Heroes Behaving Badly: The Wondrous and Bastardly Creations of Jack Vance

by Brian Murphy

Cugel the Clever probably isn’t a guy you want to invite to dinner.

You’d be guaranteed belly laughs and an unforgettable night’s entertainment … until later, when the check comes due. And you discover he made off with the priceless silverware set you inherited from your grandmother, and tried to make time with your wife.

Bastard!

Cugel is a loveable rogue, nicknamed “the Clever” for good reason; he consistently escapes harrowing scrapes and near-death through pluck and quick-thinking, which makes him and his adventures entertaining for the reader, even when he’s behaving badly. Which is quite often.

That Jack Vance can make us love a not-so-nice hero speaks to his skill as a writer and the incredible thematic and stylistic flexibility of the sword-and-sorcery subgenre. Some critics claim that sword-and-sorcery heroes must contain some degree of virtue, if not be outright virtuous, else we would not enjoy their stories. Cugel is certainly not without any virtue, though sometimes you have to squint to see it. But it doesn’t matter all that much; his roguish charm has a virtue all its own. Sword-and-sorcery has its rogues, and we love them, too.

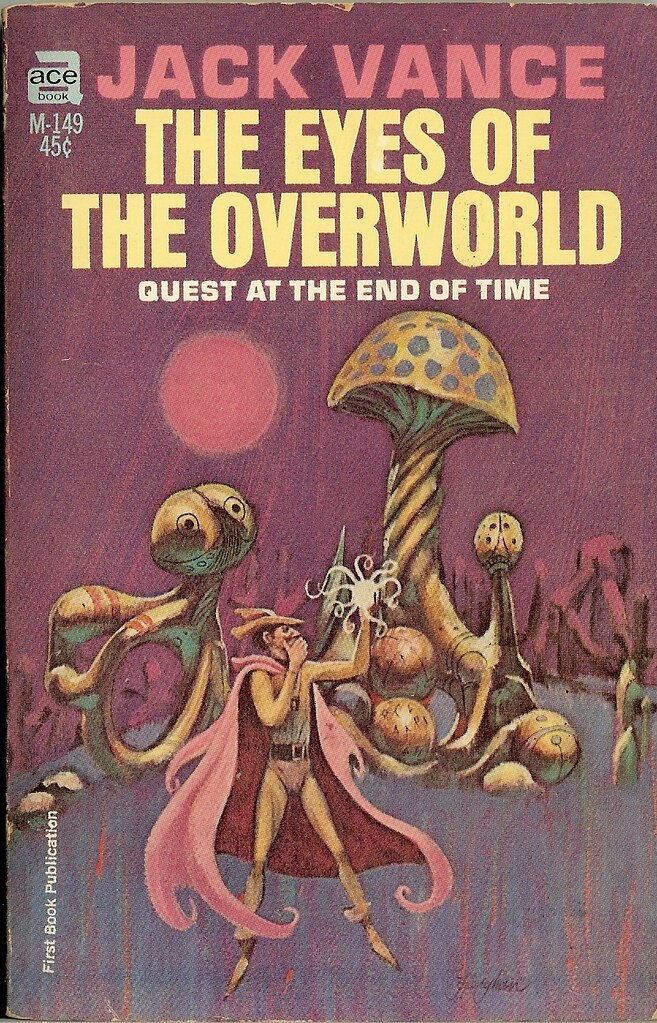

Cugel’s stories (initially published as short pieces in the likes of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Flashing Swords!, later collected in The Eyes of the Overworld (1966) and Cugel’s Saga (1983) are part of a series of interconnected stories set in The Dying Earth universe. It’s our own earth, albeit one in the far-flung future when the sun is going dark. So while it is peopled with monsters and magic, it also concerns humans behaving badly, as we are sometimes wont to do.

Cugel’s “saga” begins in the least lofty manner imaginable. Caught in the act of robbing the home of the sorcerer Iucounu, Cugel is forced to embark on a quest to recover an artifact, a violet hemispheric gem once possessed by a demon. It is later revealed to be one of a pair of “eyes”; Iucounu has the other. Iucounu whisks Cugel away to the land of Cutz and embeds the creature Firx onto his liver to ensure he will complete the quest. Should Cugel’s resolve waver (and it does—coin and women are a siren’s song), Firx steers him back on course with sharp barbs in his inner anatomy.

A series of daring and amusing scrapes and adventures unfold. Aside from a few bouts of melancholy, the stories are largely comic and strange as Cugel is forced to flee uncomfortable and awkward situations of his own making. Moments of laugh-out-loud humor stud the stories. Cugel accidently eats a small, jellylike creature that has taken 500 years to summon; he “humbly” proclaims to the resident of a palace of which he has begged entrance: “My name is of no consequence. You may address me as ‘Exalted.’”

So, we have Cugel, the awful but also the charming, and clever. But Vance also offers up some darker protagonists, with no redeeming qualities. In “Liane the Wayfarer” we meet one. Liane casually kills a merchant and is put out that the man dared to splash blood on his sandals. The nerve! He plans to force himself on a golden haired “witch” after spying on her as she bathes in a stream; she barely manages to fend off his amorous advances with the threat of ensorcelled knives. He casually kills an old man by dropping a rock on his head. Yet “Liane the Wayfarer” is a must-read because of the world Vance creates, and the monster (Chun the Unavoidable) that awaits this “hero” to deliver a terrible comeuppance.

While we see echoes of Cugel as far back as Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Vance’s direct precursor is James Branch Cabell, whose Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice (1919) helped establish the roguish hero template. The book is a series of picaresque adventures Jurgen undertakes for self-gain, glutting himself on pleasures of the flesh. Its unrelenting cynicism, irony, and humor are hallmarks not just of Vance but the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tales and Moorcock’s Elric series. In Jurgen too is the outsider. “But for all his laughter, he could not understand his fellows, nor could he love them, nor could he detect anything in aught they said or did save their exceeding folly.” Jurgen was judged so risqué that the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice brought charges of obscenity against the novel and attempted to have it banned, a move which only fueled the novel’s popularity and Cabell’s career.

Vance was also influenced by Clark Ashton Smith, a piece of scholarship from the pen of Don Herron recently highlighted on the Grognardia blog. Smith of course penned many mercenary protagonists, in sword-and-sorcery circles most notably the thief Satampra Zeiros. We can see in Vance echoes of Smith’s style but also the same anti-heroic strain.

While perhaps not as well-known in sword-and-sorcery circles as the likes of Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, and Michael Moorcock, today Vance has many fans and literary inheritors. Michael Shea published a Vance-authorized sequel to the Cugel stories with A Quest for Simbilis (1974), which picks up from the end of Cugel’s Saga. Shea went on to write his own original fiction, most notably Nifft the Lean (1982), which won a World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. Its protagonist owes much to Vance and his creations.

More recently, author Schuyler Hernstrom channels Vance’s style and sensibility in the likes of Thune’s Vision and The Eye of Sounnu, which include a wide range of stories but perhaps most notably a pair of roguish heroes. “Mortu and Kyrus in the White City,” recalls Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser with its hulking Northern barbarian Mortu and impish companion Kyrus (the latter is a philosopher trapped in a monkey’s body, Mortu a motorcycle riding warrior of the wastelands). But the style is that of Vance, as are Hernstrom’s stories “The Star-God’s Grave” and “The Tragedy of Thurn.” I also detect something of Vance in the works of Joe Abercrombie, though possibly second-hand, through the likes of George R.R. Martin.

Vance influenced gaming, and not just in his wildly inventive magic system. We knew how a chaotic good-aligned character should operate because of Cugel, and chaotic evil because of Liane. Many Cugel-like characters populate gaming tables today.

But Vance’s greatest legacy are his stories of richness and variety and wild imagination, delivered with an inimitable prose style that has its own adjective–Vancian. Wonderful writing, humor, wondrous visions … but also human frailty, weakness, and “heroes” behaving badly. Even in the irredeemable Liane, Vance proves that we can enjoy stories of scoundrels and rogues, if the story is well-told and the craft of a sufficiently high degree.

And when we read Vance we are in the hands of a master storyteller, unafraid to laugh at the dark.

Brian Murphy is the author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Learn more about his life and work on his website, The Silver Key.

Header image is from the Hungarian edition of Eyes of the Overworld.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Gaming News Click Here