There’s a video on YouTube, shot at the Placa de Sant Roc in the small town of Sabadell in Spain. It opens with shots of the square, then moves to a man in formal evening wear and white tie, playing a double bass. A little girl comes up and drops a coin into the hat in front of him. A woman with a cello joins him, as a familiar tune takes shape. Soon, there’s a whole orchestra playing, as the delighted crowd takes in a full-blown classical performance. And when the choral section hits, it seems that everyone in that square in Sabadell is singing along, singing a Catalan version of Friedrich Schiller’s most famous words.

The piece, of course, is the Ode to Joy, the choral finale of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony.

Completed in 1824, the 9th Symphony premiered on May 7 that year. The story is well-known. Beethoven had initially wanted it to premiere in Berlin, but when the people of Vienna (where he lived; and which was then also part of Germany) signed a petition begging him to hold the premiere in their city, he relented.

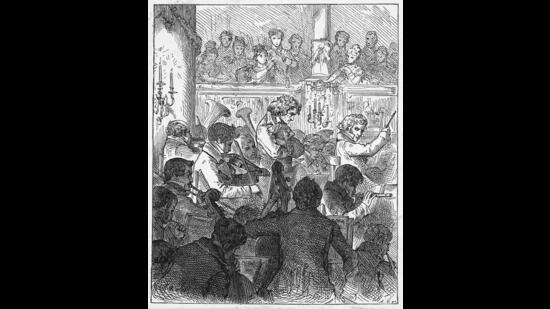

He attended the premiere, his first in 12 years, and everyone who was anyone in Vienna was present. The performance was greeted with rapturous applause, and the deaf composer, who was also conducting the orchestra along with Michael Umlauf, had to be turned around to see cheering audience, which gave him five standing ovations.

The 9th was Beethoven’s first new symphony in a decade (and would be his last full one). It required his largest orchestra yet and had the unusual addition of vocals. No one had heard anything quite like it.

Since that day, it has been not just integral to European culture, but one of the cultural treasures of the world. In 1972, the Council of Europe adopted Ode to Joy as its anthem. In 1985, the European Union followed suit. In 2001, Unesco announced its addition to the world’s cultural heritage list, the first musical work to be so honoured.

For most people, the 9th is interchangeable with the fourth movement of the symphony, the choral section where Beethoven’s music sets the words of German poet Friedrich Schiller on fire in one of the most powerful appeals to a universal brotherhood of humanity.

(The famous first verse “Freude, Schöner Götterfunken…” roughly translates to: Joy! A spark of fire from heaven, Daughter of Elysium, drunk with fire, we dare to enter, Holy One, inside your sanctuary. Your magic power binds together, what we by custom wrench apart, all men will be brothers, where you rest your gentle wings).

It’s also about victory. It’s the music that plays when Alan Rickman’s Hans Gruber watches his plan come to its fruition, as he stands bathed in the blue light of the open vault at the Nakatomi Plaza in Die Hard (1988). It plays as Robin Williams’s charismatic teacher, John Keating, is carried off in triumph by the students of Welton Academy after a football win, in Dead Poets Society (1989).

Its message of brotherhood, hope and victory was on the minds of the Chinese students in Tiananmen Square in June 1989, when they played it on loudspeakers to drown out the messages of the Chinese military. Feng Congde, one of the student leaders, remembers putting the cassette into the system and pressing play. “There was a real transformation,” he says, in a 2013 documentary called Following the Ninth. “It gave us a sense of hope, (of) solidarity, that all people would become brothers”. But even the 9th wasn’t powerful enough to sway the Chinese authorities. “It gave us a moment of hope, but the tanks and the machine guns killed that hope,” says Congde, who was not among those killed, but was the target of a months-long nationwide manhunt and eventually fled to Hong Kong.

The message of hope and victory was on the minds of Chilean protesters demonstrating against Augusto Pinochet’s coup in 1973, as they sang the Spanish version, Himno a la Alegria. It was the soundtrack to the end of the Berlin Wall, as Leonard Bernstein conducted Ode to Joy there on Christmas Day 1989, about six weeks after the fall of the Wall, with the word “Joy” replaced by “Freedom”.

In Japan, where Beethoven’s 9th is called the Daiku (Great 9), performances of it are a year-end tradition, with choruses that run into the thousands.

The 70-minute symphony even determined the diameter of the compact disc in the late 1970s, although whether the decision that it should fit on a single CD was made by Sony co-founder Akio Morita or president Norio Ohga is still undetermined.

The 9th isn’t the preserve of the just alone. It was one of Adolf Hitler’s favourite pieces of music. You can even find a few minutes of Wilhelm Furtwangler’s legendary version with the Berlin Philharmonic in old recordings of Hitler’s 53rd birthday celebrations in 1942. Abimael Guzmán, the founder of the Peruvian terrorist group The Shining Path, was also a fan. The racist state of Rhodesia used Beethoven’s music for its national anthem.

But all that doesn’t change the fact that the 9th Symphony is one of the most powerful pieces of music ever written and written by a man who could only imagine what it would sound like. As Benjamin Zander, the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic, put it in a podcast, “The ninth seems to express, most completely, what human beings are struggling for. It is a battle cry for humanity. It is the hymn of possibility.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here