A near life-size photograph of the Nigerian ceramicist Ladi Kwali greets visitors at the entrance to Body Vessel Clay, a show on 70 years of black female potters at Two Temple Place in London. The photo is taken from a low angle, with Kwali standing behind one of her water pots and looking down towards the viewer. Her posture is confident and self-assured, but her gaze feels parental: a matriarch for the three generations of artists on display.

In Kwali’s home in the Gwari region of northern Nigeria, pottery traditions were passed down through matrilines, with communities of women working together to create wares fired at low temperatures. Their methods allowed for the production of large water pots that were light enough to carry, as well as other functional and ceremonial vessels. Kwali first learned to produce pottery from her aunt and developed such a talent that her work was collected by the emir of Abuja.

But Kwali took a decidedly audacious step. On “Water Pot” (1956-59), she signs her work with “LK” — not on the base but, prominently, near the neck of the vessel. It’s subtle, but disruptive. This is the action of a creator who understands the value of her work and is asserting her position as an artist. Similarly, although the work is labelled a water pot, it is not functional. Kwali hand-built the vessel in the traditional manner but employed glazing and firing techniques that rendered the pot too hefty to carry. She also meticulously etched lines into the soft body of the clay, creating alterations in colour and texture beyond the usual level of surface decoration for functional pots of this type.

This work, which is placed at the start of the exhibition, provides an embodiment of the hybrid techniques that Kwali and other artists employed at this time, and the theme of hybridity is carried through the exhibition, playing on the tensions between form and function, tradition and innovation, home and world.

One tension is embodied elsewhere in the show. In the early 1950s, British ceramicist Michael Cardew was charged with establishing the Pottery Training Centre in Abuja (now Suleja) by the Nigerian government while the country was still under British rule. The aim was for the centre’s artists to produce high-quality wares to appeal to domestic and international markets. From 1951, Kwali and other artists were able to train in British pottery techniques, such as wheel-throwing and using glazes, and combined these skills with their own traditions of hand-building vessels through coiling and pinching. The exhibition does well to contextualise this complex colonial history without making the error of centring Cardew or marginalising the voices of the artists in focus.

Kwali is a significant figure in this modern expansion of what ceramics could be. Her practice spans the periods before and after Nigeria gained independence in 1960, when the country was immersed in navigating issues surrounding post-coloniality. At this time, many Nigerian buyers preferred foreign ceramics to those with more traditional Nigerian aesthetics, and Kwali’s wares sold better overseas than they did in her home country.

The show highlights the work of Kwali’s lesser-known contemporary Halima Audu, who worked out of the Pottery Training Centre for two years before dying young. Like Kwali, Audu worked in a hybrid style — their works often look similar — and exhibited a mastery of symmetry and surface decoration. A quiet star of the exhibition is Audu’s “Lidded Bottle” (1959-65). To have painstakingly sculpted the stoneware jar with accompanying screwtop is remarkable: the two clay pieces twist together perfectly, a triumph of form and technique.

In 1974, Magdalene Odundo, who was born in Kenya and studied in England, started at the Pottery Training Centre, where she met Kwali, and a selection of pots she created on her return to England from Nigeria reflect a kinship between the two artists’ work. The selection of Odundo’s early pots at Two Temple Place have the wide-bellied shape of traditional water pots, with fine lines etched along the body. Rather than using glazes, she experimented with applying thin layers of slip (liquid clay) to create a sheen in painterly washes of grey and black. “Pot” (1984) exemplifies how Odundo’s style later shifted to smaller, smooth pots with sculptural forms that slink and bulge sexily.

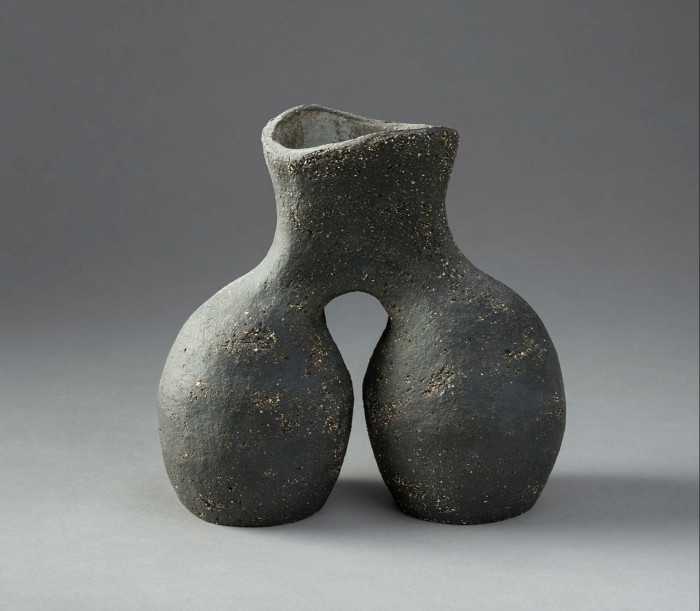

Bisila Noha, who is a generation removed from Odundo and two from Kwali, looks to a range of pottery traditions including the Native American ceramicist Maria Martinez, Japanese ceramics and the Ivorian artist Kouame Kakaha as inspiration. Noha’s piece “Kouame Vessel” (2021) does double duty in honouring Kakaha’s practice — both create two-legged vessels — while also exploring aspects of her own identity. She associates the two legs of the vessel with the idea of two entities converging to form something new. Noha is drawn to this concept, in part, because of her Spanish and Equatorial Guinean heritage, which the catalogue describes as sometimes giving her a “feeling of in-betweenness”.

A final room feels slightly abrupted from the rest, displaying works by artists who don’t necessarily have a direct connection to Kwali. Nevertheless, this section provides an important view into the practices of more contemporary black women artists working with ceramics and clay. This includes two films, “Clay” (2015) by Jade Montserrat and Webb-Ellis and “Burdened” (2018) by Julia Phillips, which engage with the materiality of the medium through performance, as well as pieces by Phoebe Collings-James, Shawanda Corbett and Chinasa Vivian Ezugha, which showcase the versatility of the medium.

Reflecting on the varied and conceptual works in this room, you understand how much work the “LK” signature truly does on Kwali’s “Water Pot”. Kwali was not only leaning boldly into her own artistry, but also creating space for other women to tap into ceramic and clay traditions as a potent form of creativity and expression.

‘Body Vessel Clay’ runs at Two Temple Place until April 24, twotempleplace.org

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here