It’s the exploration of human experiences — of how the desire for impermanent things morphs people into unhappy individuals and how humans can achieve liberation in the end by freeing themselves from greed.

This intrinsically Buddhist theme defines an art exhibition at Alliance Française de Dhaka. It’s an attempt to negate the modern notion that art and religion are two separate entities. But oriental art that forms the basis of the show is essentially sacred art, according to organisers. It all revolves around a sacred centre, a sacred origin and a sacred source.

Bringing together about 50 artists from Bangladesh and West Bengal, for the first time, the exhibition explores traditional expressions of Buddhist art within the region. It dares to suggest that humans can find common ground right in the heart of an angry, confused and divided world.

“It’s the celebration of truth, beauty and bliss, away from mundane desires that lead to suffering,” said Dr. Malay Bala, curator of the Dhaka-based Oriental Painting Study Group that organised the event.

Art and Buddhism

“This art is very much part of Buddhism and you can’t separate the two. If you go to Japan, and you go to one of the ancient temples in Osaka, there’s this massive golden statue of the Buddha,” Mikhail I. Islam, curator of the exhibition, said in an interview. “You cannot help but feel the sacred presence of the Buddha’s compassion or blessing or peace.”

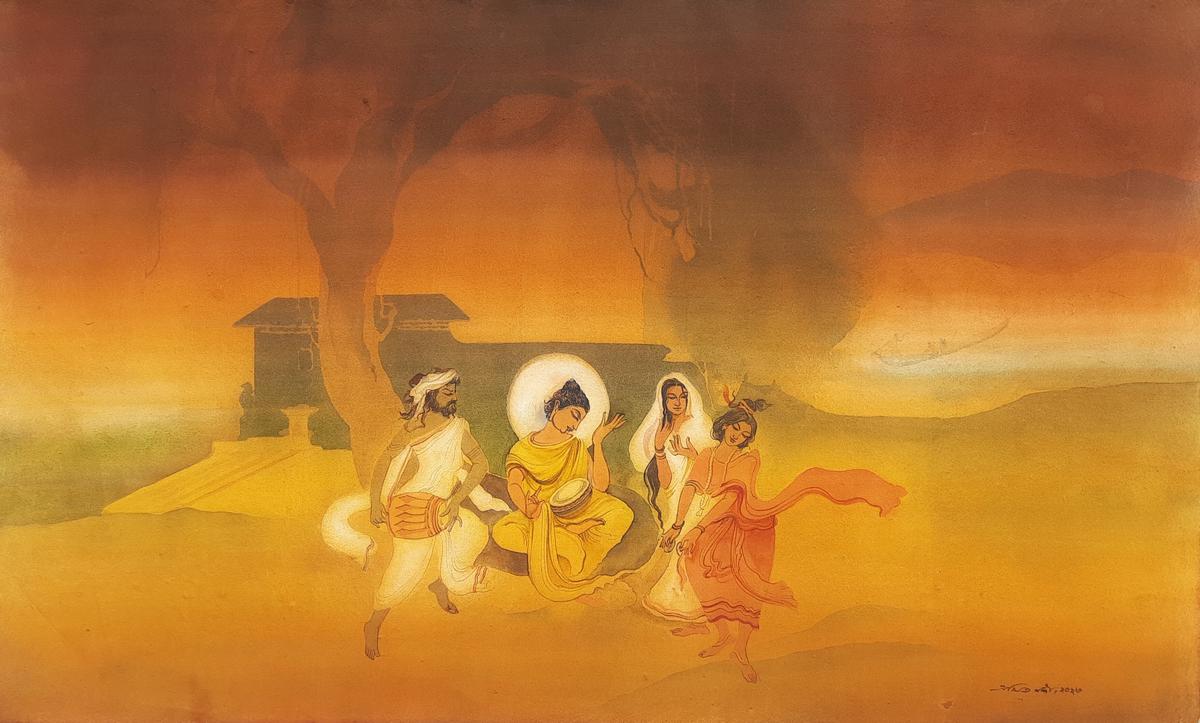

‘Baul Buddha’ by Amit Nandi

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Buddhist art is part of the Bengali identity in a region that blends all sacred traditions — Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism, and, to some extent, Christianity. “These are the traditions that form the bedrock of our culture,” Mr. Islam said.

The exhibition takes a new look at the story of Buddha and his life, capturing the entirety of the human condition. That means a closer look at any Buddhist narrative and paintings about his life reveals something that every human being in some way will be able to relate to. That’s the message the Buddha and the exhibition leave behind for the viewers.

None can save humans from sickness, old age and death; and no physician is immortal or infallible. All they can do is bring an undeluded eye to the human condition to see how they can ease some suffering. That seems to inspire the title of the exhibition — From Suffering to Liberation: Buddha of Bengal.

An exhibit of Buddhist art at the Alliance Française de Dhaka

| Photo Credit:

Arun Devnath

The exhibition was inaugurated on May 3 by the Buddhist Vante Sanghananda Mohathero, the high priest of Sylhet Bouddho Bihara. It will continue until May 15.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a project based on the Buddha’s life cycle divided into four stages: birth, renunciation, Buddhahood and Mahaparinirvana (the ultimate transcendent state). The project led by Amit Nandi, a teacher of oriental art at Dhaka University, is presented with 16 paintings with a sculpture of the Buddha in the middle. The experience of being in the presence of an image of the Buddha can be a quiet reminder of the human potential for compassion — the central plank of Buddhist belief.

Some of the Buddha paintings were presented in semi-transparent, pale layers of colour, accomplished through an oriental visual arts technique, known as “wash drawing”, said Mr. Bala. The technique mystifies the images of the Buddha, hallowing the backdrop and transporting the viewers back to the long-lost halcyon days.

“The fundamental difference between the Western and Oriental art forms, simply put, is that we see, absorb and internalise before we draw and the Western artists see and draw,” Mr. Bala said.

Paradox of sacred art

The artworks – all untitled and without the artists’ names – aim to connect human experiences, both unvaried and unique, with the life of the Buddha.

“You and I might be looking at a painting of Buddha, the same picture, but our whole life experience will totally contextualise what means to us. We might be looking at the Buddha when he is on the chariot and witnessing a sick man on the street. And each of us has experienced sickness in our family, but your experience of your nanny, and her sickness versus my younger cousins is going to be entirely different,” Mr. Islam said.

Yet, both can identify themselves with that human condition. In that way, there’s the paradox of sacred art: it contains something that is, in some way, absolute and something that’s relative.

Mr. Islam resists the concept of art curation, describing it as a modern Western concept, which has a worldview completely different from the Bengali tradition. “I think it was more about facilitating artists to see how they perceive the Buddha, how they experience and what resonates in his life,” he said.

“Whether we like it or not, Bengal is a religious community, a multi-religious community, in the best sense of the word. Our religious worldviews were so expansive and universal. In terms of Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam, if you go back to pre-colonial periods, you had Islamic philosophers sitting with Hindu philosophers discussing what the Vedas were saying. And Muslim scholars, comparing it to the Quran, were trying to understand what God was communicating through these two sacred texts,” Mr. Islam said.

This level of metaphysical exchange between two religions is unheard of in many parts of the world, but the legacy of collaboration has inspired people in Bengal for ages. And the key takeaway from the Buddhist art exhibition is the value of self-effacement and liberation from primary emotions and the ego.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here