Forty-five years after his death, Elvis is back. Played by 30-year-old Austin Butler in Baz Luhrmann’s riot of a biopic, the young king of rock ’n’ roll is transformed into an ethereal dandy.

Elvis wears black-lace shirts beneath baby-pink suits, and a quiff that grows bigger and bouncier the more money he makes. “I cannot overstate how strange he looked,” muses his manager Colonel Tom Parker, played by Tom Hanks with a mixture of showman’s verve and quiet menace, as he recalls his first encounter with his prodigy.

Luhrmann’s film, in UK cinemas later this month, is long. At two hours and 39 minutes, it has to work hard to keep the audience’s attention — and it succeeds, thanks in part to a parade of exuberant costumes.

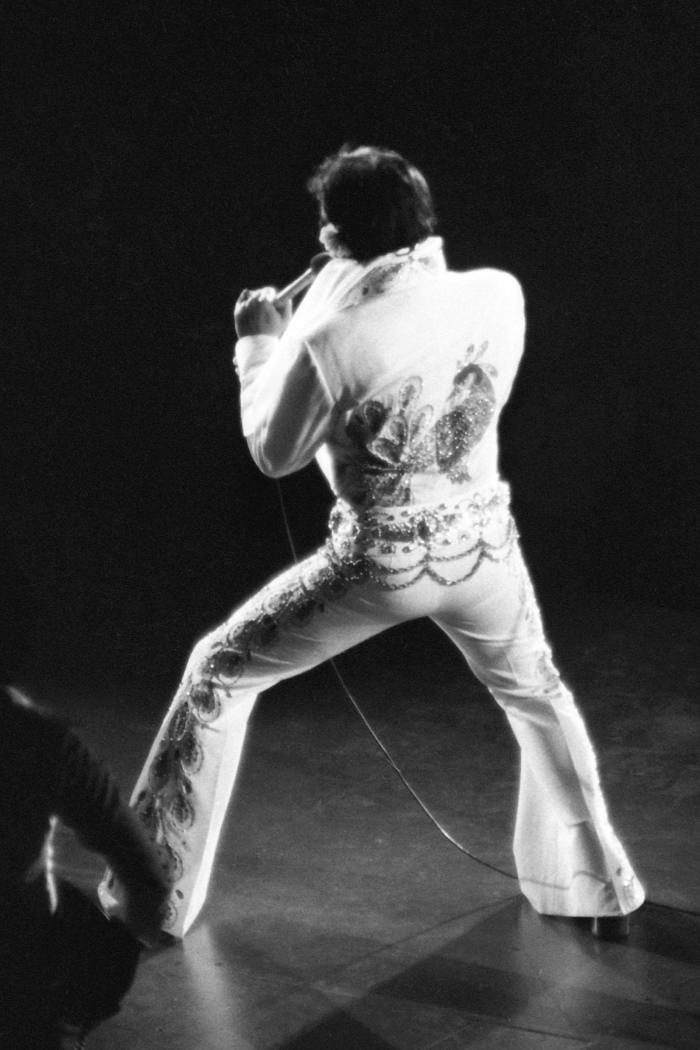

Butler is on screen almost constantly, playing Elvis from his early-1950s-style epiphany outside his local tailors, Lansky Bros of Beale Street, Memphis, to the jumpsuit years and the overwrought Vegas shows of the 1970s.

How many costume changes does Butler go through? “I think it’s 93 . . . definitely over 90,” says Catherine Martin, the film’s costume designer, co-producer and Luhrmann’s longtime creative collaborator and wife, in a call.

The film spans more than three decades — the postwar era when fashion changed at dizzying speed. Some ensembles were imagined and created to fit the plot; others were replicas of outfits Elvis and other main characters really wore.

Martin says the hardest challenge was dressing Butler for the moment Elvis became a star: “Finding that 1950s look that encapsulated Elvis’s rebelliousness and sexuality at that watershed moment — and then allowing Austin’s performance to fit his version of Elvis, rather than slavishly copying the originals.”

Martin — a warm, exuberant Australian — is a four-time Oscar winner for her work on previous Luhrmann films, including The Great Gatsby and Moulin Rouge! She says she and Luhrmann pored over film, fan footage, photographs and archives to nail the spirit of the characters and their era.

Sometimes, her costumes function like a supporting cast, in that they often seem to be symbolic. For example, Elvis’s baby-pink and powder-blue suits worn with black-lace shirts in early scenes evoke innocence on the outside and sexuality within. Martin says they were largely imagined: “It was about using colours that were characteristic of male tailoring at that time, and combining it with the sexy and subversive.”

Others are eerie coincidences. In a later scene at the end of their marriage, Elvis’s wife Priscilla, played by Olivia DeJonge, wears a patchwork coat — suggesting the patching of a disintegrating marriage.

In fact, says Martin, DeJonge’s coat is a replica of one worn by Priscilla when she and Elvis emerged arm in arm from the divorce court in Los Angeles in 1973.

In his final concert scene, a frail Elvis performs “Unchained Melody” wearing a jumpsuit emblazoned with a golden sun — America’s golden son — and an upside-down horseshoe pendant that suggests his luck is draining away. The golden-sun jumpsuit is a replica of one worn on stage by Elvis in his last performance in Indianapolis in 1977, two months before his death.

“Who knows what was going on in his mind? Elvis had lots of superstitions, and he took signs and symbols very seriously,” says Martin. “For example, he felt peacocks were auspicious because his 1968 NBC Comeback Special was so successful, and the NBC logo was a peacock tail feather. Later, he often wore a peacock-embroidered jumpsuit.”

That televised concert was crucial in restoring Elvis’s career — the moment he reclaimed his crown. Until then, a decade after his heyday, he had been largely written off after a series of mostly dreadful film roles and lacklustre releases.

For the ’68 Comeback Special scene Butler wears a replica of Elvis’s slim, black-leather ensemble, worn with Napoleon collar and necktie: the black leather made the King stand out against a flower-power, psychedelia-era audience.

Martin points out that Elvis’s clothes were usually his own choice, and his instincts were strong: “Stylists are a very modern concept. He worked with designers, but he was his own maker of style. He really made it happen for himself.”

But she credits the celebrated Hollywood costume designer Bill Belew for that leather ensemble — he was the man who would go on to dress Elvis in a blur of bejewelled jumpsuits and capes in the Vegas years. They not only shimmered like the Vegas Strip at night; they accommodated his increasing girth and his favoured kung-fu-style stage moves. The film’s jumpsuit creations were hand-embroidered by Gene Doucette, who worked on Elvis’s originals.

Women’s costumes are just as lavish and considered as Elvis’s stage gear. The Sweet Inspirations, Elvis’s onstage backing group, wear immaculate matching ensembles with long tassels hanging from sleeves that emphasise their movements.

Elvis’s mother Gladys, played by Helen Thomson, goes from downtrodden drudge to elegant mistress of Graceland, Elvis’s Memphis mansion, as her son becomes very rich, very quickly. In a tender scene after Gladys’s death in 1958, a distraught Elvis is seen caressing the clothes in her wardrobe.

Martin and her team drew on Gladys’s clothes still held in Memphis by archivists at Graceland. “We opened a box of Gladys’s clothes and we felt the sadness lift off those garments,” she says. “The sadness of an unfulfilled existence.” Gladys died young, in her mid-forties and at the height of her son’s first rush of fame.

Priscilla Presley, Elvis’s former wife, now 77, offered styling advice to DeJonge, who as Priscilla wears a series of spectacular beehives that grow more elaborate as her marriage progresses. Like the patchwork coat, Priscilla’s wedding dress was a facsimile of the original.

Other DeJonge costumes were interpretations. Martin’s team worked with longstanding collaborator Miuccia Prada and Prada’s team of expert craftspeople — the Italian designer, says Martin, is “always referring to the past, but always with an eye to the future”. Their creative challenge was: “How do we connect a modern audience to Priscilla’s revolutionary style?”

For some costumes Martin considered Priscilla’s original wardrobe, then went through Prada’s archives to find pieces that related to her innate style. They were then custom made for DeJonge. Here, Prada’s expertise was invaluable: “Shoemaking, embroidering, beading — all of that brings so much value,” says Martin.

Elvis took more than a year to film (partly delayed by the pandemic). As well as specially commissioned items, costumes were purchased from collections, hired from Europe and the US and sourced from vintage dealers. In an early scene, when the not-quite-famous Elvis takes to the stage in a pink suit in a segregated southern US town, his quivering, pouting hip-swivelling sends his teenage audience into a state of delirium. They clutch at their faces and tear at his clothes. A prim girl emits an involuntary scream, as if possessed by a force greater than herself.

And, of course, she is, because the world has changed for ever. The opulent costumes in this cinematic portrait remind us that Elvis was more than a performer; he embodied a moment in time.

Follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here