Pharmaceutical and biotech companies spent $85bn on acquisitions in the first five months of the year, marking a dramatic recovery in dealmaking as they seek to replenish their drug pipelines.

The surge in M&A, compared to just $35.6bn in deals in the same period of 2022 and $49.1bn the year before, according to Stifel, an investment bank, is being fuelled by large cash reserves amassed by Big Pharma during the coronavirus pandemic and investor concerns about future growth prospects.

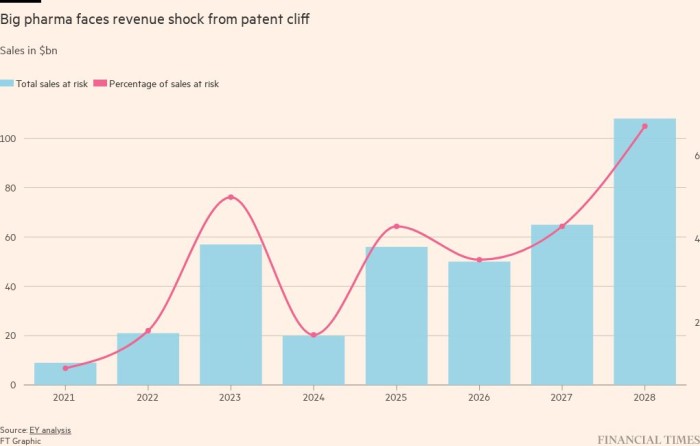

At the start of year, the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies held more than $1.4tn in dealmaking firepower, according to an analysis by EY. They also face the expiry of patents stretching to the end of the decade, which exposes $200bn of their top-selling branded drugs to generic competition and will squeeze revenues.

Pfizer, Merck and Sanofi have led the M&A revival this year by announcing multibillion-dollar acquisitions, even as dealmaking across other market sectors has fallen sharply due to rising interest rates and tighter bank lending.

“It’s a big turnround and completely bucking the overall trend in the M&A market,” said Tim Opler, managing director at Stifel’s global healthcare group. “If we maintain the pace of the first five months and a week we would be on track to have a $215bn year.” In 2022 the total value of biopharma deals was $127bn while in 2021 it was $149bn.

But at Bio International Convention, one of North America’s largest biotech conferences, last week in Boston, company executives, bankers and sector analysts were not celebrating the return of dealmaking. Rather, they were fretting about the rising threat that US antitrust regulators have begun a crackdown on consolidation in the sector.

Last month the Federal Trade Commission caused shockwaves when it sued to block Amgen’s takeover of Horizon Therapeutics — a $28bn deal announced in December that kick-started the nascent M&A recovery.

The FTC warned that “rampant” consolidation in the pharmaceutical sector was pushing up prices for patients in its first ruling in more than a decade seeking to block a merger in the sector. It deployed a novel argument, claiming the transaction would enable Amgen to use rebates on its existing blockbuster drugs to pressure insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers into favouring Horizon’s two monopoly products.

Amgen said it would fight the decision in court but this did not temper industry-wide concerns that the action would chill M&A activity when many smaller biotechs face funding constraints.

“Blocking that deal is absolutely uninformed. The more volatility there is the harder it is for investors to invest,” said Paul Hastings, chief executive of Nkarta, an early-stage biotech company specialising in cell therapies that target cancers.

Hastings, an industry veteran who is outgoing chair of Bio, the biotech industries’ main lobbying group, warned that US antitrust authorities’ tougher stance on pharma/biotech deals risks upending a decades-long business model that underpins innovation. This model attracts investors to biotechs that are pursuing high-risk research in the knowledge that large companies may later buy them and supply the funds needed to complete expensive clinical trials and commercialise new drugs, he said.

The importance of small to midsize biotechs to drug development has grown rapidly over the past two decades. Last year emerging biopharma companies were responsible for a record 65 per cent of the molecules in the R&D pipeline without a larger company involved, up from less than 50 per cent in 2016 and 34 per cent in 2001, according to the Iqvia Institute.

Bio’s concerns were echoed by Seagen, whose shareholders recently backed a proposed $43bn takeover by Pfizer — the largest deal in the sector since AbbVie agreed to buy Allergan in 2019.

Seagen chief executive David Epstein told the Financial Times that if the FTC took away the possibility of Big Pharma acquiring biotechs then “funding” and “innovation” would soon dry up in the sector.

“I hope that the FTC can come to understand how the ecosystem works,” he said in an interview.

The intervention of the FTC, which has taken a tougher approach to M&A under commissioner Lina Khan, comes at a difficult time for biotech companies that face capital constraints and the biggest shake- up in drug pricing in the US for decades.

Biopharma companies raised $54.6bn in funding last year, a drop of 54 per cent on 2021 and the lowest level of funds raised by the industry since 2016, according to a report published last week by EY. Rising interest rates, the seizing-up of IPO markets and the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank — one of the largest funders to the biotech sector — mean many companies are struggling to raise cash.

“Look at the financing challenges of the companies that have obviously less than two years of cash, and not all of those companies are going to survive,” said Rich Ramko, EY US biotech leader.

Last week Merck sued the US government over a new law that hands the federal government the power to negotiate prices for some of the most expensive drugs. The drugmaker alleged the drug pricing reforms — a critical part of President Joe Biden’s policy agenda — are unconstitutional and “tantamount to extortion”.

Experts say government regulators increased willingness to intervene in the sector raises uncertainty and risk for companies considering large takeovers.

“The odds that we wake up and see a J&J or Lilly do something big like buying Alnylam, Incyte or Vertex goes down from where it would have been,” said Stifel’s Opler.

But he said any chilling of M&A could be temporary as the FTC could be beaten in court given that many legal experts believe their case is not strong. “This could actually free up the market to do more deals without fear of antitrust agency blockage,” he said.

Kay Chandler, co-chair of the global life sciences industry practice at Cooley, a law firm, said dealmaking may take a bit longer and there could be a shift in how much risk companies are prepared to take on when considering M&A. But ultimately large pharma companies had no choice but to continue to pursue M&A because they had to fill the innovation gaps in their drug pipelines.

“I don’t think this changes the fact that companies do deals.”

After the FTC action against Amgen, analysts at investment bank Evercore forecast that a thawing in Big Pharma interest in megadeals would invariably shift “consolidation focus to smaller and earlier-stage biotech companies — and more of them”.

The next test for antitrust authorities involves Pfizer’s takeover of oncology-focused Seagen. The FTC must decide within days whether to extend the initial 30-day time period for a review of the deal, which is central to Pfizer’s efforts to return to growth after a sharp fall in Covid revenues this year.

“We could see a potential challenge to Pfizer/Seagen as this would represent an even larger transaction,” said Evan Seigerman, analyst at BMO Capital Markets, in a note published after the FTC sued Amgen.

But for the moment Pfizer and Seagen are confident their deal will not draw fire from the FTC, arguing there is no product overlap and that it would benefit competition and innovation.

“It’s not even unlikely, its like zero [chance]. It is not going to happen,” said Epstein, noting that the break-up fee Pfizer would pay Seagen in that event is almost $2.3bn.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Health & Fitness News Click Here