With I-70 through Glenwood Canyon once again closed indefinitely in both directions because of yet another accident — this time involving a tractor-trailer that was left dangling off the upper deck of the highway — you might wonder why an interstate was built through a canyon that’s perpetually at the mercy of Mother Nature. We answered that question in August 2021; keep reading for the whole story:

On the evening of July 29, a flood of muddy water, rocks, trees and other debris shot down the hillside above a section of Interstate 70 in Glenwood Canyon, rushing along a burn scar created by a wildfire in 2020.

The force of the mudslide blasted across the westbound section of I-70 and then exploded through the barrier wall, crashing onto the eastbound section of the highway below. The road became completely impassable.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration assessed the torrential rainfall that set the disaster in motion — the equivalent of 2.8 inches per hour in fifteen minutes — as “anywhere between a 100-year and a 500-year event,” says Keith Stefanik, the Colorado Department of Transportation’s deputy commander for the incident.

This portion of I-70 was completed less than thirty years ago, in 1992 — the last section of the interstate to be completed.

And Glenwood Canyon isn’t the only part of Colorado where the path of I-70 steered straight into trouble. In north Denver, the highway has been on a collision course with neighbors for decades, and now they’re ready to throw plenty of mud at officials who made the decision to keep it in their backyards.

And, in some cases, front yards.

When General Dwight D. Eisenhower took office as President of the United States in 1953, he brought many lessons learned during World War II to the White House with him.

As Allied Commander during the war, he’d been impressed with Germany’s autobahn system, which allowed high-speed movement of supplies and troops.

In the mid-’50s, as concerns of a potential military attack on this country by the Soviet Union grew, Eisenhower realized that the U.S. needed a system of highways that would allow people to flee major metropolitan areas if they came under attack, and also give the military an easy way to get weapons across the country. Building off decades of conversations in Congress, Eisenhower spearheaded the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 and the subsequent construction of the 41,000-mile National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, multi-lane interstate highways that would connect the country from coast to coast, from north to south, and many points in between.

Given Colorado’s location near the center of the country, it was inevitable that some of these highways would be in the state. Today, Interstate 25 runs right along the Front Range as it stretches from southern New Mexico on one end to northern Wyoming on the other. From its start in Denver, Interstate 76 heads northeast through Fort Morgan up into Nebraska before linking up with Interstate 80.

But factors besides location played a role in the routes of some interstates.

“Eisenhower’s wife was from Denver,” points out CDOT’s Bob Wilson. “Mamie Eisenhower had a house down there on Lafayette Street in Capitol Hill, and he would come here frequently to go fishing and see family. And the story goes that he used to go up to Grand County to go fishing a lot up in Granby. This was back in the day when presidents still rode in regular motor vehicles and weren’t helicoptered around to get away from traffic and potential danger, and he was coming back and got caught on Highway 40, which parallels I-70 west of Denver in that area around Genesee. And Ike was in a big traffic jam on Sunday afternoon coming back to Denver. It frustrated him so much that he made a point that this was a section of road that needed to be widened.”

“Ike was in a big traffic jam on Sunday afternoon coming back to Denver. “

tweet this

Wilson admits that this story has not necessarily been verified as totally factual, though “it does sound plausible because of his travels back and forth from Grand County,” he says.

As initially envisioned, I-70 — the major road leading through the middle of the country — was going to stretch from Baltimore, Maryland, to Denver. In 1957, the decision was made to take the highway all the way to Cove Fort, Utah, though the last connections would not be complete for decades.

Still, like other highways in the system, I-70 quickly proved to be a boon for the American economy, which relied on the system to smooth interstate commerce and ease the transport of both goods and people.

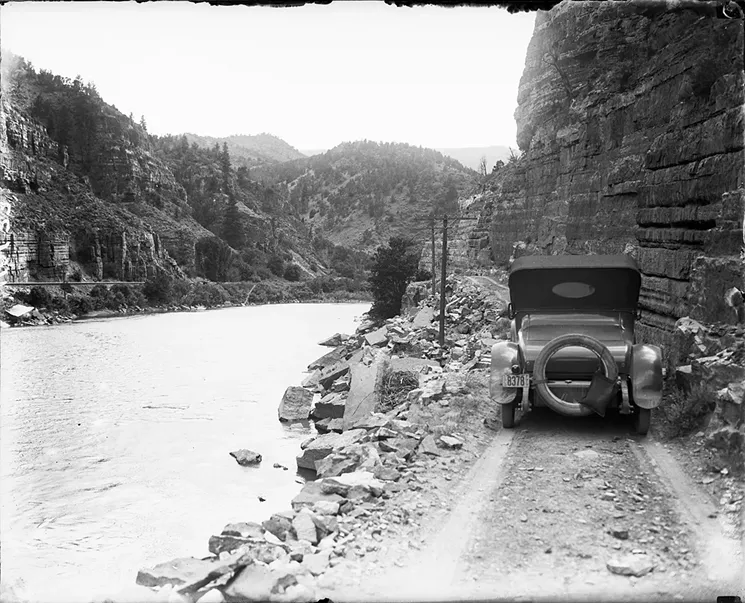

The interstate followed the path of an early road along the Colorado River in Glenwood Canyon.

Denver Public Library

Business dictated the location of many of Denver’s early transportation routes, including railroad lines. By 1880, dozens of railroad routes passed through Denver.

The railyards servicing those routes also attracted industry. Smelters were built along the lines in the communities of Globeville, Elyria and Swansea, small towns north of Denver that were later incorporated into the city. Globeville, which was established in 1889, became part of Denver in 1902, and the others soon followed.

“Globeville, of course, is named for the Globe Smelter, which was one of the largest smelters here,” explains Denver historian Tom Noel. “And so they moved down there along the Platte River, along the railroad tracks. There’s not much there but cheap worker housing. There was also the Swansea smelter, which gives its name to that neighborhood.”

Immigrants from Europe worked in the smelters. The Scandinavians were first, “then it switches to Poles, Slovaks, Eastern Europeans, Lithuanians, Latvians, Slavs, Slovenians,” Noel notes, adding that the smelter managers “liked to get a mix of groups so they couldn’t organize as easily, unionize as easily.”

In the 1940s, Denver officials and state highway planners started to mull the idea of establishing a major thoroughfare along 46th and 48th avenues. Back then, that strip of north Denver had the city’s worst traffic, and planners held a “belief that to be effective, highways must be placed where traffic was at its worst,” researcher Dianna Litvak wrote in her 2007 master’s thesis in history for the University of Colorado Denver, titled “Freeway Fighters in Denver, 1948-1975.”

By 1948, the route that would become I-25 was already cutting through the western portion of Globeville, and having a road head east from there made sense to planners, particularly since there was no strong political constituency in the area to argue otherwise.

In the late 1950s, federal highway planners added asphalt to injury when they suggested putting I-70 through this northern section of Denver, home to poor, working-class communities descended from immigrants. Local and state officials got to choose exactly where it would cut through the area.

“It was definitely built through a historically smelter community, so working-class people didn’t have the resources to complain or fight it,” says Lisa Schoch, a senior staff historian at CDOT.

“There was some protest from people, especially in Elyria-Swansea,” says William Philpott, a University of Denver history professor. “There was a citizens’ group there, and they tried to express concern that running this interstate through their neighborhood would turn it into a slum. They were especially concerned about this proposal to elevate the highway, elevate the freeway above street level. They felt that it would cut those neighborhoods north from the rest of the city.”

But despite opposition, plans went forward to have I-70 bisect the communities of Globeville, Elyria and Swansea, obliterating blocks of small houses and shops. “It seemed like there was no serious consideration of routing that freeway anywhere else except for 46th,” Philpott says.

Possible alternatives, such as establishing I-70 farther north along 52nd and 54th avenues west of I-25 were scrapped because of higher estimated costs and the fact that a northern route would require even more displacement of residents. “This was a time when highway planners had tremendous power to dictate where highways would go,” Philpott explains.

In fact, what happened in Denver was occurring in urban areas across the country. “I-70 in Globeville really is a continuation of many such examples of neighborhoods with the least voice ending up being cut in half by the interstate,” says Paul Chinowsky, professor and director of the Environmental Design Program at the University of Colorado Boulder’s College of Engineering and Applied Science. “You see in cities across the country that it’s primarily the underrepresented areas, the poorer socio-economic areas, that ended up having the interstate go right through their neighborhood.”

The I-70 viaduct that spanned from Colorado Boulevard to I-25 opened in 1964.

By then, many of the descendants of the immigrants who’d worked in the smelters had left the area, which was becoming more heavily Hispanic. The newcomers to Globeville and the neighborhood that is now known as Elyria-Swansea inherited the legacy of those manufacturing days: The area is one of the most heavily polluted in the U.S.

While much of that contamination was remediated after the feds declared the area around Globeville a Superfund site, the highway didn’t move. In fact, after years of debate over how to expand I-70 in Denver — and whether to move it out of the city altogether — CDOT doubled down and decided to expand it along the original footprint but put a significant section underground.

Residents and activists pushed for government officials to “ditch the ditch” and move this section of I-70 so that the neighborhoods of Globeville and Elyria-Swansea could be reunited without having to suffer further adverse health impacts from increased traffic, dust, noise and various other construction impacts. Some local officials joined the fight, but they didn’t get very far.

“Unfortunately, those decisions that were made back in the 1950s are really difficult to undo,” says Chinowsky. “And it’s extremely costly when you try and undo that.”

“Unfortunately, those decisions that were made back in the 1950s are really difficult to undo.”

tweet this

In 2017, CDOT signed off on final approval to reconstruct part of I-70 in Denver, in what’s known as the Central 70 project.

In the meantime, construction was already beginning all around I-70 closer to I-25, where a massive expansion of the National Western Complex had gotten under way. Although neighbors had been brought into the planning process, they complained then — and complain today — that they will see few benefits from the $1 billion project.

As part of the Central 70 project, CDOT opted to remove much of the viaduct and lower I-70 between Brighton and Colorado boulevards while expanding the highway as it runs through Denver. The Central 70 project broke ground in 2018, and CDOT expects traffic to start flowing permanently through the new sections by late 2022. A park will be installed over the underground portion of the highway after that.

But while the park will at least partially reconnect the old neighborhoods, many residents don’t consider it much of a consolation prize. “It’s really the same old,” says Denver City Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca, a native of Swansea who represents the affected areas. “They kept the park just shy of the square footage that would have required ventilation. It wasn’t really ever about the neighborhood.

“The park is not some place I would want to send my kids to play, given what the pollution is going to be like — just given the size of the highway and the already polluted air in that area,” she adds.

Farther west along I-70, the problem is less about what I-70 does to its surroundings than what its surroundings could do to the interstate.

As railroads were being built across Denver, in the late 1880s the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad established a route through Glenwood Canyon, which had been carved out of the mountains eons before by the Colorado River.

“Here, the Colorado River has worked its way down through 1.4 billion years of limestone, dolomite, quartzite, granite, gneiss, and shale, cutting a narrow, winding gorge where multicolored cliffs and promontories rise high above the roaring waters,” Philpott wrote in his 2013 book Vacationland: Tourism and Environment in the Colorado High Country.

In 1902, fifteen years after the first train ran through the canyon into Glenwood Springs, construction wrapped up on the Taylor State Road, which also wound through Glenwood Canyon. At the time, the “threat of floods, rock slides, and snow earned Glenwood Canyon the reputation as one of the most dangerous routes for travelers in Colorado,” noted a historic analysis prepared by architectural and engineering firm Mead & Hunt for CDOT in 2019.

Thanks to a push from state officials, improvements were made to the Taylor State Road along Glenwood Canyon in the mid-1910s.

In the 1930s, Congressman Edward Taylor of Colorado argued in Congress for further improvements. In 1936, Taylor State Road became part of U.S. 24, an early highway that crossed much of the country, and two years later, Works Progress Administration employees, hired through the New Deal, blasted away more canyon walls and widened the highway. When it reopened in 1938, it was a joint segment of U.S. 24 and U.S. 6.

But although the Eisenhower administration envisioned connecting the entire country with the interstate highway system, I-70 was originally designed to stop in Denver.

“There was a long history of the main transcontinental routes not going through Colorado.”

tweet this

“There was a long history of the main transcontinental routes not going through Colorado,” says Philpott. The first transcontinental railroad skipped Colorado, instead going through Cheyenne and crossing the Continental Divide at a lower altitude; Denver boosters paid to get a spur line into the city. And the Lincoln Highway, which is now I-80, also skipped Colorado for Wyoming.

If I-70 had stopped in Denver, Colorado wouldn’t have become a major thoroughfare for travelers, and its capital might not have become a popular tourist attraction.

But Colorado officials weren’t willing to let their state be bypassed this time around.

Following intense lobbying by these officials that included a promise that Colorado engineers could create an all-weather route by building what later became known as the Eisenhower Tunnel, the feds acquiesced. In 1957, the Bureau of Public Roads gave the green light for an additional 500-plus miles of I-70 between Denver and Utah.

But there was more rough road ahead. Highway planners were looking at building I-70 through Glenwood Canyon, following parts of the existing highway system. But that decision led to intense battles between engineers and environmentalists.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act into law, which required federal planners to conduct environmental reviews that included public and stakeholder input. By now, construction of I-70 was well under way and even finished in some stretches, but not the Glenwood Canyon area. Under NEPA, planners now needed to take human and natural elements into consideration.

In the early 1970s, highway planners weighed multiple options for the section of I-70 that had yet to be built in Eagle and Garfield counties. One was Glenwood Canyon. Another was building the highway through the Flat Tops Wilderness Area north of Glenwood Canyon, which would hit an elevation of over 10,000 feet and cross through a sensitive wilderness area, according to the Mead & Hunt analysis. Third on the list was following Cottonwood Pass southeast of Glenwood Springs, which would have required a 6 percent grade for over eight miles and also would have added 9.4 miles to the route.

Glenwood Canyon won out as the best option. “It was the most direct route, and highway planners love directness,” says Philpott.

But many were unhappy with this choice. One group fighting highway planners was Citizens for a Glenwood Canyon Scenic Corridor, which counted singer-songwriter John Denver as its honorary director. “John Denver’s group, for one, fought well into the 1980s for the canyon road to remain just two lanes,” writes Philpott. “For their efforts, they were mercilessly marginalized.”

In 1975, highway planners were able to strike a compromise with those pushing for preservation of the canyon: The engineers would get to build a larger highway to replace the two-lane U.S. 6, while also observing environmentalist demands that construction not totally alter the canyon environment.

In 1981, CDOT began construction on the twelve-mile stretch of I-70 through Glenwood Canyon, which has rock walls that can reach well over 1,000 feet above the Colorado River at its base. In the decade that followed, engineers took great care not to harm the canyon landscape or habitat. Their work was lauded nationally.

“An excellent example of how the reformed process works is the Glenwood Canyon project on Interstate 70 west of Denver, one of the only major highway routes west from Denver over the Rockies,” wrote Jonathan Gifford, a transportation expert, in a 1993 issue of the Wilson Quarterly. “The canyon it passes through is a popular recreational spot which has long drawn large crowds of hikers and picnickers during the summer months. Legions of day-trippers once parked along both sides of the old two-lane road, which regularly choked up with heavy truck and recreational traffic, becoming both an annoyance and a hazard.”

Close to a decade of construction costing $490 million resulted in what then-Federal Highway Administrator Thomas Larson described in 1992 as “a world-class piece of environmentally sensitive engineering” and “a scenic byway that is one of the wonders of the interstate system.” Larson helped christen the new four-lane section of the highway with Governor Roy Romer at a ribbon-cutting ceremony in October of that year.

But building the highway was just part of the job. The real work came in dealing with Mother Nature.

There have been fires by Glenwood Canyon before, floods in the canyon. But the mudslides of this summer were unprecedented. And then there are the ramifications of climate change.

After a major push that included federal emergency funding, on August 14 CDOT was able to partially reopen the interstate — one lane in either direction through the hardest-hit portion in Glenwood Canyon — after a two-week closure. But threats of rain again closed the stretch temporarily a day later, and much repair work remains to be done.

Chinowsky believes that the state and federal government need to revisit the design of this stretch. “You can invest the money to at least try to mitigate the risk that is involved,” he says. “It’s going to take a lot of money, it’s going to take a lot of engineering and construction time. But if we don’t invest it at this point, the long-term economic impact is going to be huge.”

CDOT plans to look at the stability of the nearby rocks, increase capacity for handling mudslides, and also work with the U.S. Forest Service on creating water retainers on the land above the canyon. “We’re focused on resiliency through this area. I don’t see a possibility of rerouting I-70,” Stefanik says. “I-70 is going to stay I-70 through Glenwood Canyon.”

CDOT has also begun discussions with county officials about bolstering nearby routes so that when I-70 is closed by a mudslide in the future, other roads can better handle the detoured traffic. Cottonwood Pass, in particular, has already come up in conversations between CDOT and Eagle and Garfield counties, according to Stefanik.

“We’ve come to think of that route as natural,” says Philpott. “They can’t picture it without that link. But the route of I-70 was not natural at all. It wasn’t inevitable at all. But once it’s there, it comes to seem natural, it comes to seem inevitable.”

“The problem with Glenwood Canyon is that it was a great concept, a great design, but it was also completely unrealistic to think that you could control the elements that were around it,” concludes Chinowsky. “You are in a canyon. When you are in a canyon, canyons have water, mud, boulders. Everything that has been happening, I’m absolutely sure there were engineers at the time who gave the warning: ‘This is going to happen. You are in a canyon. You are in Colorado.’”

Correction: This story has been updated with the correct street of the house where Mamie Eisenhower’s parents lived.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest For Top Stories News Click Here