While some may welcome legislation that increases housing stock and density — in an effort to bring down rent and real estate prices — many people are unhappy with the move, saying it’s reminiscent of other legislative oversteps that have gone down in Denver in the past.

“It’s the biggest power grab from a governor since the great City Hall War of 1894,” says Rich Grant, former longtime communications director for the city’s tourism organization, Visit Denver. Grant points to the historical event as a great lesson in the consequences of state overreach.

SB23-213 was introduced in late March by Senator Dominick Moreno, Representative Iman Jodeh, and Representative Steven Woodrow. The bill intends to establish “a process to diagnose and address housing needs across the state, [address] requirements for the regulation of accessory dwelling units, middle housing, transit-oriented areas, key corridors, and manufactured and modular homes.”

It also would prohibit “certain planned unit development resolutions” and “local government from enforcing certain occupancy limits.”

Essentially, the proposed legislation would override local rules that block dense forms of development such as duplexes and triplexes in Colorado’s urban areas. Critics mainly cite the override of local authority as their issue with the bill.

“As the Chair of Denver’s Land Use, Transportation & Infrastructure Committee I am beyond disappointed that me and my colleagues have not been part of the process nor invited to be part of the stakeholder process,” tweeted Denver City Councilwoman Amanda Sandoval on April 6, referring to the bill’s creation.

“As a Councilwoman who was born and raised in the Northside where I have the honor of representing my community as their Councilwoman we have directly seen the impact of displacement and gentrification,” Sandoval said.

In an op-ed posted to coloradosprings.gov, the mayor of Colorado’s second largest city, John Suthers, called the bill “a breathtaking usurpation of control of local land use by the State,” adding that the bill “would impose top-down State land use standards that would essentially deprive local citizens of any meaningful input into the land use practices that directly impact their quality of life.”

Says Grant: “I spent my entire life telling people to come to Denver and then go home!”

To him, local zoning laws were put in place for a reason: to protect the history and character of local neighborhoods. But Grant takes issue with the state’s legislative overstep on principle, which is where the City Hall War of 1894 comes in and provides great context, he says.

What was the City Hall War of 1894? Well, first you need to know who Soapy Smith is.

Way back in the day, Colorado’s towns had a serious law-and-order issue. In 1893, “Corruption, graft, and bribery were at their worst” and “crime was rampant,” according to the book The Reign of Soapy Smith, Monarch of Misrule in the Last Days of the Old West and the Klondike Gold Rush, by William Ross Collier and Edwin Victor Westrate.

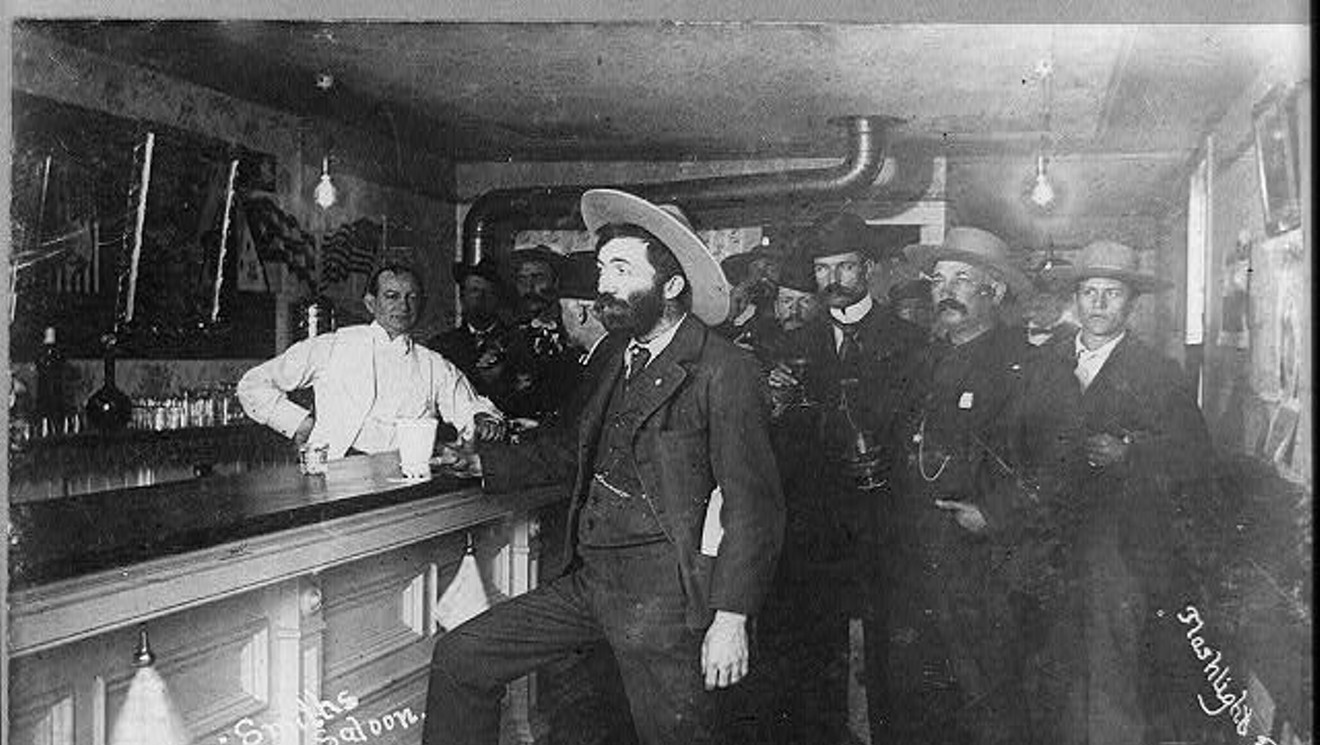

Jefferson “Soapy” Smith — one of the most prominent con men of the 1800s, according to Legends of America — ran a large-scale organized gambling ring in Denver after moving to the Mile High City with his gang in 1879.

Soapy had swaths of police officers and city officials on his payroll, and that kind of corruption was something that 1893 gubernatorial candidate Davis Waite was determined to take down, according to Collier and Westrate.

The state population was apparently tired of the crime and corruption, too, as Waite won his election easily.

In 1894, he immediately got to work taking down the dirty cops and politicians in the state’s capital city. “The fact that the condition was one of municipal and not state authority did not deter him for a moment,” note Collier and Westrate.

According to the authors, Governor Waite ordered the police and fire commission to “clean house” — as in fire their staff and build back from the ground up. They all refused on the basis that his authority did not apply to them. The governor then called for them to resign, which they also refused to do. Waite declared that if the cops and fire commissioner continued to disobey his orders, he would call out the state militia and show them who was boss “once and for all.”

Not surprisingly, they did not obey Waite’s orders. So the governor called on his militia to advance on City Hall the next morning, write Collier and Westrate.

With word of the impending attack, Waite’s enemies went to the man writing their paychecks: Soapy.

Appointed as head of the city’s defense, Soapy gathered an army of his own, which Collier and Westrate describe as a “desperate crew of dry-land pirates.” The group raided every hardware store and pawnshop for every weapon imaginable. In the morning, Soapy positioned his men in the second-story windows of all the local buildings overlooking an approach to City Hall, as well as at City Hall itself.

The group was able to get their hands on 500 pounds of dynamite, which was brought in on an “express wagon,” say Collier and Westrate. Soapy had former miners in the windows, too, ready to hurl dynamite on any incoming attackers. The police and fire departments also stationed themselves at City Hall with Soapy’s men.

Governor Waite was not deterred upon hearing of the city’s corrupt defenses.

He ordered his militia onward, while the City Hall defenders positioned themselves and waited for the governor’s army to fire the first shot.

The man in charge of the governor’s army, General Brooks, eventually became aware of the true extent of the city’s defenses and called for a negotiation with the fire and police commissioners. The commissioners refused to surrender, and Brooks sent a message to the governor: “If a single shot is fired, they will kill me instantly, and they will kill you in 15 minutes. But if you say fire, we’ll fire.”

Brooks refused to initiate the battle without a personal order from Governor Waite, according to Collier and Westrate.

Their book outlines how Governor Waite “appeared fully prepared to demolish the City Hall in order to prove his authority.” However, he was dismayed by the extent of the prospective bloodshed and threat to his safety.

As the governor’s militia waited for a response, civilians cleared out of town, and one General McCook of the United States Army mounted infantry to come in and end the bloodshed, should it begin.

The governor ultimately dragged his feet on sending a response, and the city sat in quiet tension.

Prominent Denver citizens went to the home of the governor — who was too angry to call off the attack but still too hesitant to give the order to proceed. After a long effort, the citizens calmed him down and the attack was called off, bringing order back to the city.

Governor Waite eventually found a peaceful method of achieving his goal: ousting the crooked commissioners via court order and successfully cleaning out the police department.

Unfortunately, the new police chief and head of the detective force were ineffective at getting a handle on Denver’s organized crime, allowing Soapy and his buddies to continue on with their enterprises. Governor Waite later lost his bid for reelection.

“Polis must think that Hancock and the whole Denver City Council — and mountain towns — are so corrupt with zoning bribes that he has to take matters into his own hands and seize control, because the city will never solve the housing problem on its own,” says Grant.

Grant doesn’t think the local response to Polis’s bill will be quite as extreme as the City Hall War of 1894, nor should it be — although “Colorado Springs definitely has a militia that they could call on,” he jokes.

“It’s funny,” Grant says. “The last time there was this serious an overreach by the state, it ended in, almost, a shooting war and cannons pointed at the City Hall.”

Conor Cahill, press secretary for Governor Polis, tells Westword that the comparison almost makes it seem like Grant “is supportive of the bill.” Says Cahill: “We’re not history buffs like this individual, but this bill is about enhancing property rights and cutting red tape. The overwhelming support for making housing less costly in Colorado comes from the people of the state. The broad coalition to fix our housing crisis is composed of business leaders, organized labor, environmental advocates and housing affordability advocates.

“We need to get this right, because Coloradans expect their elected leaders to do what’s right for Colorado and solve the very real housing challenges they continue to face on a daily basis across our state,” Cahill concludes.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest For Top Stories News Click Here