The central Athens apartment of Andreas Angelidakis is in Exarcheia, a district noted for its low tolerance of the status quo. Anarchist slogans and disorderly discussions dictate the vibe here, and its unruliness naturally attracts artists. Angelidakis’s home seems to offer a different kind of Athenian story, however. His armchairs are built with armrests made to look like ancient marble columns; fabrics with classical motifs hang from the ceiling. It is, on first glance, like a soft-furnishing homage to the golden age of Pericles.

But the look is partly temporary, says Angelidakis, who is using the apartment for putting the finishing touches to his new exhibition at Paris’s Espace Niemeyer, running until October 30. The installation, commissioned by watchmaker Audemars Piguet’s contemporary art programme, bears the portentous title “Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity”. But its ironic intent is clear from the first viewing.

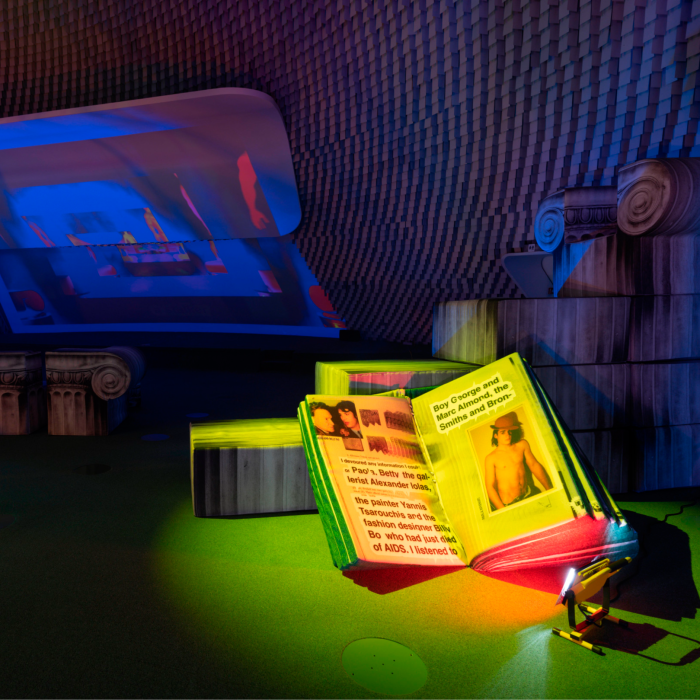

The softness of the fabrics and furniture, built with foam blocks, is a crucial part of the work: here are the famous monuments of Greece’s capital city, rescued from their clichéd and formulaic reproduction by way of their witty deconstruction. In real life, the antiquities of Athens are solemn, imposing reminders of the city’s past glories; in Angelidakis’s warm space, they are welcoming and provide safe refuge from the frenetic outside world.

It is a place where visual puns abound: a series of small statues of a naked man see him, first, standing on the Ionic capital of a column; then the capital seems to rise through him and becomes something like a puffball skirt; then, rising still further, it resembles the protective padding of an American football shirt; and then, finally, it wraps around his eyes like a virtual reality headset.

But there is more to the show than that. The “Center” has a philosophical purpose too; a kind of provocative recasting of ancient history. “I have been obsessed with architecture and antiquities since I was a kid,” Angelidakis tells me. “My initial response [to receiving the commission] was to explore this idea of ‘soft ruins’, setting up this centre which would be a place just to relax and hang out.”

But then he conceived the idea of the centre as “an organisation in search of something”, which would be based on a fusion of literary history, and his own autobiography. His installation is loosely centred on the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the remnants of which still stand proud in the centre of the city, and which became an important space in his upbringing. “It used to be a gay cruising area,” he says, and he is not talking about antiquity here. “I remember clearly the first time my friend took me there, and I saw all this activity going on right next to the temple. It showed me a totally different part of Athens. And I began to find my own version of the city, and how to look at antiquity.”

The more deeply he researched his subject the more interested he became in the marginalia behind the familiar stories. The temple was initially commissioned in the sixth century BC, during the time of the Tyrants who ruled the city, only to be abandoned by the democratic government that succeeded them and disliked the colossal scale of the project.

Centuries later, the Roman emperor Hadrian, as part of a grand building programme, decided to complete the building, the remains of which we see today. But it was not destined to remain intact, and was largely dismantled in the medieval era for its marble. It was among these reversals of fortune and layers of interpretation that Angelidakis found inspiration.

In the earliest photographs taken of the temple in the mid-19th century, for example, there is a tiny hut resting on top of a couple of its columns. It was the abode of a Stylite monk, who reportedly lived there for 20 years. “Of course the archaeologists demolished the hut, and even erased it from some of the photographs,” he says. “It was a story that did not fit their narrative.”

Now a version of the hut is on display in his centre in Paris. “Looking at the past couple of years and the behavioural experiment of Covid, it struck me that we have all become kind of soft Stylite monks, except that it is not the column that is keeping us high, but all the things we used as relief, from antidepressants to vitamins and energy healers.”

Another incidental story from the temple’s modern history concerns the collapse of one of the columns, which broke into fragments. “It was interpreted as a bad omen, there were a lot of superstitions and rumours going round,” says Angelidakis. “So people flocked to see the fallen column.” He points to an antique photograph on the wall, which shows the crowds. “You see those tables all around? They were used to serve coffee to everyone who came to look. And they became the first cafés in the area.”

If his work is challenging traditional narratives of antiquity, I ask him what kind of narrative should be told. “It is not so much giving a new narrative, as asking questions,” he replies. He refers to the demolition in the 19th century of the mosque that used to stand in the centre of the Parthenon. “I would like to know why the Parthenon is considered less interesting [with] a mosque inside it,” he says.

While on the subject of that particular building, I ask if he has any views on the possible return of the Parthenon sculptures. “Honestly, it is not the kind of subject that the Center would approach,” he says playfully, nestling his personal views inside his fictional organisation. “It is a subject which has become oversaturated. I love the Parthenon frieze, but I mostly use Google when I want to see it — I am not going to go to a museum.”

Angelidakis trained as an architect at the Southern California Institute of Architecture, attracted by the school’s conceptual approach to the discipline. He describes his methodology as a reversal of the “representation-to-realisation sequence of the production of buildings”, which essentially means he doesn’t build anything. Does he have plans to? “I don’t think so. When I went to Los Angeles, I figured out why I wanted to be an architect, which was to understand the concepts behind, and reasons for, buildings.”

The housing of his project in the Espace Niemeyer, designed in the 1960s by Oscar Niemeyer as a headquarters for the French Communist party, could not be more fitting, he says.

“Niemeyer was one of those architects who most clearly envisioned public space and public functions. But it was for a kind of future that never materialised. We don’t all work in offices like Brasília, with amazing sofas and brutalist interiors. Whereas I am looking at a past which might have been slightly different from what we imagine, and whose story is still malleable.

“So it is putting a flexible past into a future that is imaginary. That is so perfect.”

Notwithstanding his teases with time travel, Angelidakis has some pointed comments to make about present-day Athens in his installation too. There are, in one corner, some long plastic bins piled upon one another, of the kind that adorn any urban building site. “The Center found these rubble chutes around the place,” he says deadpan. “But I saw them as columns. A kind of new architectural order for the city. The Airbnb Order.”

‘Andreas Angelidakis: Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity’, Espace Niemeyer, Paris, to October 30, espace-niemeyer.fr

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here