Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Jan. 17. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Newsletter

Get our free Coronavirus Today newsletter

Sign up for the latest news, best stories and what they mean for you, plus answers to your questions.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It’s been more than three years since the start of the pandemic, and there are still plenty of things that have researchers scratching their heads. At the top of that list is long COVID.

The condition is so poorly understood that there’s no agreed-upon definition of what it is. Nor does it have a universally accepted name. “Long COVID” is the one we see most often, but others include long-haul COVID, chronic COVID and the medical establishment moniker PASC (which can stand for post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection).

Long COVID is characterized by a range of health problems that can last months. In some cases, symptoms have lingered for a year or more. The more severe a patient’s initial bout with COVID-19, the greater the risk of developing long COVID. However, it can also be triggered by an asymptomatic coronavirus infection, which means people can get long COVID without realizing they’ve had COVID-19.

The U.S. government’s working definition of long COVID states that symptoms are present at least four weeks after “the initial phase of infection.” Those symptoms can be a continuation of the original illness or can appear after a patient seemed to make a full recovery. The number and type of symptoms can vary greatly from person to person, which makes the condition complicated to understand.

Luckily for us, a group of researchers in Israel conducted a study of hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 patients and the myriad symptoms documented in their medical records. As my colleague Corinne Purtill reports, the research team focused on people with mild cases of COVID-19, as opposed to those who were sick enough to be admitted to a hospital.

Each of the nearly 300,000 people who tested positive for a coronavirus infection was matched to another person of the same age, sex and vaccination status. Both members of a pair also shared a similar suite of preexisting conditions, such as diabetes or immune deficiency disorders. The main difference was that the matched “controls” hadn’t tested positive for a coronavirus infection.

The researchers compared the medical records of each infected person and their uninfected counterpart for a period of 12 months. That allowed the team to gauge the risk of developing various long COVID symptoms and see how long they tended to last. The results were published last week in the medical journal BMJ.

Long COVID patient Barry Bwalya, who struggles with breathing and memory issues, is assisted by his wife, Barbara, at a hospital in London.

(Kirsty Wigglesworth / Associated Press)

The bad news is that even people with mild COVID-19 face an increased risk of developing long COVID symptoms. The better news is that the list of symptoms is comparatively small, and most were gone within a year.

For instance, among the 76% of study subjects who weren’t vaccinated against COVID-19 when the researchers began tracking them (primarily because the vaccines were not yet available), those who tested positive for a coronavirus infection initially faced a higher risk of developing a persistent cough than did their peers who tested negative. But within four months, the risk for people in both groups was the same.

Hair loss — a common physical manifestation of acute stress — was more likely to afflict those who tested positive than those who tested negative, but the elevated risk didn’t last beyond seven months. The pattern was the same with heart palpitations and chest pain, though it took eight months for the risks to equalize in both groups.

There were a handful of symptoms that were more likely to bedevil the infected after an entire year. Chief among them were the long COVID classics anosmia (loss of smell) and dysgeusia (loss of taste), which were reported by former COVID-19 patients at twice the rate as their uninfected peers. However, that was an improvement from the six-month mark, when former patients were 5½ times more likely to be struggling with loss of smell or taste.

Other symptoms that were more likely to affect COVID-19 survivors a year after their infections were shortness of breath, weakness and problems with memory and concentration.

The researchers said men and women were equally likely to see long COVID symptoms resolve within a year.

If you’re a glass-half-full kind of person, these results should be reassuring. Long COVID symptoms can greatly impact quality of life, and the months move by slowly when you’re debilitated, but at least you know that in the vast majority of cases, those symptoms will be gone by the first anniversary of infection.

Even so, advocates for long COVID patients remind us that there are no guarantees when it comes to recovery.

“There is a substantial number of patients who have a very long-lasting chronic illness, who are now going on three years of unrelenting illness,” said Lauren Stiles, a member of the Long COVID Alliance‘s executive committee.

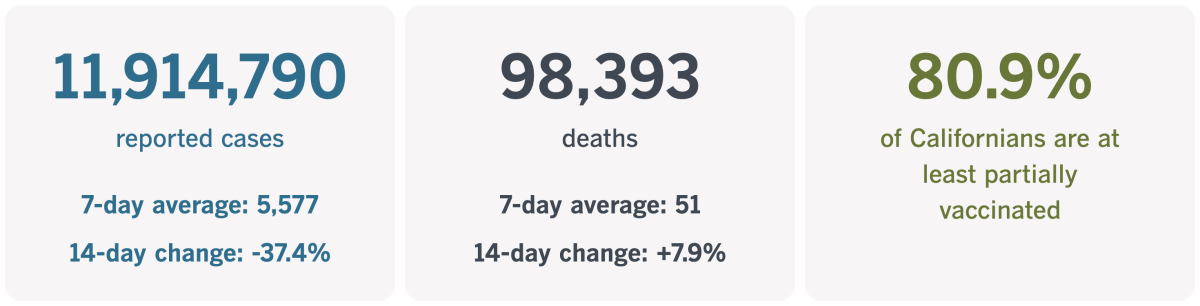

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:30 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

The value of talking to strangers

If you’re still working from home, relying on Amazon and Instacart to deliver items you used to shop for in person and streaming movies on Netflix instead of seeing them in the theater, then you’re depriving yourself of an important type of social interaction.

Yes, it’s vital to keep up with close friends and family members — the people with whom we have “strong ties,” in sociology-speak. Dozens of studies have documented the benefits of having a strong social network. Researchers say it’s as good for your health as quitting smoking.

It turns out there’s also a benefit to having “relational diversity.” That means having multiple kinds of interactions with people.

Here’s an example of a day with relational diversity: You start off sharing breakfast with your spouse. On the way to work, you stop for coffee and have a chat with the barista. Your time in the office includes conversations with co-workers, and you call a friend to catch up while you slog through your evening commute. After you get home, you say a brief hello to the neighbors as you take your dog for a walk, then head out to the monthly meeting of your poker group.

A COVID-conservative person who’s still semi-isolated might have just as many interactions over the course of the day, but it’s likely they’d be concentrated among a small group of family members, co-workers and close friends.

Hanne Collins is a graduate student studying organizational behavior at Harvard University. Her research has found that the more social interactions a person has overall, the higher his or her well-being. What’s more, Collins found that the diversity of those social interactions is also a predictor of a person’s well-being. In fact, social diversity was a stronger predictor of well-being than whether a person is married!

Taking a minute to chat with a barista is a simple way to improve your well-being.

(Eduardo Contreras / San Diego Union-Tribune)

Those findings suggest it would behoove us all to strike up conversations with people we don’t know very well, like the barista and the neighbors.

“We’re not saying that weak ties are equally important as strong ties, but our close [friends and family] are around us; we’ve built them into our lives,” Collins told my colleague Deborah Netburn. “There is value to fostering relational diversity and making those other connections happen.”

A generation ago, before we could use smartphones to order takeout meals delivered by a robot and arrange to have our prescriptions, dry cleaning and other essentials dropped off at our doors, we had no choice but to interact with strangers on a regular basis. Now it’s the kind of thing that makes some people uncomfortable, said Nicholas Epley, a professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago‘s Booth School of Business.

Epley’s research has shown that people tend to underestimate the delight they may derive from a conversation with a stranger. For instance, he asked people who rode the bus or train to work to predict how much they’d enjoy talking to a fellow commuter versus keeping to themselves. Most respondents expected to be happier alone, but they were wrong — talking to a stranger actually improved their commutes.

If this has you thinking about ways you can spend more time talking to people you don’t know very well (or at all), Collins has a few suggestions. When she moved to a new town, she enrolled in a guitar class to meet other adults. If a music class isn’t your thing, you could join a hiking group or book club.

During the pandemic, Collins started volunteering for a crisis hotline. She also makes a point of calling friends to check in instead of relying on text conversations.

“It’s little things like that that help us get over our fear of talking to people,” she said.

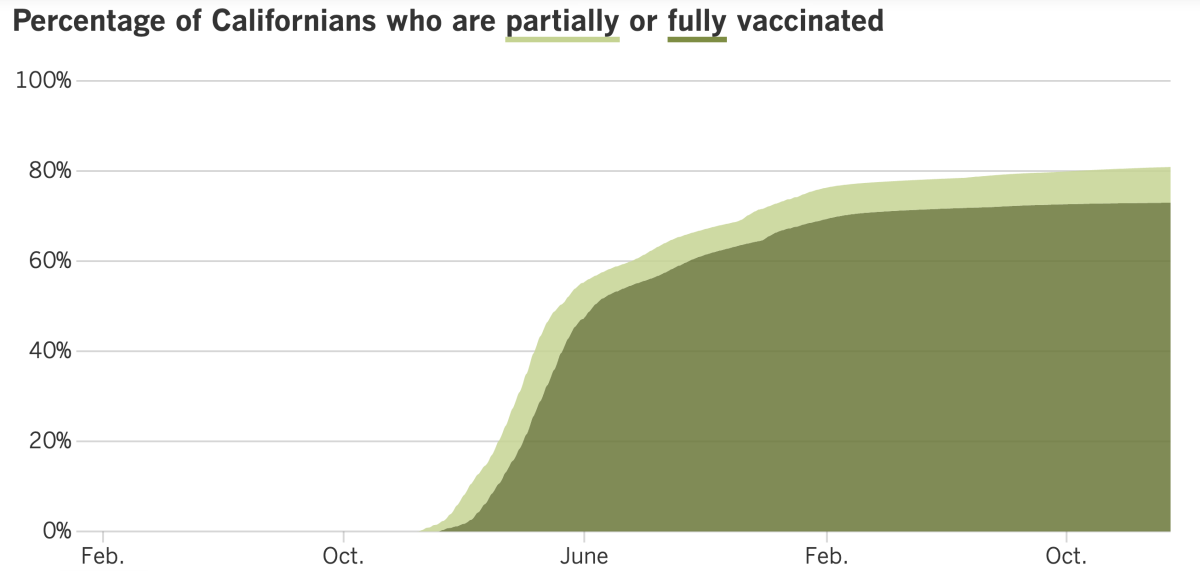

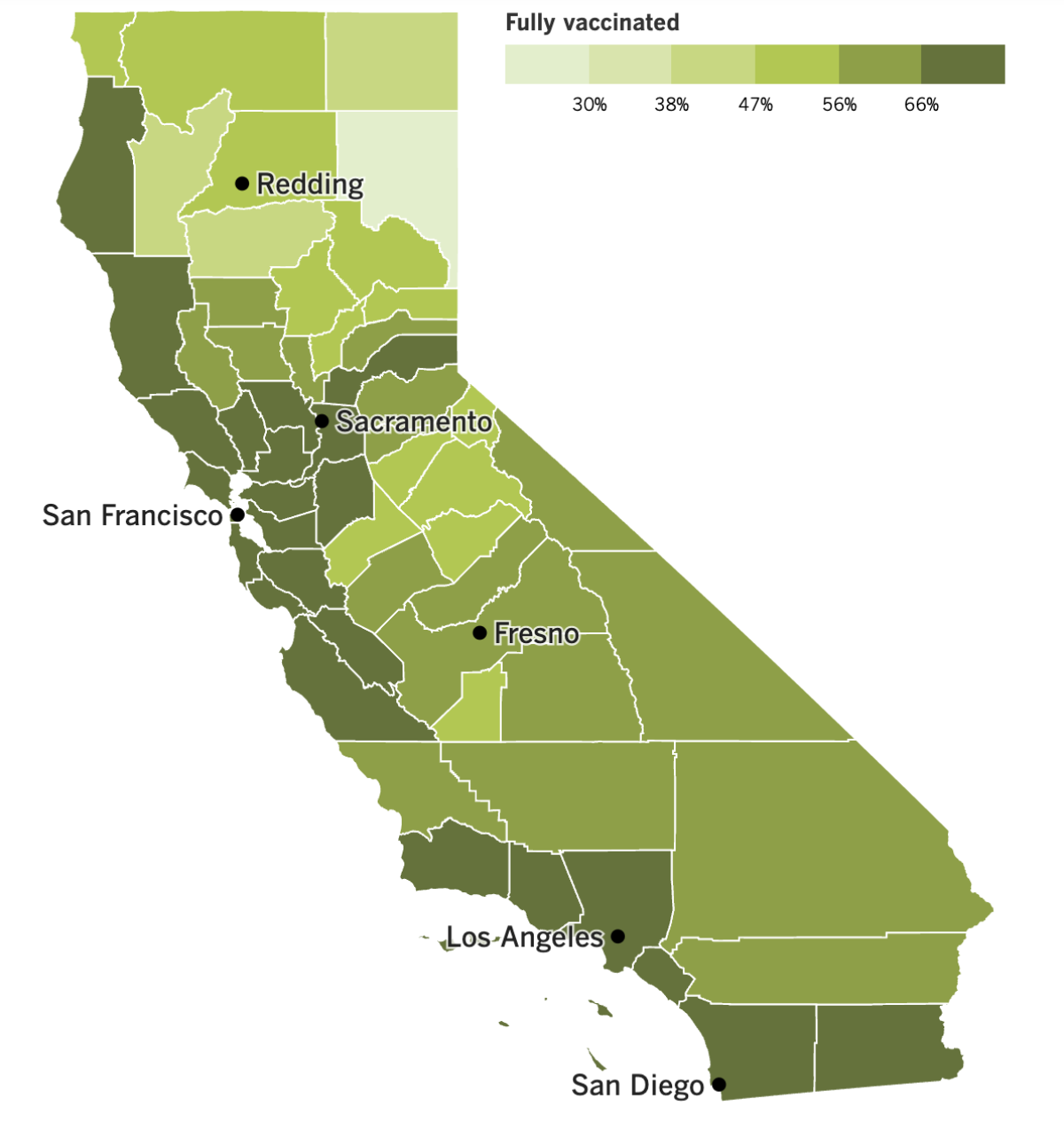

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

In other news …

Let’s begin with some of the worst news we’ve seen in nearly a year: In Los Angeles County, 164 people died of COVID-19 in the reporting week that ended Wednesday.

We throw a lot of numbers at you in this newsletter, so you might have lost track of whether that number is high or low. It’s high — the highest weekly death toll the county has seen in 10 months. For the sake of comparison, L.A. County’s worst week during the summer surge had 122 deaths.

It looks like 164 may turn out to be the high point for the winter. As of Tuesday, the county’s rolling weekly death tally has declined slightly, to 159. But it’s still up there.

“Deaths are high, and it’s really upsetting,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

It’s not clear why deaths have risen so much when the number of confirmed infections is comparatively low. In the summer, the weekly case rate peaked at 476 infections per 100,000 county residents; during the current wave, it peaked at 272 per 100,000 (in the first week of December).

COVID-19 has been especially deadly for older people. In the last three months of 2022, the mortality rate for county residents ages 80 and up was nearly 5 times higher than for people 65 to 79. Likewise, the mortality rate for those younger seniors was five times higher than for residents 50 to 64.

Senior citizens have been more vulnerable to the coronavirus all along, but Ferrer speculated that it’s even more true now because many have gone too long without a dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Although 93% of county residents 65 and older are fully vaccinated, just 38% of those eligible for the Omicron-targeting booster have received it. Ferrer called that figure “sobering” and said more boosters would prevent hospitalizations and deaths.

She also raised the possibility that some of the people catching the coronavirus now are also sick with other viruses — like RSV or influenza — that make it harder for them to recover.

The “tripledemic” of viruses is a concern to some Latino parents whose children attend schools in L.A. Unified. They’ve asked the district to reinstate a mask mandate through the end of January (at least) and to resume weekly coronavirus testing.

“We’re concerned about a return to school without any clear preventative health protocols in place by L.A. Unified to protect our children from acquiring a respiratory virus infection,” they wrote in a letter to the district.

The parents are members of a group called Our Voice: Communities for Quality Education. Most of them are from low-income or multifamily households in East and South Los Angeles. If a kid becomes infected at school, it could affect not just the child’s health but the financial stability of the extended family.

LAUSD Supt. Alberto Carvalho has recommended that students, teachers and other district staffers wear masks to curb the spread of respiratory viruses. He also urged parents to get their children vaccinated against COVID-19. Dr. Smita Malhotra, the school district’s medical director, offered the same advice.

“Thanks to science, thanks to vaccinations, thanks to therapeutics,” Malhotra said last week, “we are now in a place where COVID-19 … is similar to … RSV and flu. And so, as we have entered this new season of high respiratory illnesses, we’re treating this like we have treated all of the respiratory viruses.”

The members of Our Voices don’t speak for all parents, and there are plenty who don’t want to see a return of the district’s strict coronavirus controls.

“The mask mandates and the testing were a complete waste of our tax dollars,” said one Westside parent. “So much learning, mental/physical/emotional health was lost.”

But the Our Voices parents aren’t getting worked up over nothing. Countywide, the number of case clusters tied to schools and youth programs rose from 27 in early October to 64 the week before Thanksgiving to 226 just before winter break. Ferrer said that pattern is concerning.

Speaking of schools and vaccinations, a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that immunization rates among the nation’s kindergartners fell again during the 2021-22 school year.

In normal times, at least 94% of kindergarten students are vaccinated against measles, tetanus and other diseases. That mark was missed during the 2020-21 school year as the pandemic disrupted all kinds of routine healthcare. The fact that the vaccination rate dropped to about 93% the following school year is probably a sign that vocal opposition to COVID-19 shots has undermined some parents’ confidence in vaccines in general, CDC officials said.

Back to the situation at home: There are some positive signs that the post-holiday surge public health officials feared may not materialize. Official coronavirus infections in L.A. County — and across the state — have fallen in recent weeks. And although that might be due in part to unreliable case counts, wastewater surveillance also suggests that virus levels are dropping.

COVID-19 “did seem relatively flat over the holidays,” said State Epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan, and officials are hopeful that “we’re out of the woods.”

L.A. County reported 1,857 cases over the week that ended Thursday, down 19% from the prior week. That works out to 129 cases per week per 100,000 residents. (Anything above 100 is considered high.)

The CDC says the county’s COVID-19 community level is “medium,” a designation shared with Orange, San Diego and Ventura counties. Riverside, San Bernardino and Santa Barbara counties have low COVID-19 community levels. Only one California county — Mariposa — is currently classified as “high.”

Things don’t look nearly as good in China. Officials there said the country experienced 59,938 COVID-related deaths since early December. The National Health Commission said 5,503 of those deaths were due to respiratory failure caused by COVID-19, and the rest involved hospital patients who had COVID-19 along with other ailments.

The wording of the announcement suggested that there may have been additional COVID-19 patients who died in their homes.

Government officials said the “emergency peak” of the surge may have passed. The number of people seeking treatment at fever clinics plunged from 2.9 million on Dec. 23 to 477,000 last week, they said.

Health experts outside of China greeted the figures with skepticism. And The World Health Organization renewed its call for Chinese officials to share more information about their outbreak.

Dr. Albert Ko, an infectious disease physician at the Yale School of Public Health, said China’s official toll is artificially low because the country counts COVID-19 deaths in a very narrow way. Patients meet that definition only if they suffer respiratory failure and die in a hospital — and hospitals are concentrated in large cities, he said.

Ko said he’s nervous about people traveling to rural areas to celebrate the Lunar New Year.

“We’re really worried about what’s going to happen in China as this outbreak moves to the countryside,” he said.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: When I wear an N95 mask, is it mostly protecting me from other people’s germs, or does it protect them from mine as well?

The answer is that an N95 will do both, especially if it is worn correctly, with a tight seal around the face.

“It will have benefits for you, and it will have benefits for them,” said Dr. Aaron E. Glatt, chief of infectious diseases at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y.

The same would be true for any mask, though the lower the quality, the less protection it will provide — in both directions.

You shouldn’t assume that your mask is equally effective at blocking other people’s germs as it is at blocking yours. For instance, if you wear a regular surgical mask, it will do a good job of trapping your infectious droplets before they reach other people. But it won’t offer you the same level of protection against other people’s Omicron particles, said Dr. Luis Ostrosky, chief of infectious diseases at UTHealth Houston and Memorial Hermann Hospital.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

(Chinatopix / Associated Press)

The photo above was taken in Shanghai. That sunny space is a funeral home, and the people with masks are waiting for the cremated remains of their loved ones.

The crowds at crematoriums are just one indication that the death toll in China is far worse than the government has let on.

Zuo-Feng Zhang, who chairs the epidemiology department at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health, told Bloomberg that 59,938 sounds like a reasonably accurate count of deaths in hospitals, but it “might be the tip of the iceberg” when it comes to the total number of COVID-19 deaths across the country.

A report from Peking University estimated that 64% of the Chinese population had become infected with the coronavirus by mid-January. Assuming that 1 out of every 1,000 infected people died of COVID-19 — a conservative case fatality rate — that would imply that about 900,000 people had died since early December, Zhang said.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Music News Click Here