The privacy invasion was vast when FBI agents drilled and pried their way into 1,400 safe-deposit boxes at the U.S. Private Vaults store in Beverly Hills.

They rummaged through personal belongings of a jazz saxophone player, an interior designer, a retired doctor, a flooring contractor, two Century City lawyers and hundreds of others.

Agents took photos and videos of pay stubs, password lists, credit cards, a prenuptial agreement, immigration and vaccination records, bank statements, heirlooms and a will, court records show. In one box, agents found cremated human remains.

Eighteen months later, newly unsealed court documents show that the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles got their warrant for that raid by misleading the judge who approved it.

They omitted from their warrant request a central part of the FBI’s plan: Permanent confiscation of everything inside every box containing at least $5,000 in cash or goods, a senior FBI agent recently testified.

The FBI’s justification for the dragnet forfeiture was its presumption that hundreds of unknown box holders were all storing assets somehow tied to unknown crimes, court records show.

It took five days for scores of agents to fill their evidence bags with the bounty: More than $86 million in cash and a bonanza of gold, silver, rare coins, gem-studded jewelry and enough Rolex and Cartier watches to stock a boutique.

The U.S. attorney’s office has tried to block public disclosure of court papers that laid bare the government’s deception, but a judge rejected its request to keep them under seal.

The failure to disclose the confiscation plan in the warrant request came to light in FBI documents and depositions of agents in a class-action lawsuit by box holders who say the raid violated their rights.

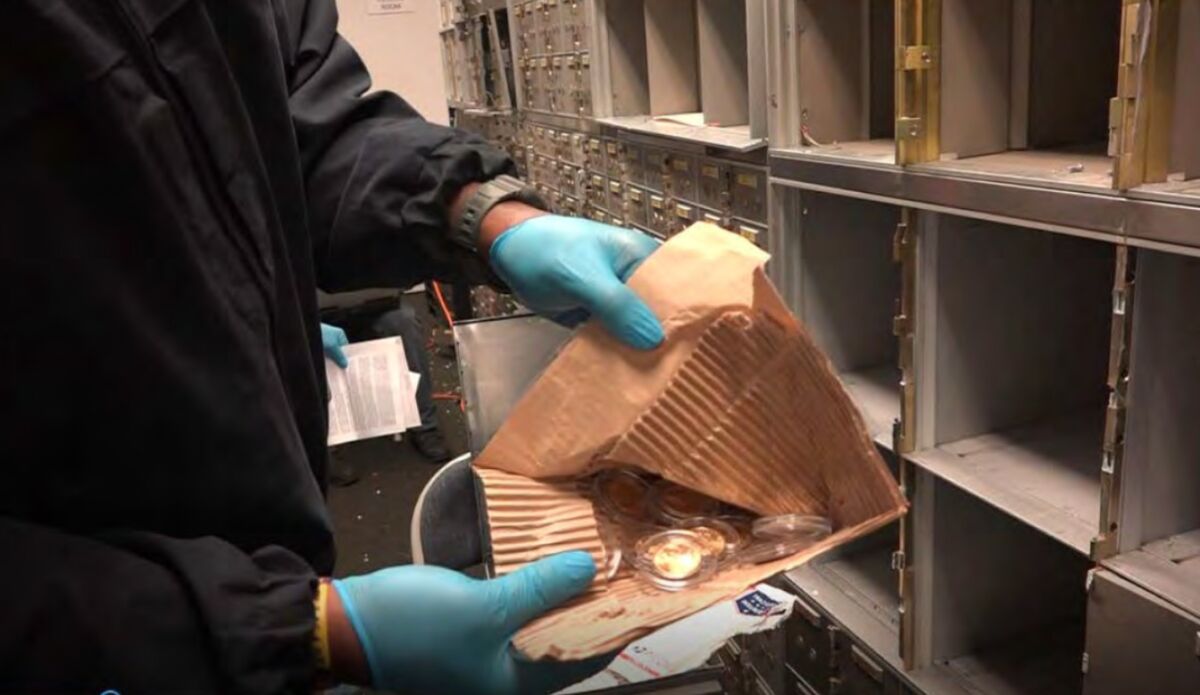

FBI agents search safe-deposit boxes during at the U.S. Private Vaults store in Beverly Hills, shown in a video screen capture taken from U.S. District Court records.

(U.S. District Court)

The court filings also show that federal agents defied restrictions that U.S. Magistrate Judge Steve Kim set in the warrant by searching through box holders’ belongings for evidence of crimes.

“The government did not know what was in those boxes, who owned them, or what, if anything, those people had done,” Robert Frommer, a lawyer who represents nearly 400 box holders in the class-action case, wrote in court papers.

“That’s why the warrant application did not even attempt to argue there was probable cause to seize and forfeit box renters’ property.”

After a two-year investigation that opened in 2019, leaders of the FBI’s Los Angeles office believed U.S. Private Vaults was a magnet for criminals hiding illicit proceeds in their boxes.

The business was charged with conspiracy to sell drugs and launder money.

The FBI and U.S. attorney’s office denied that they misled the judge or ignored his conditions, saying they had no obligation to tell him of the plan for indiscriminate confiscations on the blanket assumption that every customer was hiding crime-tainted assets.

FBI spokeswoman Laura Eimiller said the warrants were lawfully executed “based on allegations of widespread criminal wrongdoing.”

“At no time was a magistrate misled as to the probable cause used to obtain the warrants,” she said.

U.S. Private Vaults has pleaded guilty to conspiracy to launder drug money, and the investigation is continuing, she said.

The plaintiffs in the class-action suit have asked U.S. District Judge R. Gary Klausner to declare the raid unconstitutional. If he grants the request, it could force the FBI to return millions of dollars to box holders whose assets it has tried to confiscate.

It could also spoil an unknown number of criminal investigations by blocking prosecutors from using any evidence or information acquired in the raid, including guns and drugs.

Until the FBI shut it down, U.S. Private Vaults was an easy-to-miss store in an Olympic Boulevard strip mall with a Supercuts hair salon and kosher vegan Thai restaurant.

Around 2015, it began attracting police attention. Local detectives and federal agents spotted drug suspects walking in and out.

The U.S. Private Vaults store in a strip mall on Olympic Boulevard in Beverly Hills.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

FBI agent Lynne Zellhart, a former Sacramento attorney, first heard about it from a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy. Customers, who could rent boxes without identifying themselves, entered the store’s vault with a biometric eye scan, the deputy told her.

The Sheriff’s Department suspected a customer was a criminal but was “having all kinds of problems getting into the box that they had a warrant for because of the nature of the business,” Zellhart testified in the class-action suit.

By 2019, federal and local law enforcement had managed to search more than a dozen boxes and seized about $5 million from five drug dealers, a bookie and a debit card thief.

The FBI opened an investigation of the business itself. Zellhart, who specializes in money laundering, said she thought it should be shut down. She joined forces with counterparts at the Drug Enforcement Administration and Postal Inspection Service.

Through surveillance, informants and undercover work, they surmised that U.S. Private Vaults and a precious-metals store next door were helping drug dealers launder cash by converting it into gold and silver they stashed in their boxes.

Zellhart was tasked with spelling out the government’s case in an affidavit that took her more than six months to write. Prosecutors submitted it to Kim in a request for six warrants.

Five of them were for straightforward searches of the store and the homes of its owners and managers to gather evidence for prosecution of the company.

But the sixth — to seize the store’s business equipment for forfeiture — was highly unusual. The government wanted to take not just computers, money counters, video cameras and iris scanners, but also the “nests of safety deposit boxes and keys.”

The only way the FBI could seize the racks of boxes would be to take possession of the contents too. Any judge reviewing the warrant request would recognize a threat to the rights of what turned out to be about 700 customers who had locked away some of their most private and valuable belongings.

Box holders would liken the raid to police barging into a building’s 700 apartments and taking every tenant’s possessions when they have evidence of wrongdoing by nobody but the landlord.

A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office declined to say whether the government had evidence of criminal activity by any specific box holders prior to the raid.

An FBI agent inspects the contents of a safe-deposit box during the raid of U.S. Private Vaults in this video screen-capture taken from U.S. District Court documents.

(U.S. District Court)

The Fourth Amendment protects people against “unreasonable searches and seizures.” It requires the government to get a warrant by showing in a sworn statement that it has probable cause to believe that a particular place needs to be searched and describing specific people or things to be seized.

In her affidavit, Zellhart made sweeping allegations of criminal wrongdoing by box holders, saying it would be “irrational” for anyone who wasn’t a lawbreaker to entrust the store with assets that a bank could better safeguard.

“Only those who wish to hide their wealth from the DEA, IRS, or creditors would” rent a box anonymously at U.S. Private Vaults, she wrote.

But the FBI’s evidence against customers was thin.

Agents had seen some of them pull up to the store in vehicles with Nevada, Ohio and Illinois license plates, Zellhart wrote.

“Based on my training and experience in money laundering investigations, Chicago, Illinois is a hub of both drug trafficking and money laundering,” she said. “I believe these patrons were using their USPV box to store drug proceeds.” She cited no facts to back up the suspicion.

Other customers were showing up in rental cars, and that too, she claimed, was a sign of drug dealers evading law enforcement. An owner of U.S. Private Vaults told a government witness that the store’s best customers were “bookies, prostitutes and weed guys,” Zellhart wrote.

Of all the box holders, Zellhart mentioned only nine, either identifying them by their initials or not at all. She said they were “linked” or “associated” with law enforcement investigations, but again provided no facts specifying criminal misconduct.

While the majority of customers seemed to be drug dealers, she wrote, U.S. Private Vaults tried “to attract a non-criminal clientele as well, so as not to be too obvious a haven for criminals.”

At Zellhart’s deposition, Frommer asked, “Was it your opinion that most of the people who rented safe-deposit boxes were criminals in some way?”

“I was expecting a lot of criminals,” she said. “I don’t know about most.”

Frommer reminded her of the language in her affidavit.

“I don’t sort of know how to answer your question as to whether it was all of them, it was most of them,” she responded. “I don’t — I don’t have a percentage.”

Attorney Robert Frommer, left, with his clients Jennifer Snitko, her husband Paul Snitko, far right, and Joseph Ruiz, who are plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit over the FBI raid of U.S. Private Vaults.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

On the affidavit’s 84th and 85th pages, Zellhart assured Kim the FBI would respect customers’ rights.

That section, she testified, was written by Andrew Brown, an assistant U.S. attorney and driving force of the investigation.

What Brown wrote contradicts the FBI’s plan for hundreds of box confiscations. He underlined the government’s lack of evidence to justify any criminal search of the customers’ property.

“The warrants authorize the seizure of the nests of the boxes themselves, not their contents,” his section of the affidavit said. “By seizing the nests of safety deposit boxes themselves, the government will necessarily end up with custody of what is inside those boxes initially.”

The affidavit told Kim that agents would “follow their written inventory policies” and “attempt to notify the lawful owners of the property stored in the boxes how to claim their property.”

Under FBI policy, it said, inspection of each box would “extend no further than necessary to determine ownership.” But agents’ inspection of the boxes went substantially further — just as the government planned, according to FBI records filed in court.

By the time Kim got the warrant request, the FBI had been preparing an enormous forfeiture operation for at least six months, according to Jessie Murray, the chief of the FBI’s asset forfeiture unit in Los Angeles.

In the summer of 2020, she testified, Matthew Moon, then one of the highest-ranking FBI agents in Los Angeles, asked her if her team “was capable of handling a possible large-scale seizure” of safe-deposit boxes at U.S. Private Vaults.

Murray told him yes. She recalled joining a conference call in late 2020 and another in early 2021 to plan forfeitures of the box contents with the U.S. attorney’s office, other federal and local agencies, and “maybe even our legal forfeiture unit at [FBI] headquarters in D.C.”

Zellhart and a colleague confirmed the grand scale of the planned forfeiture in a memo to fellow agents with detailed instructions for carrying out the raid.

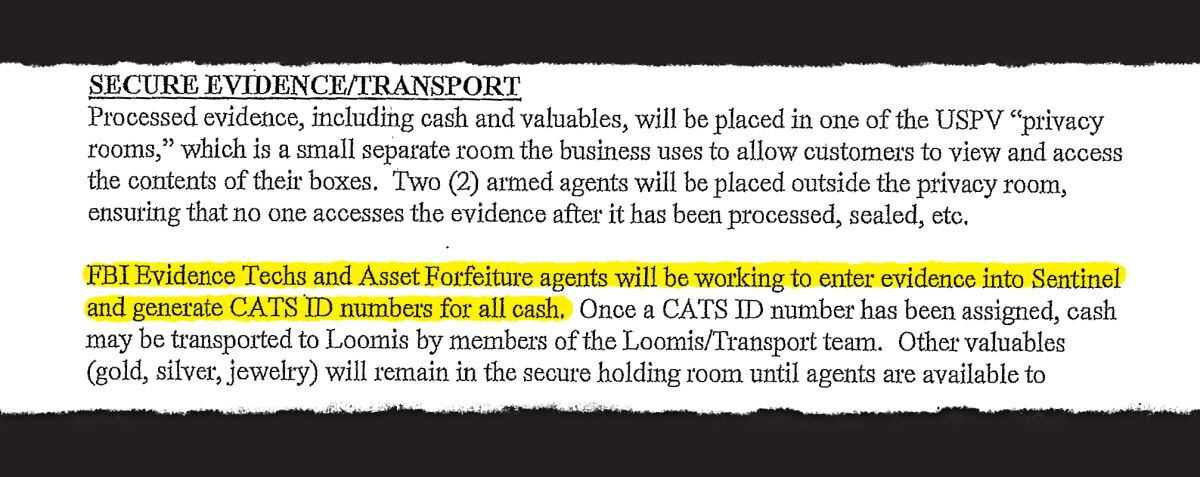

The memo, approved by Moon and two other senior FBI managers, ordered agents to assign “CATS ID” numbers to “all cash” found in the boxes. The government uses the Consolidated Asset Tracking System to keep track of everything it seizes for forfeiture.

Murray testified that once she reviewed the final draft of Zellhart’s affidavit, it was clear to her that there was probable cause to seize and confiscate the contents of every box — as long as it met the $5,000 minimum set by the Justice Department’s Asset Forfeiture Policy Manual.

Murray offered no explanation for why the FBI believed it had legal grounds to take away the assets of hundreds of unknown box holders based on their presumed ties to unknown crimes.

To confiscate an asset under U.S. forfeiture laws, the government must first have evidence that it was derived from criminal conduct or used to facilitate it.

This excerpt from the FBI’s plan for the raid on U.S. Private Vaults instructs agents to assign forfeiture identification numbers to “all cash” found in the safe-deposit boxes so the money could be permanently confiscated on the presumption it was linked to crime.

In a court filing in the class-action case, Brown and other prosecutors claimed the FBI had no obligation to tell Kim that it was “prepared to seek forfeiture” of property inside the boxes.

Agents “owe a duty of candor to courts,” they acknowledged, “but that is about known facts that have already occurred.”

They said the FBI did not need to tell Kim “how later actions, such as criminal investigations against boxholders or forfeiture of box contents, would play out.”

Kim was explicit in limiting the scope of the raid. “This warrant does not authorize a criminal search or seizure of the contents of the safety deposit boxes,” his warrant stated.

The judge gave the FBI permission to take inventory of the box contents to protect against theft accusations. He ordered agents to identify the owners and notify them that they could claim their property.

But by then, Zellhart and her colleague had already told agents in their memo to take notes on anything that suggests any of the cash “may be criminal proceeds,” such as whether it was bundled in rubber bands or smelled like marijuana.

The FBI also had dogs sniff all the cash for any odor of marijuana or other drugs, a step that was outside the bounds of the “written inventory policies” that the government vowed to follow.

Lyndon Versoza, a postal inspector who often has dogs check mail for drug investigations, testified that Zellhart or a DEA agent — he could not remember which — asked him to round up K-9 teams. He got dogs from the Glendale, El Monte, Chino and Los Angeles police departments to smell the money.

At his deposition, Versoza was asked whether a drug dog can help identify the owner of a pile of cash.

“No,” he responded.

What about protecting agents against accusations of theft, Frommer asked.

“No,” Versoza said.

Could a dog help justify forfeiture of the cash?

“It could,” Versoza replied.

Prosecutors have made extensive use of the dog alerts on cash — notoriously unreliable evidence in a state where marijuana is legal — to convince judges to approve confiscation of box holders’ money.

In the raid’s aftermath, the criminal case against U.S. Private Vaults sputtered to an end with nobody sent to prison.

The company went out of business. It was sentenced to pay a $1.1-million fine for laundering drug money, but prosecutors conceded it lacked the means to pay it.

Under a plea deal, the U.S. attorney’s office agreed not to prosecute the company’s owners, despite a Justice Department policy under Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland to hold individuals accountable for corporate wrongdoing — and despite Zellhart telling Kim it was “owned and managed by criminals.”

The FBI and U.S. attorney’s office rebuffed repeated Times requests for a full accounting of what was seized. They divulged neither how much the government has kept, nor how much it has returned.

Records from dozens of lawsuits stemming from the raid make clear, though, that it produced a windfall of tens of millions of dollars for the Justice Department. Local police departments that assisted in the raid have sought shares of the money, according to Murray.

Some of the government’s gains came from customers who abandoned their boxes. “There’s a good number of people who just said, ‘I don’t want it,’ ” Zellhart testified. “I think there was 20 or 30 of those.”

When the FBI vacated U.S. Private Vaults, it posted a notice in the store window inviting customers to claim their property. The FBI went on to investigate anyone who stepped forward, checking their bank records, state tax returns, DMV files and criminal histories, agents testified.

A sign taped on the window of U.S. Private Vaults in Beverly Hills advises people whose valuables were seized by federal agents to contact the FBI to retrieve them.

(Joel Rubin / Los Angeles Times)

Lawyers for box holders denounced the process as a ploy to gather evidence for forfeitures and criminal investigations.

Zellhart testified that the FBI was just making sure it was returning things to rightful owners.

In all, the FBI ultimately returned at least some of the contents of about 430 of the 700 boxes, according to the government.

Many box holders have agreed to give up a portion of their cash and property after deciding it was not worth spending tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees — or more — to recover the rest.

Some of those, and many others, have faced baseless FBI accusations of criminal wrongdoing. In May 2021, the FBI claimed the contents of 369 boxes — including the $86 million in cash — were linked to crime and filed papers for confiscation through forfeiture.

It went on to return everything in about 180 of those boxes after failing to produce evidence to support the allegations, court documents show. Those box holders retrieved more than $27 million. Attorneys for other customers say they recovered close to $25 million more through private negotiations with the U.S. attorney’s office.

“This entire episode is a stain on the U.S. attorney’s office and on everyone who played a part in it,” said Benjamin Gluck, a lawyer for box holders.

Prosecutors have pressed ahead, filing more than 40 court complaints to confiscate millions of dollars from box holders who challenged the seizures.

In some of those cases, prosecutors cited no evidence that the money was tied to any specific crime, alleging simply that a dog smelled drug residue on the cash, or that it was bagged or wrapped in a way that aroused suspicion of drug trafficking.

In a few other cases, prosecutors and the FBI accused box holders by name of committing multiple felonies, offered no evidence to back up the allegations, and then gave back everything.

One of those customers was a glassware maker who kept more than $340,000 in cash and gold in his box.

In a court declaration, he said he rented the box in 2020 because it was a “disturbing and scary” time of social upheaval, and he distrusted banks.

The U.S. Private Vaults store in Beverly Hills.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

“Protests and riots were the normal news, banks had been boarding up their windows, and emergency alerts were prompting people to stay indoors after curfew,” he wrote.

Prosecutors falsely accused the man of fraud, racketeering, conspiracy, drug trafficking and money laundering. FBI agent Madison MacDonald — who co-authored the raid plan — filed a sworn statement saying the allegations were true.

The complaint included no evidence the glassware maker had committed any of those crimes, but alleged he had “an extensive history of narcotic trafficking arrests and convictions.”

The man’s lawyer, Yael Tobi, castigated the prosecutors for exaggerating expunged misdemeanors, saying they intentionally omitted that he’d been arrested 16 years ago and was never convicted of a felony.

She called it “an egregious abuse of power.”

Spokespersons for both the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office declined to comment on the case.

Prosecutors demanded that the glass maker provide a sworn statement on when, why and from whom he received every dollar of the $340,000; the names of everyone who’d given him gifts since 2017; five years of tax returns for him and his wife, a doctor; and all of their bank and investment account numbers.

“Before proceeding too far down the road on this case, do you have a settlement offer to resolve this matter?” Assistant U.S. Atty. Victor Rodgers asked Tobi in an email six days later. “The government is prepared to be reasonable in connection with a resolution, and I think that an early settlement of this case would probably be beneficial to both parties.”

Tobi refused to cut a deal. She asked U.S. District Judge Mark C. Scarsi to “put a stop to the government’s abuse and overreach” by dismissing the complaint.

On March 9, nearly a year after the FBI seized the man’s cash and gold, Scarsi ordered the government to give it back.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Fashion News Click Here