Ports in the rest of Asia will need significant investment to match the capacity of Chinese harbours, according to analysis that shows how western businesses could struggle to loosen ties with the world’s largest exporter.

US and European companies have signalled their intent to shift some of their manufacturing from China to India and countries in south-east Asia, amid rising geopolitical tensions between Washington and Beijing.

However, shipping industry figures caution that other countries in the region will have to invest in ports infrastructure as well as manufacturing capacity to handle the mega-container ships that drive world trade.

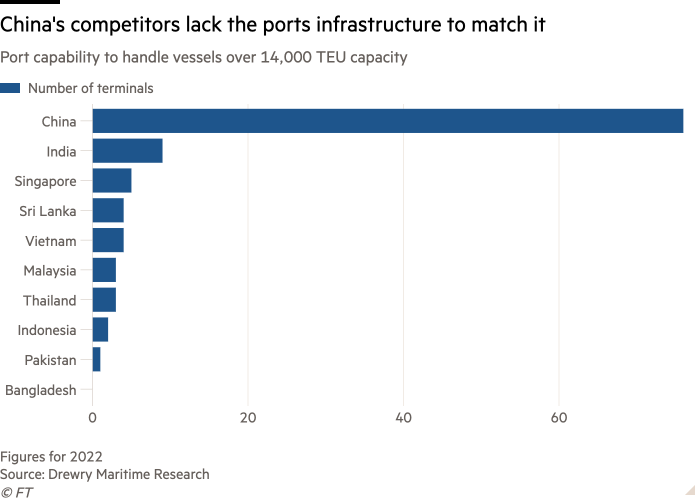

More than 80 per cent of goods are transported by ship, according to the UN. But data from research group Drewry shows that other Asian manufacturing hubs have a dearth of harbours able to accommodate the largest ships that have become essential for transporting goods from east to west.

While China has 76 port terminals able to support large ships carrying more than 14,000 20ft containers, south and south-east Asian countries have just 31 between them. Large vessels make up about two-thirds of the shipping capacity for services between east Asia and Europe, according to data provider MDS Transmodal.

Mike Garratt, chair of MDS Transmodal, said it was “a no brainer” that ports in other Asian emerging markets would struggle to process China’s container volumes without significant investment.

Glenn Koepke, general manager at supply chain monitoring group FourKites, said: “The power of China’s manufacturing and ability to produce and ship goods cannot be matched.”

The gap between Chinese ports and their rivals underlines how investment by Beijing has enabled China’s dominance as the world’s manufacturer-in-chief. The country invested at least $40bn between 2016 and 2021 in coastal port infrastructure, according to Shenzhen-based Qianzhan Industrial Research Institute.

The investment has meant the equivalent of 275mn 20ft containers could be handled at Chinese ports last year, up to 80 per cent more than the amount processed annually by all countries in south and south-east Asia combined, according to figures from data group Dynamar and the UN.

Garratt said “a great deal of investment” was required from other Asian emerging markets to catch up with China, adding that it generally takes port operators up to five years to build a new terminal.

Shipping groups have also acknowledged the industry faces challenges helping companies shift their supply chains away from China.

Dheeraj Bhatia, senior managing director for Hapag-Lloyd in the Middle East, said that while customers were expecting to import more from India, the country needed to do “a lot more” in terms of investment in ports capacity “to take advantage”.

“I don’t think this is going to be a quick shift,” Bhatia said. “It will take several years.”

In January, Hapag-Lloyd announced plans to acquire a 40 per cent stake in Indian operator JM Baxi Ports & Logistics.

Rodolphe Saadé, chief executive of CMA-CGM, told the Financial Times in early March that it could take “five or 10 years” for India and south-east Asia to build terminals for large ships and “play a different, bigger role”.

China itself has invested in infrastructure in Asian economies, such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan, through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Chen Yipeng, deputy general manager at COSCO Shipping Ports, said last week that the Chinese state-owned group was aware of companies planning to shift to south-east Asia and was “actively looking for opportunities”.

A significant increase in exports from elsewhere in Asia would also require shipping patterns to be redrawn.

China’s largest port, Shanghai, runs 51 weekly services to North America — more than twice as many as any south or south-east Asian hub, according to MDS Transmodal. Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh, south-east Asia’s best-connected port to North America, runs 19 services a week.

South-east Asian countries could help “mitigate risks” associated with China, but “we don’t anticipate major swings in the long term”, said FourKites’ Koepke.

Western-based multinationals are still planning to reduce their reliance on China, however.

According to a European Chamber of Commerce in China survey at the height of the government’s Covid lockdowns in 2022, almost a quarter of respondents were considering shifting current or planned investments in China to elsewhere.

Dale Buckner, chief executive of Global Guardian, said the security consultancy is helping a large company withdraw from China, with several people and production lines to be moved over the next three years. He said the business planned to shift manufacturing to Latin America as well as the Philippines.

Widespread sanctions on Russia have only deepened anxieties about a similar response if China were to invade Taiwan.

Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine had taught businesses a “key lesson”, Buckner said. “How do we protect ourselves as that relationship between China and the west is decoupling? [A] long-term worst-case scenario is you could lose your supply chain with China.”

Analysis by AlphaSense showed that corporate America is increasingly citing deteriorating Sino-US relations in the risk sections of their annual filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“Unsurprisingly, we reached a new high this year with general mentions of ‘geopolitical uncertainty’,” said Nick Mazing, AlphaSense’s director of research.

Additional reporting by Yuan Yang in London

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here