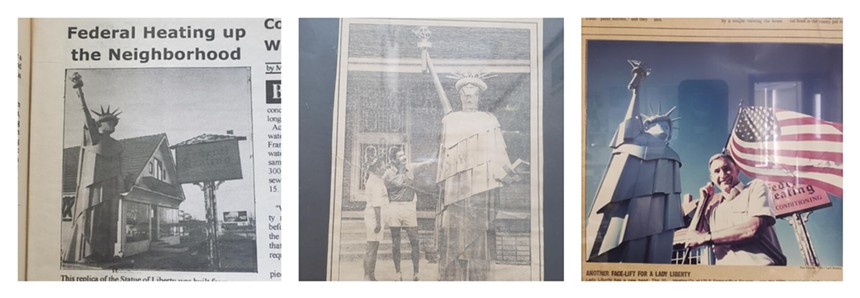

Since 1982, the handcrafted Statue of Liberty replica, which is more than ten feet in height and weighs hundreds of pounds, has guided customers to Federal Heating, at 175 South Federal Boulevard, even as it’s become a beloved icon for generations of area residents.

But now, Federal Heating, which owners (and siblings) Bo and Sherry Ramsour believe is the oldest heating, ventilation and air conditioning company in the state, is set to close after 84 years. And while there’s a chance the statue could remain on Federal even after the Ramsours shut the business down at the end of June, there are no guarantees. Bo says everything will depend on the property’s next owner, and there isn’t one yet.

Granted, the statue’s been through worse — including a decapitation. “Someone got a ladder and unscrewed her head off,” Bo says of the 1986 incident. “But the metal on top was so sharp that there was blood all over it.”

The Ramsours disagree about how the noggin and the body were brought back together. Bo thinks the head was returned after a few weeks, while Sherry has a more dramatic memory. “The way I heard it, the cops saw someone walking down Federal with it,” she recalls. “And they knew exactly where it came from.”

Federal Heating was founded in 1939, but its roots run even deeper into Denver history. “My great-uncle, Bert Ramsour, started it in a little house on South Newton Street,” Bo recounts. “But then it moved over to 175 South Federal, which was actually my grandmother’s house. She purchased it in 1911, when Federal Boulevard was a dirt road.” Additions were made to the structure as the business expanded.

Bo and Sherry’s late father, Bob Ramsour, who was born at the house that became his workplace, officially joined the Federal Heating fold after serving in the Navy during World War II, and his timing was ideal. In the late 1940s, “Public Service Company, which is now Xcel, started to bring natural gas into the west side of Denver,” Bo explains, “and they were overwhelmed having to convert all of these old furnaces from coal to natural gas. So they hired a few contractors to do these conversions, including my uncle and my dad.”

Bob Ramsour’s Uncle Sam sculpture was destroyed by vandals; a look at Federal Heating around the time of its 1939 founding.

Courtesy of Federal Heating

The gig turned into an even greater opportunity when Bert and Bob bought the rights to a device designed by a Public Service employee. “It was called a muckle burner,” Bo says. “It was a burner that had a little blower on it that would work on any house, whether it was 600 square feet or 5,000 square feet. They were extremely busy installing them, and some are still being used today. A few years ago, a guy came in needing a new motor for his, and we can still get them.”

In the early 1950s, Bob bought Federal Heating from Bert for a price that seems absurdly low by 2023 standards. “He paid $1,500, and that included the building and the truck,” Sherry says. By the end of the decade, Federal Heating had become a dealer for Lennox, which Bo calls “the Mercedes-Benz of furnaces,” but over time, it also began stocking parts for people with do-it-yourself skills.

By the early 1980s, when Bo came aboard full-time after earning a business degree from the University of Northern Colorado, the parts sideline had become the cornerstone of Federal Heating’s success, much to the chagrin of its rivals. “We got a lot of flak from our competitors and even from some of the manufacturers,” he recalls. “They would say, ‘You’re taking away from the install business.’ Our defense was that the type of people we were selling to weren’t going to do an install anyhow” — and if they got in over their heads, they’d call Federal Heating to fix things.

Sherry, who’s six years younger than Bo, wasn’t initially planning to make Federal Heating her career. “I’m a girly-girl,” she says. “I used to tell my dad, ‘Gas valves stink. There’s nothing glamorous about a gas valve. And what if I break a nail?'” But she ultimately made peace with the idea of dealing with “cranky old men,” becoming a parts pro in addition to organizing the operation and keeping the books.

Bob, meanwhile, carved out enough time from his busy schedule to indulge in his hobby. “My dad learned the sheet-metal trade,” Bo reveals. “He learned by reading geometry books and became an expert at crafting things — and every year, he’d make a sheet-metal figure. He made a skier skiing down the slopes, he made an Uncle Sam, he made a knight in shining armor, he made a Tin Man like the one in The Wizard of Oz, and he’d put them out front. People would drive by and take pictures. It was good advertising.”

Eventually, the collection of sculptures was placed on Federal Heating’s roof. But during the late 1970s, Sherry says, “somebody scaled the back of our building and threw all of them into the alley. So we don’t have them anymore, which is really sad.”

The vandalism didn’t prevent Bob from creating his masterpiece. “He decided he wanted to make the Statue of Liberty, and it was quite an undertaking,” Bo maintains. “He made drawings for about a year, and checked out books from the library to learn how the French erected the real statue — how they riveted structures inside, how they supported it.”

The project took two years or so, in part because Bob “was against buying new material,” Bo continues. “He wanted to use scrap metal, so whenever there was leftover metal from a job or a tear-out, he would take the metal home.”

The resulting structure grew so large that Bob couldn’t get it out of the garage of his southwest Denver house, where it was built, without partially disassembling it. But when the finished product was placed in front of Federal Heating, it quickly became a community landmark and earned numerous newspaper writeups — including coverage of the stolen head.

In 2017, nearly twenty years after Bob formally passed Federal Heating to Bo and Sherry, the statue faced another challenge, when the land on which it rests was taken over by eminent domain in order to widen Federal. But Bo says then-Denver City Council member Paul López, now the Denver Clerk and Recorder, came to the rescue: “He told us, ‘I remember seeing the statue when I’d drive by with my parents. We’re going to do what we need to do to save it.’ And they did.”

The current situation is more complicated. Sherry has experienced some recent health challenges, and the parts business has taken a hit from the internet, since people are able to order what they need online for less than they’d pay at Federal Heating.

Given these circumstances, Bo started looking for someone to take over the business a few years back, and when these efforts failed, he and Sherry decided to sell the property. At least two suitors are currently circling a sale, and one who’s signed a letter of intent has said he’d like to keep the statue. But nothing’s final, and the Ramsours have decided to turn out the lights by July 1 whether or not anyone’s bought the place.

As for the statue, Bo says, “If for some reason a new owner doesn’t want it, I’m going to make a base for it and put it in my front yard in Lakewood — if the city allows it.”

Lady Liberty is standing by.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest For Top Stories News Click Here