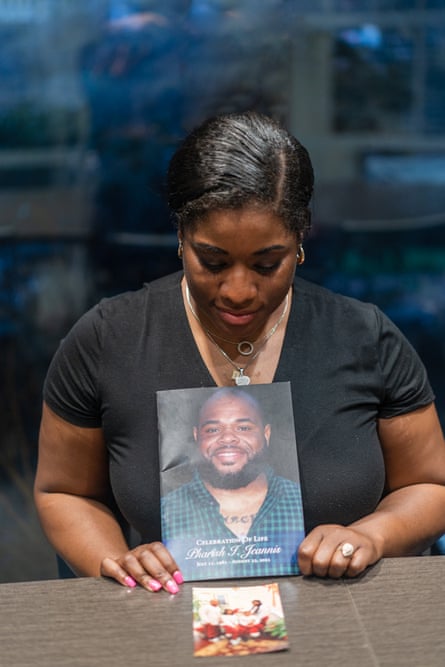

Pharish Jeannis was “a man among men”, in the words of his wife, Elashia Hall-Jeannis. He served in the army and survived being shot in Kuwait, receiving a Purple Heart medal. He never got sick. He always made their children, Journee and Anthony, laugh.

Then, in the summer of 2021, he got a cough that wouldn’t quit. After about a month of borrowing the nebulizer his wife used for her asthma, one Wednesday night in late July, when they were out on a date, Elashia suggested, “Maybe you have Covid.”

They were both fully vaccinated. Pharish worked at a pharmaceutical company in Covington, Georgia, and was keenly aware of the virus and its dangers.

On 30 July, he tested positive for Covid. On Monday, 2 August, the first day of school for their elementary school-aged children, Elashia was driving to her job as a social worker at an Atlanta homeless shelter when she got a call from her husband.

“Come home now. I can’t see!” he said. Pharish was diabetic. At the local hospital’s emergency room, doctors thought he might be in diabetic shock.

Within days, the 40-year-old’s lungs appeared “white” in X-rays, Elashia recalls, showing that he was losing the ability to breathe. After several weeks in the hospital, Pharish got on the phone one day and told Anthony, who was then six, “If I don’t make it home, remember to always do what I told you to do.” What he meant has remained a secret that Anthony has yet to reveal to his mother.

Pharish Jeannis died on 22 August.

That day, Anthony and Journee, Pharish’s 11-year-old daughter from a previous marriage, entered deep grief – and Elashia soon embarked on an isolating, often frustrating quest to find her children help in coping with their family’s loss.

Her children joined an estimated 245,000 children across the US who have lost one or both parents to Covid and an estimated 10.5 million Covid orphans worldwide, according to the Global Reference Group on Children Affected by Covid-19, an international consortium studying the issue, and the London-based medical journal BMJ.

Many have complex needs that cut across bureaucratic silos – from grief counseling, mental health support and school transitions to formalizing a grandparent’s guardianship or securing public benefits.

But despite the profound implications for these children, their families and their communities, Covid orphans have been largely overlooked in policy responses to the pandemic, according to people working on the issue.

‘Everybody’s tired of talking about Covid’

In February, an advisory board in California began working on designing the most ambitious response in the US to date, a $100m fund that will be disbursed to Covid orphans (as well as children who have been in foster care) meeting certain requirements when they turn 18 – including being from low-income families.

But the California program, called Hope, for Hope, Opportunity, Perseverance, and Empowerment, has not been replicated elsewhere in the US, and although President Joe Biden underscored the urgency of caring for children orphaned by Covid in May of last year, the federal government has yet to address the issue directly with national policies or programs.

“Everybody’s tired of talking about Covid,” said Emily Walton, policy director at Covid Survivors for Change, an organization that helps people experiencing long-term impacts of the virus and works to prevent future pandemics.

As a result, “in general, the public is not aware of the problem” of Covid orphans, said Catherine Jaynes, who works on children, Covid and bereavement with the Covid Collaborative, a coalition of experts on education, the economy and health.

Jaynes’s group helped put together Hidden Pain, a 2021 report on the pandemic’s toll. The report notes that children of color have been disproportionately affected by loss during the pandemic. This mirrors the disproportionate impacts seen in the general population.

Black children in the US, like Journee and Anthony, are twice as likely as white children to have suffered loss of a parent or caregiver, according to the international consortium, which includes Imperial College London, Harvard University, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. Although about 39% of children in the US are Black or Latino, 61% of Covid orphans belong to these categories, said Susan Hillis, co-chair of a group in the consortium.

Half of the nearly quarter-million US children who have lost one or both parents live in only five states – California, Texas, Florida, New York and Georgia, according to Hidden Pain. Georgia’s place on that list, ahead of other, more populous states, reflects higher rates of conditions such as diabetes, obesity and heart disease, which contribute to higher rates of death from Covid, said Hillis. About one-third of Georgians are Black, and the state is now home to an estimated 5,552 Black children who have lost a parent or caregiver due to Covid – the second-highest nationwide, after Florida. But Georgia, like most states, has not developed a comprehensive statewide policy to address the issue.

Finding Covid orphans

Research on epidemics such as HIV/Aids shows that, without adequate help, children across the country grieving the loss of important adults in their lives are at risk of immediate and long-term affects ranging from falling behind in school to drug and alcohol abuse and even physical illnesses such as heart disease, Hillis said.

The suddenness with which many parents or caregivers died of Covid was particularly difficult for children, she said. Covid orphans may experience depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety, which can in turn affect learning in school.

Other countries offer models for locating children facing this loss, Hillis said. An example: several years before the pandemic, Brazil added a field to all death certificates indicating whether the deceased has left behind anyone under 18 at home. Social services agencies can then monitor the wellbeing of those children. Such a system is now helping to locate children affected by Covid.

Hillis said she has spoken with colleagues in Malawi and Zambia, where public agencies and faith groups have experience responding to children orphaned by HIV/Aids, about replicating Brazil’s system. Other possibilities include relying on schools for referrals, or using digital medical records to locate next of kin, she said. But no country is far along in addressing the issue, she added.

Dr David J Schonfeld, a pediatrician and director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, said schools in the US can play a role in identifying children who have lost a parent or caregiver during the pandemic – although there is no national plan for doing so, and Schonfeld said he hadn’t seen evidence of schools adopting such plans.

“You can find out who’s grieving. If you’re a teacher, all you have to do is ask. Those who have caring relationships with children can find out,” he said.

At the same time, Dr Schonfeld said, teachers “should know how to support a grieving student. You can acknowledge loss and show you care. You don’t have to counsel them.”

A system that didn’t know how to respond

When Elashia’s husband died only weeks into the school year, she found herself facing a school system that didn’t know how to respond to her family’s loss. Shortly after her husband tested positive for Covid, she quarantined her children for 14 days, to avoid spreading the virus at their school. Then, when her husband died, the children missed more days of school to be with extended family in South Carolina.

“I began having trouble with truancy officers,” she said. “I told them their father had died.”

Then, she struggled to find a therapist or other professional who could help her children cope with their grief.

“Everything was virtual. I couldn’t find anyone to communicate with,” Elashia said. “‘We can only do online sessions,’ they told me. With a six-year-old, how are you gonna talk to him about death on the phone?”

Once they returned to classes at Newton County Theme school, a public school in Covington, both children began having difficulty. Anthony didn’t participate in class. He would cry. Journee, in sixth grade, “had breakdowns every day”, Elashia said.

The school counselor told Elashia, “I’m not a grief counselor,” while the school district’s psychiatrist told her: “I don’t do therapy; I just do diagnosis,” Elashia recalled.

“I found myself fighting with the school clinician,” Elashia said. “They were unprepared. They told me to call their pediatrician. They thought my son had a learning disability, and wanted to make an IEP [Individualized Education Program, for receiving special education services]. I said, ‘He just lost his father!’ He was grieving.”

A Newton County schools spokesperson, Sherri Partee, did not respond to specific questions related to Anthony and Journee’s experience, but said in an emailed statement that school system staff “stand ready and willing to assist our school district families in times of need”. In addition to social workers and school counselors, the school district has a crisis response team and a partnership with a local behavioral health center, she said.

Eventually, Elashia wound up putting Anthony in Rocky Plains elementary school, another Newton county public school, where he found a counselor he can talk to “when he’s having a bad day”. She home-schooled Journee for more than a year, only enrolling her again in a public middle school in January of this year.

Now, both are “thriving”, she said, beaming.

‘A complete life-changer’

It wasn’t until late 2021 that Elashia found an effective source of help for her grieving children. A colleague at work told her about Kate’s Club, an Atlanta non-profit that has been working with children and grief for two decades.

This, she said, was a “complete life changer”. At Kate’s Club, her children found “other kids who went through the same thing. They’ve built good relationships here.” Her son Anthony, who for months after his father’s death “didn’t want to talk about it”, was now “talking to other kids. Some of them even went to his school.”

The organization was founded on the idea that “there’s power in a child being with other children who are grieving”, said Lisa Aman, executive director.

“Covid highlighted the need for this work,” she added. About 70% of the hundreds of children who come to her organization for activities ranging from exploring grief through art to playground games are Black or Latino, Aman said.

Since the onset of Covid, children are showing up at Kate’s Club with more signs of distress. Suicide ideation is up 60%, Aman said. She has increased programming due to Covid, including a launching a new project to train Georgia juvenile justice system workers on working with grief in children.

Children dealing with grief

The Hidden Pain report includes suggestions for using all levels of government, possibly backed by federal funds, and partnering with the private sector, to identify children who have lost parents or caregivers. It also centers schools, community organizations and faith-based organizations as places where children could be getting help dealing with their grief, and names the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services, as the federal agencies that could help “expand grief-competence” in these local settings, through increased training.

Julie Kaplow, in her work as executive director of the Trauma and Grief (Tag) Centers at the Hackett Center for Mental Health in Houston and the Children’s Hospital New Orleans, is training school counselors on how to work with children who have lost someone to Covid, including 500 counselors at the Dallas Independent school district this year. A child dealing with grief exhibits behaviors that “look like conduct problems”, she said. “It looks like a ‘bad kid.’”

She’s trying to get counselors and teachers to “shift from, ‘What is wrong with the student?’ to ‘What happened to the student?’ … [and] from blaming a child to understanding a child.” Her centers are also working with churches and other religious organizations interested in learning to help children deal with Covid-related losses.

“I’ve been very surprised at the lack of funding directed towards responding to grief,” Kaplow said, regarding efforts to get state legislatures and Congress to fund such training. “People are so ready for the pandemic to be over that they don’t want to acknowledge deaths are occurring – and that the deaths that have already occurred will affect children for years to come.”

At the federal level, Dr Schonberg observed, “the issue is if you’re trying to reply to a crisis, there’s not a great funding system in place.”

‘A permanent sentence of poverty’

Households dealing with the loss of a parent or caregiver “are disproportionately low-income and susceptible to sudden income loss, and many need imminent economic support”, according to the Covid Collaborative’s report. Mexico, Peru, Colombia and South Africa are each developing programs to give Covid orphans grants or monthly stipends, according to the BMJ.

In California, state senator Nancy Skinner developed Hope after she “saw the pandemic was disproportionately affecting low-income families, particularly families of color – almost like a permanent sentence of poverty.” Nearly 38,000 children in California have lost a parent or caregiver to Covid, according to the Global Reference Group for Children Affected by Covid-19; almost two-thirds were Latino.

The group that began working on implementing the Hope program is determining how to find children who have lost parents or caregivers and cross-reference for income, as well as other parameters for disbursing funds to these children when they turn 18.

Moving forward, children living with loss due to the pandemic – and their families – will need a broad range of assistance, from funds for 18-year-olds, such as in California’s program, to peer support or counseling and even practical information such as how to obtain social security survivor benefits, said Emily Walton, of Covid Survivors for Change.

“There’s consequences for all of us when children are suffering – when they grow up and don’t reach their full potential,” said Walton. “Children are innocent – they didn’t ask for this.”

Meanwhile, Elashia has been making sure her children hold on to the best memories of their father. This past Christmas, her daughter, now 13, dressed up as Santa Claus, just like Pharish used to do. Journee left out a glass of milk, and took a bite out of a cookie. Even though Anthony knew it was her sister, the family took joy from repeating the ritual, and sharing stories of Pharish’s antics. Her husband, she said, “was a goofball. He gave us a great life.”

-

Youth Today is a national, non-profit newsroom covering issues affecting children and young people. Subscribe to Youth Today.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Covid-19 News Click Here