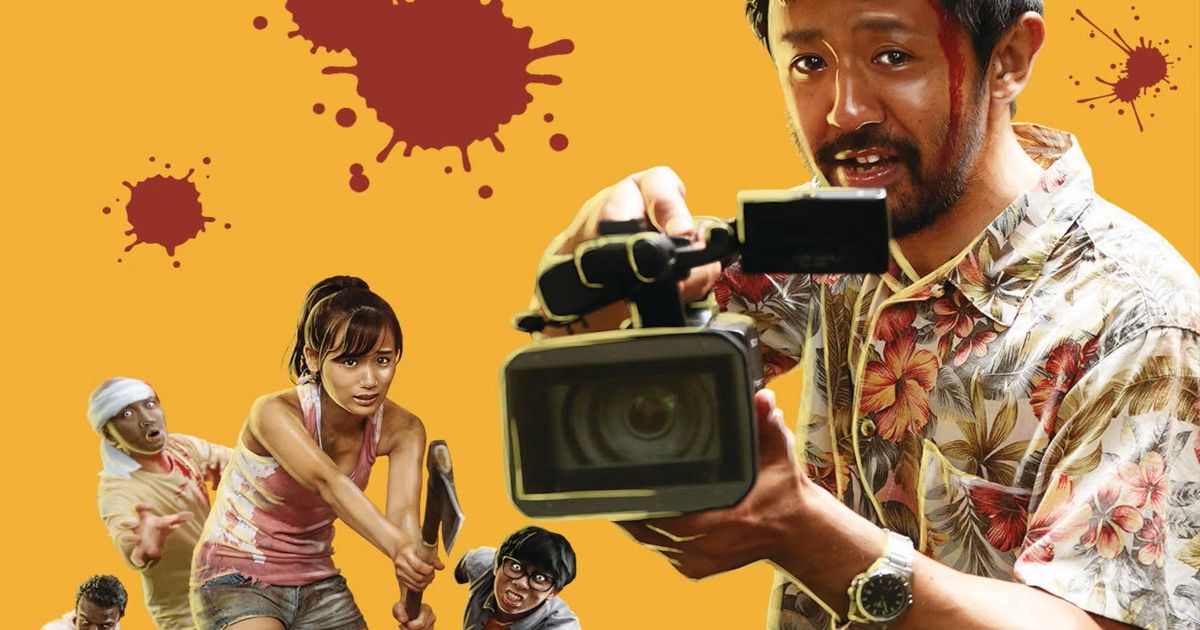

In 2011, Michel Hazanavicius won an Academy Award for Best Director for the Best Picture winner, The Artist. With that faux silent film, a decade before everyone called Parasite ‘the first international film to win Best Picture,’ the French BAFTA winner and perpetual Cannes darling arguably became one of the most acclaimed and successful international auteurs in the West. In the first minutes of his new film, Final Cut, a poorly painted blue zombie stalks an ax-wielding woman, before dismembered arms and decapitated heads fly about in a gory dance of schlock horror.

My, how times have changed.

Or have they? Before long, viewers realize that Final Cut is not the crude, low-budget zombie film it pretends to be for more than 30 minutes. No, Hazanavicius’ newly released film is not what it seems, not at all. In fact, the great French director has remade a brilliant Japanese film, One Cut of the Dead, and turned it into his most personal film, in the most metatextual way possible.

Final Cut follows a French director who is hired to remake a Japanese zombie project for French audiences, and is tasked with creating a live single take to launch a new horror channel, Z. The film he’s directing concerns a group of filmmakers and actors making a zombie movie, who are suddenly attacked by very real zombies. And so Final Cut is a nesting doll of artistry, a meta matryoshka of movie magic, a meditation on the artistic act, buried beneath layers of gross-out comedy, goofy gore, and gargantuan amounts of genuine passion. It’s one of the best films of the year.

Hazanavicius spoke with MovieWeb about Final Cut, the nature of remakes, and why this wacky horror comedy is his most personal film to date.

Anticipating Boos at Cannes

Final Cut, like One Cut of the Dead, takes the bold decision to begin with a film within a film for a roughly 35-minute long single take. Said film happens to be a schlocky horror movie, and it’s intentionally not well-made; additionally, with its crude gore and buckets of blood, Final Cut is hardly synonymous with the whole Cannes vibe. As such, Hazanavicius initially wondered whether critics and audiences would actually sit through his whole film when it opened the Cannes Film Festival back in 2022.

“I thought it was possible to be booed in the first 20 or 30 minutes. Because people at Cannes, they don’t know the original Japanese film. So if you know the movie, it’s okay, and you know where it’s going,” explained Hazanavicius, “but when you’re in Cannes, they’re very — in French, we say exigent, they want to see a certain kind of cinema, a certain kind of movie, and this is not really in that area […] And so I thought maybe they would think, ‘He doesn’t know how to make comedies anymore.'”

Fortunately, that wasn’t the case, even if “people were a little bit disturbed at the very beginning,” as Hazanavicius noted.

What Is a Remake?

If the Cannes audience (or viewers at home today) had seen One Cut of the Dead, they’d very much know what to expect. In fact, Final Cut is an extremely faithful remake, which may seem somewhat surprising for the iconoclastic French auteur. However, when studied comparatively, the two are somehow very distinct from each other.

Any adaptation is an independent creation; even if one were to use the exact same framing and mise en scène in a remake, the result will always be different (as Gus Van Sant proved in his shot-for-shot remake of Psycho). It’s as if, simply through the very contact of different people, the same source material can be molecularly rearranged. Hazanavicius had some poetic thoughts on this:

“I was offered to make a remake, and it was really close to what I wanted to do, but smarter and really funny. It was a beautiful playground for me. So at first, I started to work on a very French version, not a zombie movie, but a ‘French’ movie, with all the clichés of French cinema. But then I realized that I didn’t want to change just to change, and the energy of the zombie movie was really something very important to the craft of the movie. And I didn’t want to hide the original. I wanted to put it out in front and say, ‘This is a remake.’ And of course, I added some meta material, I added the musician, and some things here and there, and I think I made a French movie in the end.”

“But what I really discovered is that, even if you remake, you make a movie,” added Hazanavicius. “I think it’s a very personal movie, even though I don’t try to hide that it’s a remake or to kill the original. I wanted to respect it. I’ve been very faithful — everything I loved in the original, I took it and I kept it, but I changed what I wanted to change. And to me, the original is a real miracle, I still don’t know how they made it in six days with $25,000, it’s still an enigma for me.” Hazanavicius’ film had a budget of approximately $5 million in comparison. He continued:

But when you change the economy of the film in any way, it’s a translation. Even if you try to make more or less the same thing — where you put the camera, what you say to the actors, how you edit everything — this is your breath at the end, even if you adapt a book or a script written by someone else. In a way it’s close to what you’d do in stage plays. You do your own version.

Directing His Wife and Daughter, Bérénice Bejo and Simone Hazanavicius

Some of the many surprisingly personal elements of Final Cut — the French film director’s remake of the Japanese original follows a French film director (Romain Duris) remaking a Japanese zombie project; the director’s daughter (budding filmmaker Simone Hazanavicius) plays the on-screen director’s daughter, budding filmmaker Romy; the director’s wife (the great actor Bérénice Bejo) plays the on-screen director’s wife, also a great actor. It almost got more meta than that.

“During the prep, some people asked me, ‘Don’t you want to play the role [of the director]? I said, ‘No, I don’t,” smiled Hazanavicius. “It’s very difficult to direct this movie. It’s not an easy one, and I needed to be able to work with real actors, and good actors, and Romain Duris is a huge actor.”

Duris (The Confession, All the Money in the World, Eiffel) is astonishing in Final Cut, a live-wire ball of nerves stuck in an increasingly ridiculous cluster of chaos. It’s an interesting role to direct, since Duris is almost acting as Hazanavicius’ on-screen avatar. “I could see him, he was visually spying,” laughed Hazanavicius. “When I would do something like this [snaps fingers quickly], he was doing the same gesture that I would do.” Hazanavicius continued:

Do you know Michel Piccoli, the actor? He said the smartest thing I’ve heard about an actor. He said, “When I don’t know what to play, I play the director.” And that’s true, when you look at Le Mepris [Contempt], the Jean-Luc Godard movie, he plays Godard.

Michel Hazanavicius Makes His First Film — Again

Was all this meta-modern subtext ever too much for the director? Never. “Well, I love movies about movies. Of course, Day for Night, the Minnelli movies with Kirk Douglas [Two Weeks in Another Town, The Bad and the Beautiful], The Player,” listed Hazanavicius, a voracious consumer of cinema himself. That appetite and love for filmmaking is present in nearly all of his films, from the more explicit movies about movies (The Artist, Le Redoutable, and now Final Cut) to his more playful homages to genre filmmaking (the OSS 117 films, The Lost Prince).

“It’s often a pleasure for me to watch movies about movies. But there was something special on this one, because it was after lockdown,” explained the director, who burst out of quarantine with a passion for Final Cut. “So we were really like kids going out of school, like the first day of vacation. And that was really good, because that’s really something that I was afraid to lose, because I was changing economies, to working with professional technicians, commercial actors.”

In many ways, that’s what Final Cut is all about — a filmmaker rediscovering that his creative passion doesn’t need to be subjugated by the purely economic aspects of the business. “I didn’t want to lose that very special energy of the original. It’s really like a ‘first movie’ energy. And thanks to the end of the lockdown, we were so happy to be on the set. And also because we rehearsed the one-shot for five weeks with the actors. That created something close to what you can have on stage, with all the risks, so we had that special energy.”

All of that energy is on the screen in Final Cut, one of the best films released this year. From Kino Lorber, Final Cut is now in theaters.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Education News Click Here