Think of it as a building with a delightful buzz. The National Insect Museum in Bengaluru is home to the world’s largest moth, longest insect and tiniest wasp. Also preserved in caskets, liquids and freezers are ants, butterflies, beetles and worms.

The museum, hidden within the lush campus of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research-National Bureau of Agricultural Insect Resources (ICAR-NBAIR), will make you see moths. Consider these numbers: The two-storey structure, inaugurated in 2019, contains over 2 lakh mounted specimens and slides, from 11 insect orders, stored in temperature- and humidity-controlled spaces. It has another 4 lakh wet (preserved in alcohol) and cryo-preserved specimens; and a heritage collection with specimens over 100 years old.

“What distinguishes this collection from others is that every insect has some sort of agricultural relevance,” says M Nagesh, director of the ICAR-NBAIR in Bengaluru. “They are either beneficial or pestiferous, or have the potential to be either.”

Over 10 years in the making, NIM is meant primarily as a resource for researchers but does mark certain “open days” by inviting the public in. (There isn’t a calendar of these, so it’s best to call ahead to find out when the next one is.)

More than half the insects at NIM have been procured over the last 15 years by ICAR taxonomists, says Ankita Gupta, the entomologist in charge of the museum. Collecting insects is a two-pronged process; some can be collected only by day, others only at night. Day collections involve setting out bright yellow collection bowls filled with water and an adhesive. Night collections involve setting up light traps.

Taxonomists usually head into a region and set out traps to see what they’ll attract. But sometimes, they go looking for a particular species, like the elusive giant stick insect in the tea gardens of Valparai, Tamil Nadu. “We must have gone at least three times over 10 years, looking for it in the torrential rains, but it’s so hard to spot,” says Gupta.

A specimen of the order Phasmatodea was finally donated by P Mahendran, an entomologist from the United Planters’ Association of Southern India, a tea research foundation in Coimbatore, who found it on the institute’s campus.

In neighbouring Yercaud, also in Tamil Nadu, ICAR taxonomists finally found a specimen of the world’s tiniest winged insect, the Kikiki huna, which is two-tenths of a millimetre in size. “It’s a parasitic wasp which you cannot see with your naked eye,” says Gupta, who specialises in parasitic wasps. “But it has all the systems an insect should have — six legs, wings, a reproductory and a respiratory system.”

It was recorded in India for the first time in 2013, in the Eastern Ghats. “We might have had it before, but were unable to see or salvage it,” says Gupta. “It’s so tiny and it floats on the surface of water. At the time of sieving, which we do multiple times with very fine mesh, it might just have slipped through.” It remains a prized find.

This, along with the rest of the collection at NIM, has been digitised and is publicly accessible on the institute’s online database. (Actually viewing the species would require a microscope and special permission.)

WINGED THINGS

NIM is broadly divided into three rooms. One holds the samples collected most recently, mounted in wooden caskets that are stacked in movable metal shelves in a temperature controlled room. A much bigger room holds just the beetles (the order Coleoptera is the largest among the insects’). “In due course we will get thousands more,” says Gupta. “We pretty much get them in gunny sacks.”

The third room holds the museum’s heritage collection. Unlike the new, modern facility, insect specimens here are kept in wooden cabinets that date back 50 to 100 years. A strong smell of industrial camphor hangs in the air. “Most of these specimens were collected before ICAR was formed, when it was the British-run Commonwealth Institute of Biological Control Indian Station,” Gupta says.

The beauty of an insect collection, she adds, lies in how long it persists and how many researchers get to study it. NIM’s heritage collection is therefore invaluable. “There are specimens from entire lifecycles, gathered in remote regions of the Himalayas, in a time when researchers would camp out to rear and preserve insects and document every pest associated with a host plant,” Gupta says.

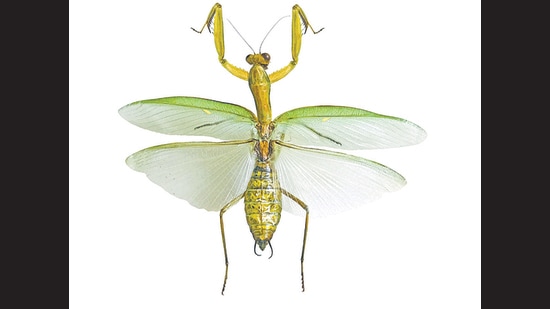

As it turns out, the institute’s greatest treasure is not quite an insect, she adds, though those are immensely precious; not the beautifully preserved butterflies, leaf insects, or even the praying mantises that mimic orchids.

She locates a small wooden box, not much bigger than her hand, and holds it out. In it lie three larvae specimens, one yellow, one black and one green. They’re the result of a lost art where the larvae of insects were mummified by sucking out the internal sap, disinfecting each husk, and inflating it with just enough air to not burst the outer skin. “This preservation was secured in 1960 and they managed to maintain the exact shape of the larvae,” Gupta says.

Such samples are rare in the world. This is the masterpiece in our collection, Gupta says.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here