You might not know Phil Tippett, but you know his work. The Oscar-winning artist behind the effects of numerous iconic scenes in films such as The Empire Strikes Back, Dragonslayer, Return of the Jedi, Robocop, Jurassic Park, and Starship Troopers has been working in the film industry for nearly half a century. Crafting creatures as disparate as the weird aliens in Evolution are from the Dark Overlord creatures in Howard the Duck, Tippett is a master of practical effects.

However, in between his work on these films and heading departments in George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic and the Lucasfilm creature shop for Star Wars, Tippett spent 30 years developing and devising what will surely be known as one of the most uniquely disturbing and frighteningly brilliant films of this decade, Mad God (coming to Shudder on June 16th). A far cry from the tauntauns and AT-AT Imperial Walkers that Tippett created, Mad God is an utter nightmare, a hellish but philosophically realistic and intense experimental film that must be seen to be believed. Watching it is certainly a powerful experience, but making it was more so, causing a breakdown and briefly sending Tippett to a mental institution. MovieWeb spoke with Tippett about his process and incredible career.

Tippett Goes From Special Effects God to Mad God

Before the big CGI craze was initiated in the ’90s, Tippett was a go-to artist for directors who were looking to expand the boundaries of great special effects, such as Lucas, Spielberg, and Verhoeven. Tippett has called his work here a ‘day job,’ but he clarifies. “It wasn’t a day job in a negative sense. I mean, ever since I could pick up a crayon, I was drawing spaceships, and monsters, and robots, and you know, it was always a lot of blood-red crayons. So that was just my thing, that I was interested in horror and sci-fi.”

His imaginative and meticulously detailed designs were a boon to filmmakers and studios looking to build worlds and evoke the kind of awe that classic Hollywood magic could deliver for people like Tippett. “When I was able to participate in all of that, it was in old Hollywood, where a lot of the stages and whatnot that we worked in were from the ’20s and ’30s and ’40s, you know, and I was just in pig heaven. It was everything that I had dreamed of, and I got to participate in them, and then Star Wars happened and everything just took off. So I was very happy to do that until, you know, Starship Troopers, and then I was not happy anymore, because everything has gotten so corporatized.”

Studio intervention, the rise of CGI, and the seemingly endless bureaucratic process in filmmaking began to hamper Tippett’s creativity. Mad God then became a kind of passion project, a burning desire in fits and starts, that would have never been made in the studio system. “There’s no way I could pitch Mad God to a studio. I couldn’t even pitch it to myself, you know, I just kind of waded into the deep end and just tried not to sink to the bottom of the pool.”

Defining the Undefinable in Mad God

Mad God certainly is like a descent, a caliginous abyss one could sink into, and Tippett definitely did. The film is difficult to describe, and it might be dangerous to do so; as director David Lynch once told Dennis Lim, recounted in The New Yorker, “As soon as you put things in words, no one ever sees the film the same way. And that’s what I hate, you know. Talking — it’s real dangerous.” There are labels that could be attached to Mad God, suitable terms for our buzzword society, such as ‘apocalyptic’ or ‘horror,’ but the film is ultimately more akin to the kind of great modern and postmodern art that never admits what it is, art which refuses any confession and simply is something one can peer into and project onto.

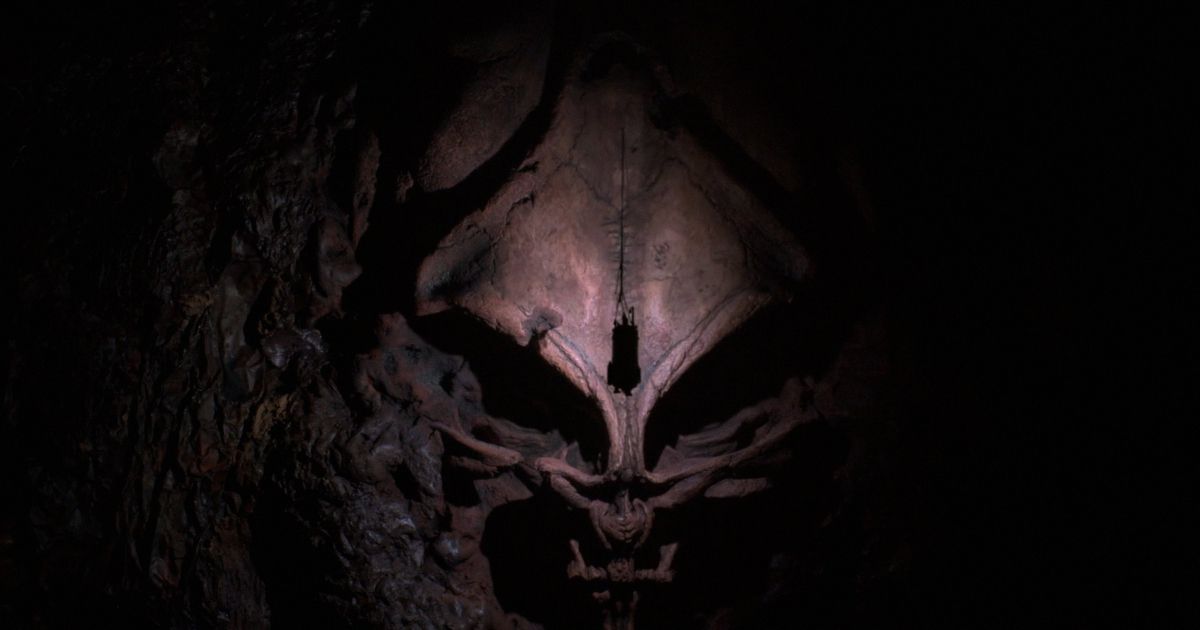

As such, one could call Mad God an avant-garde, aesthetic experience; it has almost no dialogue, and follows a kind of stream-of-consciousness through every layer of hell, mixing go-motion with some live-action, with miniature sets and creature design where everything is carefully made by hand. A man known as The Assassin wades down into the deep through a diving bell, taking an explosive device through a disgusting world of death and filth. The only thing on the horizon here is pain, suffering, and mushroom clouds.

Imaginatively designed, demonic-looking creatures appear in this ruinous city, and faceless charred bodies (looking like Giacometti sculptures) toil away in seeming slavery, randomly killed by the indifferent happenstance of a chaotic cosmos. War seems ubiquitous, and if anybody is overseeing the madness, they are not benevolent but just some bigger monster than us. What it all means (not that anything has to ‘mean’ anything) is up for debate, but what it feels like is disturbingly direct.

Tippett would probably agree with not wanting to classify or describe Mad God, though, saying, “My intention was just to make something like any art, where people project into it. I mean, tell me what the meaning of a Reinhardt or a Mark Rothko is, you know, good luck […] You can’t put a name to it, you know, good luck. Critics try, and it’s all just a bunch of nonsense, really. I don’t know one artist that looks through reviews and goes like, ‘oh, that’s totally it!’ I don’t read those things, you know?”

Phil Tippett on the Psychosis of Society

The great artist does take a minute to surprisingly elaborate on his thoughts, however, providing some invaluable insight into his thought process and reflections on his philosophical prism. Tippett explains:

I was very inspired at a young age by Hieronymus Bosch, and his work is, you know, simultaneously horrific and beautiful. And I sit out at the backyard with a cup of coffee and a cigarette, and I look at the moon through the trees and go like, “what’s the matter with these sons of bitches down here on Earth?” It’s all the old territorial imperative, you know, there’s so many of us that we’re crowding each other out. And, as a result of the media, [we’re experiencing] induced psychosis that’s very similar to schizophrenia. Look at, for instance, Ukraine. You see on the news, a bunch of bombed out cities, and one bombed out city is just like the next, you know, it’s just a bunch of junk. But you see it every night, over and over and over, but it’s not the same image. It’s just a different pile of junk.

And when you look at the World Trade Center going down, and you have the media chronicle that over and over and over and over, and it’s such an iconic image that it sticks in your mind as a ‘thing.’ It’s like watching a sculpture, you know, being destroyed. And I am convinced, and I’ve talked to other philosophers and psychiatrists that this does induce a psychosis, [one] that we see with these recent shootings in the US, so that’s the zeitgeist of the world we all live in. I mean, there was no avoiding it. I live in a beautiful place in a horrible place. And I didn’t I didn’t have to think about it much [to make Mad God].

Mad God is getting excellent reviews, with Sight and Sound calling it “an instant cult classic” for good reason. Every second of the film is pure Tippett, tapping into the darkest recesses of himself and the great hallucinatory masterpieces of visionaries like John Milton, Heironymous Bosch, and William Blake. Tippett has a brilliant mind, but a suffering spirit (the two of which often go hand in hand). The lengthy production of Mad God, a lot of which was funded by Kickstarter after almost two decades of on-and-off work, took its toll on Tippett’s mental health.

Mad God Caused Tippett a Breakdown

“I kind of became a method director and I just got totally lost. I hated working on it, and I just went down a rat hole of a psychic breakdown,” Tippett told The Guardian. “It was like an Arctic expedition,” he tells us, referring to the process of delving into the unknown and having it take him to places of great darkness. He often calls art a kind of exploration, but what he discovered in the expedition of Mad God seems to be a deeper (and somehow more refined) misanthropy and pessimism, the kind elaborated on in his beautifully bleak and gorgeously grotesque film.

While making Mad God was a confirmation of different beliefs, it also gave Tippett to do what he loves and does best: create, but for himself this time. “I think it was an indication of what I had already known, and it just substantiated what I knew about the process of making things that didn’t have an agenda or polemic to it. I mean, it’s like the Verhoeven line, ‘Who do you make your movies for?’ For instance, I make them for myself, you know, I don’t care what you think.”

Nonetheless, there’s a good audience for Tippett’s work, as evidenced by his successful Kickstarter which raised three times its stated goal. It seems that many people wanted Tippett to make Mad God for himself, with the results satisfying many. Considering that this project has been ongoing ever since the days of Robocop 2 in the early ’90s, there’s a possibility that Mad God could almost never end; it could just keep descending, deeper down that rat hole of madness Tippett spoke of.

Mad God is on Shudder, But Art is Never Finished

“No,” Tippett says, saying that art is probably never ‘done,’ it just “has to be taken away from you. It’s premiering on Shudder, and so it had to get locked.” Tippett continues:

We were always coming up with, you know, “we should do this better, we should do that.” There’s always one more thing, you know, but the door closed, and they just said, “No, that was that,” and it gets taken away from you. But thankfully, because it would just go on forever […] It was a chapter in my life I’m happy to have closed, and I want to go on to other things. I want to do kind of a sequel to Mad God called Pequin’s Pendiquen, where Pequin is the main character, but it’s a lot lighter, you know? Because I gotta get money and a crew, so, you know, it’ll be commercial.

Fortunately, Tippett’s definition of commercial is probably the majority’s version of experimental, and he seems incapable of creating something bland and bad, even if it kills him in the process. Mad God is streaming exclusively on Shudder beginning June 16th.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Education News Click Here