As in many Arab cities, a conversation with a taxi driver in Cairo – or sometimes simply a ride in one – takes the pulse of the place. On my first night in the city, I jump in a shaky white cab that is passing my hotel and we enter the tentacular traffic of the Nile Corniche. After examining me in his rear-view mirror for a bit, the taxi driver engages me in a conversation that very quickly drifts from pleasantries (where I am from, what I am doing in Cairo) to his life, his job, then the traffic, then the people. “I don’t know why everyone is always running here. The country is not in its best state, but oddly enough tourists are back and things are working without us knowing how.”

This easy familiarity, so improvised and unexpected, turns the encounter into a theatre scene. In a few moments, the driver has condensed the current condition of Egypt into a few words – its perennial hardships and rises and falls since the 2011 revolution that toppled autocrat Hosni Mubarak. He has also summarised the way people feel and behave here, with more or less similarities: their emotional exhilarations, their cautious hope and, of course, the lightness, the comic relief, the forever joie de vivre, which they express with the term maalesh (“It’s fine”).

That same night, I cross the Qasr El Nil Bridge towards Tahrir Square, near which you will find at Shaheen Caviar the most perfect local batarikh (bottarga), thinly cut on toasted bread (preferably Egyptian aish baladi), with olive oil, sliced garlic and a sprinkle of lemon zest. On my way, I observe a young cotton-candy vendor blowing pink clouds into the wind; motorboats ripple the Nile waters with their neon lights. And just like that, from one instant to another, a city that seems so turbulent, so tense and intense, offers up something akin to sweetness. It’s the switch from one state to another that follows me all over Egypt.

It’s an intoxicating blend that has stirred the hearts of many travellers. Rarely before 2022 have its monuments and museum institutions attracted so much interest – and so much tourism, local and foreign alike. According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS), international tourism bounced back in the first six months of 2022, with almost 4.9 million tourists recorded – an increase of 84.5 per cent compared with 2021. Among the draws are the recent opening of the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation, with its impressive hall of mummies, 22 in total, transported to the museum amid a grand parade in April 2021; 4 November will mark the centennial of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter in Luxor. Around the same time, the long-awaited Grand Egyptian Museum is slated to open – a site of almost 500,000sq m, 3km away from the Pyramids, housing a gallery of 100,000 artefacts as well as a colossal statue of pharaoh Ramses II. Most recently, Dior announced that Kim Jones would present his men’s pre-fall collection in front of the Pyramids of Giza on 3 December.

Of course, the renewed appetite for Egyptology has played a significant role in the overall enthusiasm towards Egypt. But despite the majesty of its history, Cairo is oddly a city that doesn’t give the impression of being stuck in the past. On the contrary, it’s morphing and evolving, both on the urban and cultural fronts.

If you include the two recent satellite cities known as New Cairo and 6th of October, Cairo spreads over some 3,085sq km. A car ride here feels like a journey through numerous settlements condensed into one – all different in shape, like sediments from different layers of time: Fatimid, Mamluk, Khedival, then the modernist architecture, all connected by their sandy hues and the gleaming desert light. On both sides of the Ring Road, a massive highway that binds the city, the buildings are cut open, revealing pastel interior walls. Maha El Kadi, an Egyptologist who works with local specialists Abercrombie & Kent, tells me: “In early 2021, we woke up from one day to another with a different landscape here: the government had decided to demolish around 400 buildings to enlarge this road, among others. People were evicted and provided with alternative housing.” A year later, amid a so-called road-building campaign, the government also razed large parts of the City of the Dead, Cairo’s oldest cemetery, which doubled as a working-class neighbourhood. Several of the iconic Nile Houseboats were removed, and a few, among them the one on which the Nobel Laureate Naguib Mahfouz wrote, were destroyed.

To counter this arbitrary erasure of treasures from the past, several private initiatives were launched; one that had already been created was Al Ismaelia. Its co-founder, Karim Shafei, describes it as the first company dedicated to finding life for things that otherwise would be earmarked for destruction. “Our focus is in Downtown Cairo, where we acquire and rehabilitate historic buildings [ranging from 80 to 120 years old]. Our vision is very different from the developments in suburbia, where the experience is totally manufactured.”

One of Al Ismaelia’s projects has been the refurbishment of the mythical Cinema Radio, built in 1932, where Umm Kulthum performed several times. Cairo’s Downtown is in general a survey of the abundance of architectural movements that have shaped the Egyptian capital, from art deco to art nouveau, brutalism and postmodernism. In his book Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, Mohamed Elshahed – who also runs the enlightening @cairobserver Instagram account – has mapped out over 120 years of architectural developments. The book is an invitation to remember the city through its urban fabric, but also a call to arms to protect its inestimable heritage; those buildings that each echo back to a moment in time, or at least remind us of its passage.

I stop for a coffee and chocolate-coated dates at an outpost of the cult Groppi café where, among the pastel meringues, mounted like sculptures on silver platters and satin tablecloths, poets, writers, journalists and politicians used to gather and rethink the world. Its derelict but somehow chic interiors still hold the memory of an opulent past. Next to it is the Stephenson Pharmacy, founded in the late 19th century by the British chemist George Stephenson and sold to the Samman family in the early ’40s. The artist Yasmine ElMeleegy produced a long study on the different objects found in the pharmacy, from apothecary jars and glass syringes to prescription records; today these are presented in a sort of cabinet de curiosités. The Stephenson Pharmacy was recommended by my New York-based friend Nadia Gohar, co-founder of tableware brand Gohar World with her sister and HTSI columnist Laila; the Gohars source most of their table linens in Egypt. “There is an overwhelming amount of craftsmanship and expertise in Egypt,” says Nadia. “Materials and methods that people have refined and passed down for generations. We want that to last.”

One man who was similarly set out to preserve such artisanship was architect Ramses Wissa Wassef. At the oasis-like centre he created in 1951 – a paragon of his architectural language with domed mud-brick structures and a garden overrun by bougainvillaea and date-tree leaves – Wassef made it his mission to protect the imperilled artistry of weaving. His strategy was to introduce children from the nearby village of Al-Harranya to tapestry making. “But kids with no pre-defined ideas,” clarifies Ikram Nosshi, the centre’s current director. “[There are] two rules: no criticism and no copying. Why? To allow the kids to be as free as possible and avoid critical correction. Those who are familiar with western art always end up imitating it.” Of the 15 first-generation weavers, two are still here, alongside younger ones – all slowly constructing their tapestries in the vaulted workshops next to the museum.

Nurturing and protecting their indigenous crafts is a common concern among the younger generation of Egyptian artists. In a country of so many totemic, ancient icons, these creatives are eager to train our focus on keeping skills alive. Certainly it’s what spurred the illustrator and product designer Ahmed Hefnawy to launch Cairopolitan, his gallery and concept store, in 2006. Inside, objects borrow the shapes of prosaic elements of Cairo daily life: taxi signs, traditional aish loaves, local cigarette packs. “We’re driven by the belief that it’s not only our pharaonic history that embodies the spirit of Egypt but also the practical details of contemporary life in Cairo – a city which, after all, has been a home to [various] subcultures for a long time.”

After a lunch at Koshary Abou Tarek – a cornerstone of Cairene cuisine, where people queue for the inimitable koshary made of chickpeas, pasta and lentils – I meet Karim El Hayawan, an interiors architect and photographer who in 2014 launched Cairo Saturday Walks. “It’s an organic movement that evolved from my spending my Saturdays by myself, exploring and shooting in Cairo’s streets,” he explains. “Friends joined and it went viral. Now we are 500 members, local and international, and we have an annual exhibition [of photography] with the proceeds donated to one of the visited areas.” El Hayawan’s atelier is located in the district of Zamalek, which is also home to the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art. “Egypt has one of the oldest Schools of Fine Arts [outside of Europe], and some of the most important modern masters of the Middle East are Egyptian, such as Mahmoud Saïd and Mahmoud Mokhtar,” says Mai Eldib, head of Middle East sales for Sotheby’s. “One of the auctions I work most closely on is our biannual sale of modern and contemporary art from the Middle East, and Egyptian art is one of the biggest sectors.” Here in Zamalek, an ecosystem of galleries has flourished: among the players are Ubuntu, Tintera, Art Talks and, a bit further out in Maadi, the Gypsum Gallery.

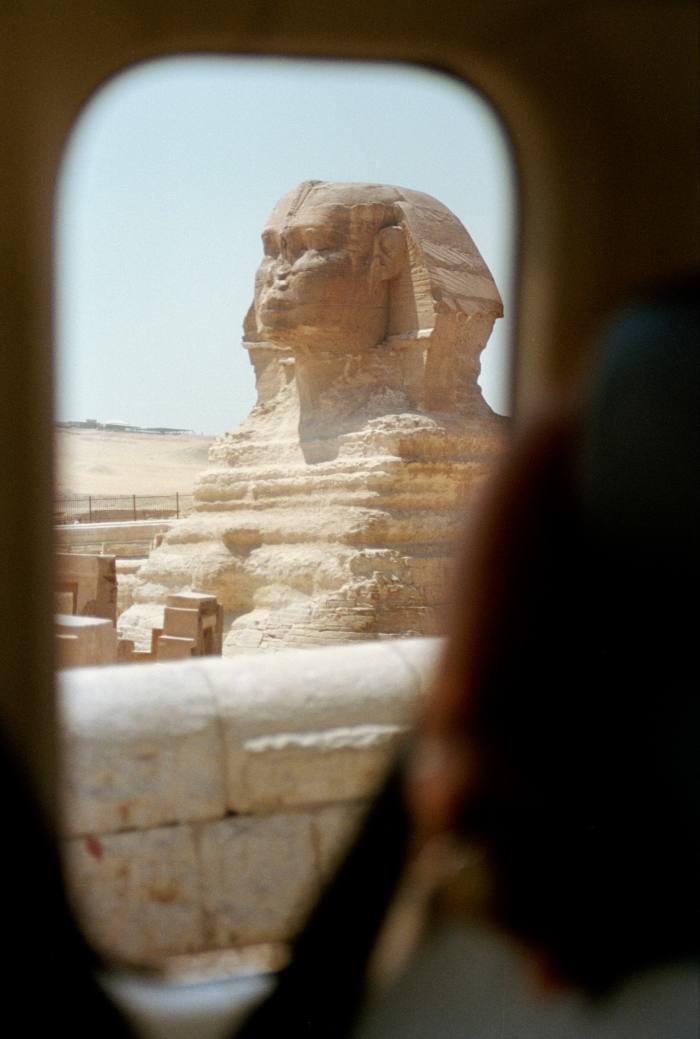

Nabila Abdel Nabi is Tate Modern’s first international curator to specialise exclusively in the Middle East. “The current cultural landscape in Egypt is incredibly diverse,” she says. “Organisations range from those [smaller] galleries to the monumental.” By monumental, she of course refers to the historic landmarks and institutions of the likes of the Egyptian Museum, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun – built in the ninth century, with its minaret believed to have been inspired by the lighthouse of Alexandria, it’s Cairo’s oldest – and the Pyramids of Giza. In each of these, the depth of Egyptian civilisation simply hits you, and reduces shifts in cultures to mere instants. What explains the infinite power of the Pyramids, however, is not the just the grandiosity of those eternal limestone mountains but the mystery of their making: 4,500 years into their existence, archaeologists are still trying to understand how their builders managed to move more than two million limestone and granite blocks, each weighing between 2.5 and 15 tonnes, from the banks of the Nile to Giza, passing through a desert en route.

On my last night in Cairo, I dine with the cultural conservationists Mounir and Laila Neamatalla at their family apartment overlooking the Nile. Epitomising a vanishing Cairene elegance, the siblings have for decades extended their Egyptian roots, and projects, to the Siwa Oasis in the Western Desert, which has been inhabited since 10,000BC. Mounir decided to create a sustainable development in the region in 1996, long before this notion became fashionable and commonplace. His Adrère Amellal is one of north Africa’s first ecolodges; meanwhile, Laila founded a programme through which older Siwa women train the younger generation in the craft of embroidery. “It was my way to empower them, and make them feel that they can be independent financially from the men in their families, which is not uncommon in this community,” she says. During the pandemic, she also launched the lifestyle brand Udjat, in collaboration with French designer Louis Barthélemy. “Siwa is a place where you’re out of time,” says Laila, wearing one of the gorgeous golden necklaces she’s been making since 1982 under the name Nakhla, for which she draws inspiration from Pharaonic aesthetics.

I sail south on the Nile from Luxor to Aswan. It’s a journey that, like Siwa, makes one feel slightly out of time. Luxor, the legendary Winter Palace – intact, rundown, but as lavish as ever – still echoes with British-colonial influences: the silverware, the untouched furniture, the maîtres d’hôtel and the abundant gardens. The Luxor Temple, reopened in November 2021, enchants totally when the setting sun travels through its restored Avenue of Sphinxes. At the Temple of Khnum at Esna, I see the internal pillars, restored and fascinating after being covered for some 2,000 years. Next, the Temple of Horus in Edfu, one of the best preserved and the second biggest after Karnak. Finally, reaching Aswan in the south, I come to the temple complex of Philae. It was built under Nectanebo (380-362BC), before being moved in the ’60s from its original location amid fears that it would become submerged by the waters; it now appears magnificent, as though floating on the Nile.

These milestones in the history of the Egyptian civilisation seem connected one to the other by the landscape: rows of date trees folding over carpets of papyrus, bamboo-like grass and ochre dunes of sand. Sometimes a farmer and his cow; old boats slowly swaying in the waters; mud-brick houses crushed under the sun. Images which have remained unchanged since antiquity are wrapped in that iridescent light that makes the Nile shine differently at each hour of the day.

My trip ends at the Old Cataract hotel, a chic yet understated palace from 1899 with terracotta walls and windows framed in white that overlook Elephantine Island and, further away, a Nubian-era village. Although it is commonly known as the place where Agatha Christie wrote Death on the Nile and François Mitterrand fell for the country, the Old Cataract is, still, an underestimated treasure. Atop a granite hill, it’s enveloped in the same silence that followed me throughout the cruise, surrounded by the same almost-surreal views. From my room, beyond the date palms, I see felucca boats bending in the wind. Here again, I feel out of time. But out of time and not back in time because Aswan, as everywhere else along the route of the cruise, is not only a door to delve, first hand, into ancient Egypt. It is an invitation to zoom out and collect the layers of different worlds that have accumulated on this land. And this is what most likely accounts for Egypt’s endless magic: that it has somehow outlived time.

Gilles Khoury travelled as a guest of Abercrombie & Kent (abercrombieandkent.com) which offers an eight-night trip to Egypt from £4,500pp including flights, transfers, two nights in Cairo, a Nile river cruise and two nights in Aswan

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Travel News Click Here