathroom. I can’t think of any other possible exposures in the infection time frame. Is my position defensible?

Jacob: I would say your position is defensible, yes. Despite the fact that it seems like toilet plume itself was not a huge driver of COVID transmission, there are obviously lots of other human beings in public bathrooms, all of whom are quite capable of transmitting COVID via respiratory pathways. So it seems totally plausible that you might have gotten COVID in the normal way, from someone else’s breath, and that just happened in the public restroom.

Kelli: Has your writing and reporting on this subject changed your behaviors around flushing?

Jacob: Yes, for sure. Even before I started reporting this story, the toilet-plume discourse had penetrated enough that I was already much more careful about always closing the lid on a toilet than I had been previously. Now I not only do that myself but get annoyed at family members and friends when they fail to do so. I’ve become pretty self-righteous about it.

I will also say that, when I have one on me, I will now wear a mask in a public restroom, which is certainly not something I would’ve especially gone out of my way to do before. After writing this story, putting on a mask for the three minutes I’m in a restroom—even if I’m not wearing one otherwise—seems like a great move rather than a pointless one.

Related:

Today’s News

- The World Health Organization warned of a “secondary disaster” for survivors of the devastating earthquake in Turkey and Syria in the face of forecasted snow and cold-weather conditions, in addition to a lack of power, water, and communications.

- The State Department announced that the Chinese spy balloon shot down by the U.S. military last weekend was capable of collecting electronic-communication signals.

- A Southwest Airlines executive testified at a congressional hearing about the airline’s holiday crisis, in which thousands of flights were canceled.

Evening Read

‘Scar Girl’ Is a Sign That the Internet Is Broken

By Caroline Mimbs Nyce

The scar first appears on Annie Bonelli’s TikTok on March 18, 2021. In the video, she is in a car, earbuds in, lip-synching to the song “I Know,” by D. Savage. The mark on her cheek is blurry and soft, like a smudge of dirt. She is bobbing her head underneath a caption about how it feels when someone accidentally likes a social-media post that’s more than a year old. The lyrics offer the answer: “You say you hate me but you stalk my page, you fucking hypocrite,” Bonelli mouths.

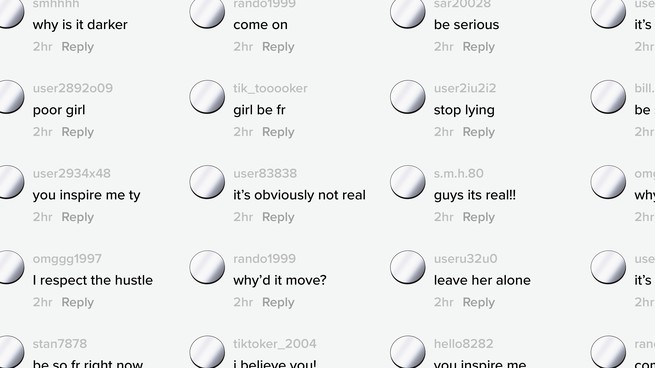

The comments section is filled with thousands of people pretty much admitting to doing just that. For nearly two years, hordes of sleuths have fixated on Bonelli’s face, united in a mission that has sent them scrolling through years of the teenager’s TikTok videos and back to this video in particular, where her mark is visible for the first time. They want to know the truth: Is the pretty, blond 18-year-old’s facial scar real, or did she fake it for online attention?

Read the full article.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. A new poem by Cortney Lamar Charleston.

“In grief and despair, / it is the soul that is heavy and the bones that are weightless.”

Watch. Magic Mike’s Last Dance, in theaters, is intimate and emotional without losing any of the franchise’s signature heat.

Play our daily crossword.

P.S.

The science journalist Betsy Ladyzhets returned to the subject of toilets and infectious disease last week, writing about the CDC’s recent move to potentially mine COVID-19 data from airplane-lavatory wastewater in airports across the country: “Airplane-wastewater testing is poised to revolutionize how we track the coronavirus’s continued mutations around the world, along with other common viruses such as flu and RSV—and public-health threats that scientists don’t even know about yet.” It’s worth a read.

I would also be remiss not to reiterate Jacob’s final plea in our discussion: Close your toilet lids before flushing. “If this conversation does even a little bit of good for the cause of closing lids, then it will have been worth it,” he said.

— Kelli

Isabel Fattal contributed to this newsletter.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest For Top Stories News Click Here