They’ve voted their favourite stars into politics, forced filmmakers to rewrite movie endings, rioted with rival fans, died by suicide following the death of a favourite actor. There’s a particular kind of frenzy to fandom in south India.

In Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, there are temples devoted to men such as MG Ramachandran and Rajinikanth. Pilgrim routes take detours to pass their homes. People sell family jewellery to pay for cutouts so large they eclipse theatre buildings.

Even so, when Kannada actor Puneeth Rajkumar died in October, aged 46, and the Karnataka government banned the sale of alcohol for three days, large parts of India were surprised. Was this really necessary?

To those who lived through the days following the death of Puneeth’s father, the legendary superstar Rajkumar, it came as no surprise. The Karnataka state government bungled that occasion badly, as did the police machinery, says Kannada film historian N Manu Chakravarthy.

Rajkumar was Karnataka’s sweetheart and first superstar. Having starred in over 200 films from the 1950s to 2000, this was a man who was beloved for representing all classes and castes, as well as representing Kannada values and virtues, on screen and off.

On the day he died in April 2006, aged 76, thousands descended upon his home in Bengaluru and gathered outside the Kanteerava stadium, where news had spread that his body would be laid out in state. No arrangements were made to channel this grief.

Hours passed before the body arrived. When it did, the crush was so great that there was a near-stampede. Rioting broke out. Vehicles were set on fire, theatres were vandalised. At least eight people died.

“So when it came to Puneeth, who was beloved too, the state woke up,” says Chakravarthy. They banned alcohol from being sold in the state, heightened security, and moved the body to the Kanteerava stadium two hours before the announced time. The day ended in grief but not chaos.

***

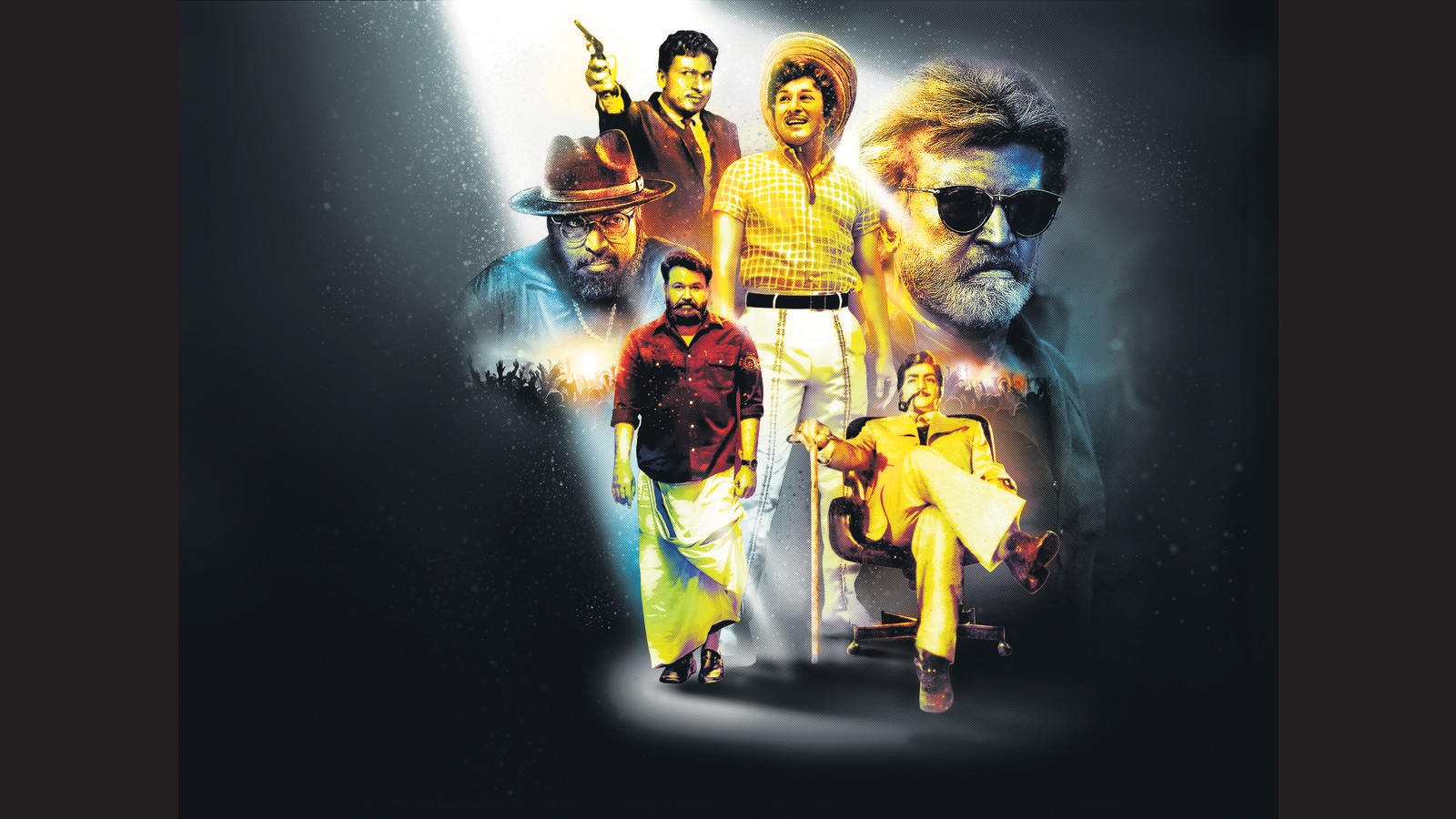

Across the four industries — Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and Kannada — the stars loom larger than in any other film industries in the world.

In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, fanclubs have helped drive political careers. Superstars from Tamil Nadu’s MGR (MG Ramachandran) and Jayalalithaa to Andhra Pradesh’s NTR (NT Rama Rao) have risen to be chief ministers of their states.

In Kerala, the craze over Mammootty and Mohanlal compelled filmmakers to film two different endings for the 1998 Malayalam film Harikrishnans, so that each of the two men would get the girl, depending on where you watched it.

As it is around the world, the era of this kind of superstardom is ending, except perhaps in Tamil Nadu, where a new generation of superstars seem to have emerged. The audience itself has become more fractured, as speakers of other languages engage with cinema from the south via streaming platforms, outside the theatre system.

So the mega blockbusters that emerge from the south are no longer linked to the same small set of names. The Telugu Baahubali movies (2015 and 2017) are now India’s most successful franchise ever, raking in over ₹2,000 crore in all box offices around the world. Its stars, Prabhas, 42, and Rana Daggubati, 36, have shot to national fame. But you don’t see the same kind of hysterics around these men. The closest you get to it is in Tamil Nadu, where Tamil cinema’s Vijay has seen each of his last two films, Bigil (2019) and Master (2021), bring in over ₹300 crore, and where he is perhaps as big as Rajinikant was in his prime (and still is).

“The making of a superstar is tied to the theatre space, where the gathering takes place and people are on their feet. The shift to digital, personal and domestic modes of viewing is not amenable to superstardom. And neither are the subtler narratives,” says film critic CS Venkiteswaran. “Superstardom can only exist within a certain cinematic tradition.”

And so many of the megastars of south Indian cinema today are the megastars of yesteryear: Rajinikanth, 70; Chiranjeevi, 66; Mammooty, 70; Mohanlal, 61. These much-larger-than-life icons don’t often appear in new films, but, in at least three of the four states south of the Vindhyas, no new names have taken their place.

As their age draws to a close, take a look at the world of the south Indian cinema fan, as they knew it, and as it is now.

.

Kannada: Superstars and superfans

When Kannada actor Rajkumar died in April 2006, Bengaluru came to a halt. Shops shut. Traffic thinned. People cleared out of the streets. It was an undeclared bandh. Kannada cinema had just lost its biggest star and the people were heartbroken. They also knew what was coming.

By evening, buses were being smashed. A police car was set on fire. Thousands gathered outside the late superstar’s home in Bengaluru. At the city’s Kanteerava stadium, where his body arrived hours later than announced, crazed fans caused a near-stampede. Those who couldn’t catch a last glimpse of him as his hearse left for his last rites began pelting stones at the vehicle in frustration, as his son Shivrajkumar sat inside.

Eventually, the police had to quell the crowds with their lathis, and tear-gas.

Rajkumar (given name Singanalluru Muthuraj) reigned for five decades and acted in over 200 films. His early roles are a crucial study in what endeared him to the public. Historical, mythological and social films were the staple of the time, and Rajkumar represented just about every demographic.

He played a Bedara tribal in Bedara Kannappa (1954; often called the first Kannada superhit because it ran for 100 days and won a National Award). He played the Sufi poet Kabir in Mahathma Kabir (1962); an upper-caste sage in Mantralaya Mahatme (1966); the epic demon of Hindu scripture Hiranyakashipu in Bhakta Prahlada (1967); a potter in Bhakta Kumbara (1974).

“It’s why Rajkumar became so important,” says Kannada film historian N Manu Chakravarthy. “Because he upheld the Kannada values and culture of inclusivity. He emerged out of Kannada consciousness and represented Kannada culture.”

Rajkumar’s successors tell a telling tale too. By the mid-1970s, there was Vishnuvardhan (1950 – 2009). “It was his role as an angry young man in Naagarahaavu that catapulted him to fame,” says Chakravarthy.

Vishnuvardhan didn’t play good guys. In Naagarahaavu (Cobra; 1972) he is an ill-tempered teacher courting two women. In Gandhada Gudi (Temple of Sandalwood; 1973), he plays the villain to Rajkumar’s forest-officer hero.

But the audience was changing. Cinema halls were mushrooming across the state and tickets were getting cheaper. The working-class and the youth were showing up in large numbers. And they related to the anger and frustration of the men Vishnuvardhan played. “Sort of like what Amitabh Bachchan was doing on the national stage,” says Chakravarthy.

Vishnuvardhan was in his mid-20s, Rajkumar in his 50s. “It created a kind of counter figure,” Chakravarthy says. “The youth found a voice in this younger, more rebellious figure. Which is when the first abhimanagala sanghas or fan associations were formed.”

The fan associations, comprising largely young men, were concentrated in Bengaluru and Mysuru. They became notorious for their “passion”.

“The Rajkumar fans though were very powerful,” Chakravarthy says. He recalls watching a young man in Mysuru in the ’80s whose cycle was full of images and titles of his demigod Vishnuvardhan. “Rajkumar fans got him off it and smashed the cycle,” he says.

The drama reached fever pitch when, rather incredibly, Rajkumar was abducted by the dacoit Veerappan in 2000, and held for ransom. As the police and state government rushed into action, schools were declared closed and remained closed for two weeks, alcohol was banned, the film and television industries came to a halt. There are no clear records of exactly how, but his release was secured 108 days later.

The cult of the superstar lingers on in Karnataka, but there hasn’t been another Rajkumar or Vishnuvardhan. The new generation of stars such as Darshan, Yash and Duniya Vijay are still macho men, always romancing beautiful women on screen, defeating entire armies with their bare fists (or a machete), but they are not demi-gods.

If anyone came close to being one it was Rajkumar’s son Puneeth Rajkumar. He was loved also for building and maintaining schools and his other works of philanthropy. When he died last month, aged 46, messages began to do the rounds on WhatsApp advising people to stay home. The Karnataka government issued a three-day ban on the sale of alcohol. People were heartbroken, of course. But the preparations were made in a timely manner; his body arrived at Kanteerava stadium two hours before the announced time. Fans bid tearful farewells, shops remained open and the city returned to its day.

Malayalam: Two sides to the ideal man

In 1998, the Malayalam film Harikrishnans, starring Kerala’s darlings Mohanlal and Mammootty, was released. The story, about two high-profile lawyers who get involved in a murder case, was the highest-grossing film of that year.

But here’s what’s interesting about it: In some parts of Kerala, where Mohanlal fans dominated, Mohanlal got the girl (Juhi Chawla) at the end of the film. In other parts, where Mammootty fans ruled, a different ending was screened, and Mammootty got the girl.

Director Fazil released two versions. (Though the censor board soon halted screenings of the second; it had never been submitted for clearance. And any Harikrishnans print you see now will end with Mohanlal getting the girl.)

The extreme Mammootty-Mohanlal fan rivalry has endured for about five decades, though the actors have always been friends. Both men — Mammootty is 70 and Mohanlal is now 61 — are still kings of mainstream Malayalam cinema. They’ve acted in hundreds of films, played gods and gravity-defying heroes, family men and villains.

Trying to figure out who is better loved would be a futile task. And yet, each of the two men represents something starkly different.

“There is a kind of ambivalence to the type of masculinity Malayalee society prefers,” says film critic CS Venkiteswaran. “An ambivalence between a caring, vulnerable sort of man who is flawed, and a dominant, masculine, tragic hero who takes charge. We call them the Rama and Krishna of cinema.”

It’s an epic duality that has played out in the cinematic world for generations. Before Mammootty-Mohanlal, there were (on a far smaller scale) Prem Nazir and Sathyan, in the’60s and ’70s. “Today, there is an attachment to Fahadh Faasil and to Prithviraj Sukumaran, and it is the same kind of ambivalence at work.” Faasil is the doe-eyed, soft-spoken indie darling leading the new wave of films coming out of Kerala. Sukumaran is the stoic mainstream action hero.

But in Kerala, the superstar era ends with Mammootty-Mohanlal. It is unlikely that there will ever again be the kind of craze those men enjoy. The kind of craze that reportedly caused one female fan, for instance, to schedule a C-section so that her child could have the same birthday as Mohanlal (May 21, for anyone who’s wondering).

“The kind of narratives the new generation of filmmakers are making are not what brings stardom,” says Venkiteswaran. “They are not dealing with all-powerful masculine figures, which doesn’t allow for such superstar figures to be born. Add to that the shift to digital and personal domestic mode of viewing, which is actually not very amenable to superstardom.”

What the new stars do have is greater national appeal. Few fans of cinema don’t know or haven’t watched the works of Faasil (Joji, Kumbalangi Nights), Lijo Jose Pellissery (Jallikattu), Jeo Baby (The Great Indian Kitchen).

But two endings instead of one? More like a different ending overall. “The superstars know their era is over,” Venkiteswaran says.

.

Telugu: Of emperors, demigods and Baahubali

The Telugu film industry is one of the largest in India. In 2015, it set a new record for that heft when Baahubali: The Beginning became India’s highest-grossing film ever. The film has so far raked in over ₹600 crore. Baahubali 2 (2017) brought in thrice as much. The film was dubbed in over ten languages and released around the world. Its stars, Prabhas, 42, and Rana Daggubati, 36, shot to national fame.

But they don’t prompt the kind of mayhem that the Telugu fan of the yesteryear Telugu superstar routinely caused. For one thing, they don’t have the grandiose titles.

Before he was chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, for instance, NT Rama Rao had an even rarer title: Viswa Vikhyatha Nata Sarwabhouma (World-Famous Emperor of Drama). And that wasn’t the most of it.

In a career that started in the ’50s and stretched over 300 movies, NTR played a series of mythological Hindu deities and kings. He shot to fame with the epic Mayabazar (1957), in which he played Krishna. He would play the deity another eight times in his career. Even that wasn’t the most of it.

After Sri Venkateswara Mahathyam (1960), in which he played the deity Vishnu, pilgrims began stopping outside his house in Chennai for “darshan” on their way the Venkateswara Vishnu temple in Tirupati.

Andhra’s first fan clubs were NTR fan clubs, says SV Srinivas, Telugu film scholar and author of Politics and Performance: A Social History of Telugu Cinema. “By the ’70s and early ’80s every major star of the time, from NTR and Akkineni Nageswara Rao to Krishna and Chiranjeevi, had fan clubs.”

In the beginning they were largely unorganised, informal groups. Then they started competing with each other to see who could celebrate new releases the loudest, create the biggest cutouts, generate the most hysteria on opening day (people in delirium; aartis and coconuts; milk poured on posters). This competition occurred even between fan clubs dedicated to the same actor.

“A lot of the time, these clubs were loosely organised by caste, not by design, but because that’s how the groups would organically form,” says Srinivas. “And so there were instances of Dalit fans in one club, and Reddy fans in another club, both Chiranjeevi fan clubs, and from the same area, but they considered themselves rivals.”

Telugu fans are so unusually film-crazy that theatres in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana still have what are called “benefit shows” for the biggest releases of the year.

“These are shows that are screened before the first day, first show, so sometime around 2 or 3 am,” says Srinivas. “It’s a form of fundraising for the clubs. Each fan club gets a certain number of tickets, and theatre management lets them to sell these tickets at whatever rate they want. Some sell for more than ten times their original value.”

Other elements of the fanbase’s power remain. Filmmakers have, for instance, rewritten endings to appease angry fans. Fans were so unhappy when the character played by Mahesh Babu, then a young star of 26 but also son of the revered actor Krishna, died at the end of Bobby (2002) that the film was withdrawn and re-released with a happier ending.

“There are stories of directors going underground because fans didn’t like a film,” laughs Srinivas. “And while all this happens, if a film doesn’t do well, everyone is blamed except the star. Sometimes it’s the fault of the heroine, or the director brought bad luck. But if an actor has received superstar status, then he can do no wrong.”

.

Tamil: Stars. CMs. Rajinikanth

Before the phenomenon of Rajinikanth, there was MG Ramachandran or MGR, the filmstar with arguably India’s most frenzied fan following. A reported 31 fans died by suicide the day he died in December 1987, aged 70; another 40 to 100 cases of self-immolation were reported.

More than a million lined the streets as his funeral procession made its way from his home in Chennai to the city’s Rajaji Hall, where it remained in state for two days as thousands from across Tamil Nadu travelled to pay their respects.

MGR was Tamil cinema’s first megastar. It was his lead role as a king’s righteous general in the historical drama Manthiri Kumari (1950) that made him a star. He played a series of good guys over the next 20 years, and was seen by audiences as embodying all the good qualities he portrayed on screen.

Which probably explains his easy segue into politics — MGR had been CM for 10 years at the time of his death. The transition to politics has since been attempted by fellow Tamil superstars Rajinikanth (now 70) and Kamal Haasan (67) without much success, but was replicated by one of his leading ladies, Jayalalithaa (1948 – 2016), who served as chief minister of Tamil Nadu for more than 14 years.

MGR set the template for superstardom in his state. Tamil cinema was deeply rooted in the politics of the Dravidian movement, says film historian N Manu Chakravarthy. “MGR was a product of the DMK vision of social justice. The foil to his benevolent hero persona was Sivaji Ganesan, who was not very political but was popular.”

When Rajinikath stormed the screens in the 1980s and ’90s (he’d been acting since the 1970s but this is when he became a superstar), he brought something Tamil cinema had never seen before — the cigarette flip, the flicking of the sunglasses, the strut. “His style was different,” says film historian Theodore Baskaran.

He had starred in several remakes of Amitabh Bachchan films: Shankar Salim Simon (1978) was a remake of Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), Naan Vazhavaippen (1979) was a remake of Majboor (1974), Billa (1980) was a remake of Don (1978).

Double roles and triple roles followed, along with Hindi films alongside Amitabh Bachchan and later Aamir Khan. His fans took fandom to strange new peaks: there were stories of men taking loans on family homes and gold to pay for giant cutouts of him to mark new releases.

“The fan clubs and their activities are on the decline,” says Baskaran. But they’re not gone. The new generation of Tamil superstars such as Ajith, 50, Dhanush, 38, Vijay, 47, and Suriya, 46, also enjoy massive followings and loyalists whose lives revolve around their lives, successes and release dates. There are crossovers into politics too.

Recently, a village panchayat election was won by a group that contested as All India Thalapathy Vijay Makkal Iyakkam or the All India Captain Vijay People’s Organisation.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here