The photographer Diane Arbus had a phrase for the distinction between the way you think you appear and how you actually look: “The gap between intention and effect”. On one side lies pretence and projection; on the other, the inevitable but unintended slips. Now Gillian Wearing, Arbus’s self-anointed disciple and the subject of a hefty, sporadically transfixing mid-career retrospective at the Guggenheim, steers through the same narrows to a different conclusion. Arbus was interested in revelation. Wearing suggests that behind each mask lie more masks — that even confession is an act.

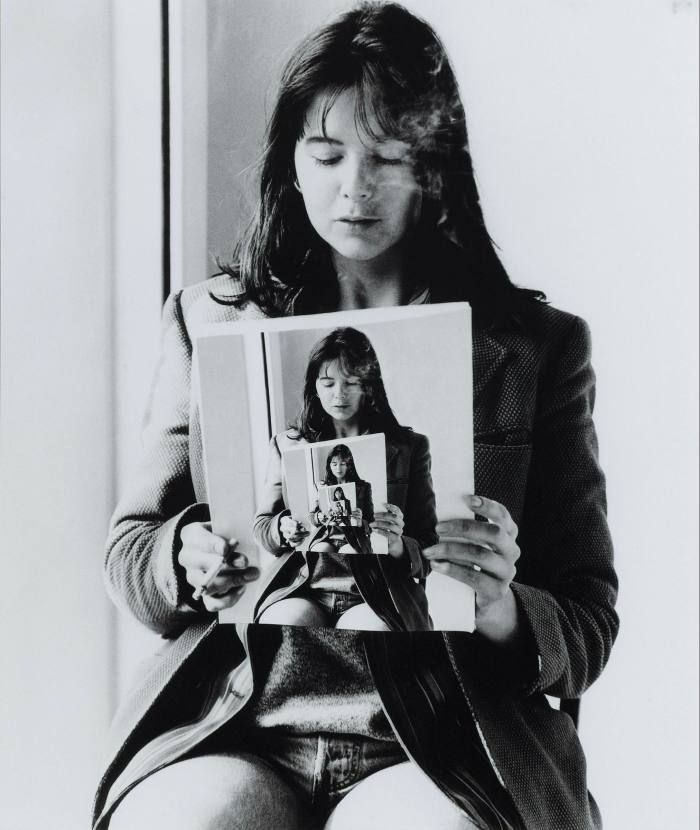

Wearing Masks is so cleverly convoluted that it’s almost as if she had organised her whole career around that punning title. Unlike Arbus, she is less interested in observing others than in having them observe her. She is her own chief obsession, and the question she howls into the existential murk — “Who am I, really?” — is one she tackles with help from an army of collaborators. As both photographer and subject, she slips from costume to costume, from impersonation to impersonation, until the donning and doffing of masks finally becomes a little wearing.

The show ends where it ought to begin, with a 2018 project called “Wearing, Gillian” that sets out the terms of her career. Working with the advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy, she produced a five-minute video about herself. Or maybe it’s about someone purporting to be her.

“Turner Prize-winning artist Gillian Wearing is casting perceptive actors to play her in a short film,” read the online ad she placed. “Male and female talent, aged 22 and older, is wanted to portray Wearing, though the actor does not need to look similar.” The result is a mesmerising and disturbing whirl, in which the faces of more than a dozen non-lookalikes recombine digitally with the artist’s face to form a conglomerate persona. The only constant is a hair-do.

This chorus of avatars makes provocative statements such as “I have only been faithful to one partner” and “I’m adopted and my parents don’t know that I know.” We don’t know either — whether these uncorked secrets belong to the actors or to the character they all play, or if they’re just inventions. Wearing is determined to keep the waters of identity murky. “One of my hopes is that the performers will be able to be a more convincing me than me,” she has said. The piece is an elaborate realisation of a fantasy I suspect many have shared: to send others out into the world in our stead and let them suffer our mortifications.

Wearing also performs the converse trick of passing as a whole array of strangers. In the photo series “Spiritual Family”, she is the star of a one-woman show with the ultimate costume chest. Equipped with custom wigs, silicone prosthetics and creepily lifelike masks (courtesy of artisans from Madame Tussauds), she metamorphoses into artistic heroes: Arbus, Georgia O’Keeffe, Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol.

There’s a chain of references and meta-references at work. Warhol and O’Keeffe were virtuosi at cultivating their own image, and on one occasion they colluded in each other’s mythmaking. Warhol photographed the semi-fossilised O’Keeffe in 1980, then silkscreened the picture on to canvas. Now Wearing invokes them both for her own greater glory.

Warhol was the prophet of displaced exhibitionism. Even before Arbus, he poked at the crack between persona and personality, always hoping it would widen. He trained his movie camera on the faces of his subjects and left it there for long stretches, trusting that they would eventually reveal . . . something. His relentless concentration on surface yielded not depth exactly, but a sense that we are all always looking at each other through a brittle screen.

Arbus was more analytical. She had a talent for sniffing out the significance of setting and stuff, accumulating detail until it illuminated her subjects’ place in the social order. Wearing pays tribute with a statue that the Public Art Fund has temporarily installed near the entrance to Central Park, at Fifth Avenue and 59th Street. A vigilant bronze Arbus hangs out on the plaza in leather jacket and tennis shoes, camera at the ready.

The Guggenheim show sharpens the contrast between idol and idoliser. Wearing slips into Arbus’s face, but the effect is flat and dead. The real eyes we see beneath the synthetic skin reveal nothing. Curators Jennifer Blessing and Nat Trotman insist on Wearing’s profound empathy, but they unsuccessfully attempt to ward off a set of oft-lobbed charges: that she exploits, intrudes and manipulates. She does all three.

Wearing made a splash in 1992 with the project “Signs that say what you want them to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say”. She collared random Londoners on the street and photographed them holding up handwritten cries and confessions. A well-coiffed young businessman with a slight smirk holds up the block-cap scrawl: “I’m desperate.” “HELP,” signals a helmeted bobby. “My grip on life is rather loose,” a beautiful young woman admits. The series is stunning, a composite portrait of a UK in crisis, broadcasting the anguish that lurks beneath polite public blandness.

That success whetted her appetite for more lurid revelation, and she placed ads inviting members of the public to disguise themselves in store-bought costumes and then spill their deepest secrets on camera. These early works proved prescient, and as social media and its culture of self-disclosure took hold she continued to produce confessional extravaganzas. After “Secrets and Lies” (2009) came “Fear and Loathing” (2014), a two-screen video filmed in Los Angeles, complete with high-tech prosthetics and elaborate backgrounds.

No matter whose story she’s telling or whose face she’s got on, what gives Wearing’s work its energy is a core of molten narcissism. Maybe that’s why she’s at her best working with professional actors, who sacrifice their claims to identity and whose thoughts and behaviour she can script.

In the black-and-white video “Sacha and Mum” (1996) a mother and daughter grapple violently; the older woman’s attacks verge on abuse. Yet they also comfort one another. The two whip between love and hate to a soundtrack of muffled grunts and cackles. In another harrowing video, “Bully” (2010), a young man directs a re-enactment of a traumatic scene from his childhood. After watching it unfold, he breaks into a tearful rage, hurling accusations at the actors who play the victim, the tormentors, and the bystanders who let it all happen. It’s here, in this nightmarish terrain between performance and dream, where the haze of memory yields an artwork of unbearable power, that Wearing becomes most fully herself.

To April 4, guggenheim.org

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here