This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

After a turbo-charged, months-long marketing campaign, Barbie was finally released in theaters this week. In between dance routines and jokes, the movie invites us to ask questions about feminism and the lines between commerce and art.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

All the Sides of Barbie

Over the years, Barbie has been many things: a symbol of unattainable beauty standards, a career woman, an embodiment of the male gaze, an inspiration for young girls. This summer, Barbie is the place to be. My afternoon screening of the movie in Brooklyn yesterday was sold out, packed with delighted people wearing pink. To understand what’s driving the movie’s ubiquity this summer, and to discuss how the film handles feminist themes, I called Shirley Li, a culture writer at The Atlantic.

The following contains light spoilers for Barbie.

Lora Kelley: I’ve seen Barbie everywhere this summer—on billboards, at a pop-up in Manhattan, blanketing my Google search-result pages in pink. Is this kind of marketing campaign normal for a summer blockbuster? Or is there something special about this project?

Shirley Li: The movie is a big swing for Mattel. I think they’ve poured everything they can into its marketing campaign. Mattel has been struggling with the Barbie brand for several years and was looking for a way to turn around Barbie’s cultural relevance. And Barbie happens to be very fun to market.

At the same time, this kind of marketing push, at least for big summer tentpoles, was par for the course before the pandemic. The Hollywood strikes are a factor here as well: The Barbie cast packed in as much promotion as they could on the press tour before the SAG-AFTRA strike began last week.

Lora: Is Barbie a piece of brand marketing for Mattel, or is it a work of art by Greta Gerwig?

Shirley: It’s kind of brand marketing for Mattel—and it’s also a work of art from the writer-director Greta Gerwig. That’s one of the reasons the film is interesting to me. It’s very self-aware of the fact that it’s a movie about a product. But it argues for Barbie as not just a product, but a protagonist—someone who deserves her own heroine’s journey, and whose function is to represent a brand but also represent the ideal of womanhood to young girls. All of that gets wrapped up into this film.

The film invites you to consider all the sides of Barbie. You can’t talk about yourself without talking about the things that influenced you, and often, those are things that you have consumed or bought. We often think the things that make us us are the things we play with, consume, watch, and listen to. We can become very possessive of those things. At the same time, we’re not completely composed of them.

Lora: I’m curious about your thoughts on whether and to what extent this is a feminist film.

Shirley: One of the Mattel executives said that Barbie is “not a feminist movie.” Margot Robbie later responded to the sentiment like, What do you mean? I think it’s a feminist film, and I think it certainly tries to be nuanced about what feminism means. Early on, the Barbies believe that they live in a feminist world. But their idea of feminism is flawed. They live in this world in which Kens are second-class citizens. There isn’t gender parity. The film wrestles with this glossy idea of feminism that a lot of young girls were sold. Being told that you can be anything is inspirational, but that’s not necessarily truthful. That debate is what the film invites you to think about, but at the same time, it’s squarely feminist.

Lora: You wrote a great article today about America Ferrera’s monologue, which was a striking moment in the film. How did a serious monologue about the challenges and contradictions of womanhood fit into a movie that also has a lot of dance routines and fun costumes and sparkles? Did Gerwig succeed in reconciling those energies?

Shirley: I think it was successful, because I don’t think a monologue that sobering would land the way it needed to land in a more sobering film. If the film wasn’t so high-energy and colorful and bombastic, then that monologue would have come off as didactic.

What Greta Gerwig has done is put this speech inside a Trojan horse of a film. In a meta way, that’s true to the experience that America Ferrera’s character is talking about. For women, in order to succeed, you have to constantly negotiate your power. Like, you have to play up this idea of not being too aggressive or threatening, so you have to giggle a little bit. You keep having to conform to these expectations of how women should act. Something that made me love that monologue—even if the things the character was saying were kind of obvious—is that there’s no grand takeaway.

Lora: I have to ask, where did “Barbenheimer” come from? Why is everyone talking about seeing Barbie and Oppenheimer back to back?

Shirley: The simplest way I can put it is that Barbenheimer is a phenomenon born out of the fact that two movies that seem diametrically opposed to each other in terms of style and function and perceived target audience are coming out at the same time. One is a grim, somber biopic about the father of the atomic bomb that is three hours long and comes from the quintessentially-boy-movie director Christopher Nolan. It has all these weighty considerations of morality, human nature, and hubris. And the other film, at least the way it’s marketed, is this glittery, poppy celebration of fun directed by Greta Gerwig, whose films have very much been about girlhood and womanhood.

Oppenheimer seems to be for those who want a film about reality, and Barbie seems to be for people who just want fantasy. I think that’s why people have had so much fun mashing them up and making memes about them. For all the dichotomies that these two films represent, though, I think they also share a lot of themes. They ask existential questions: How do we exchange ideas? What prevents us from becoming the best versions of ourselves? What makes us human?

Related:

Today’s News

- Former President Donald Trump’s classified-documents trial will begin in May 2024, despite his request to delay proceedings until after the presidential election.

- James Barber, who was on Alabama’s death row, was executed after the Supreme Court refused to block his execution following a series of botched lethal injections in the state.

- Police began making arrests related to a video that went viral this week depicting two women in Manipur, India, being sexually assaulted and forced to parade naked through the streets amid ethnic clashes in May.

Evening Read

The Real Lesson From The Making of the Atomic Bomb

By Charlie Warzel

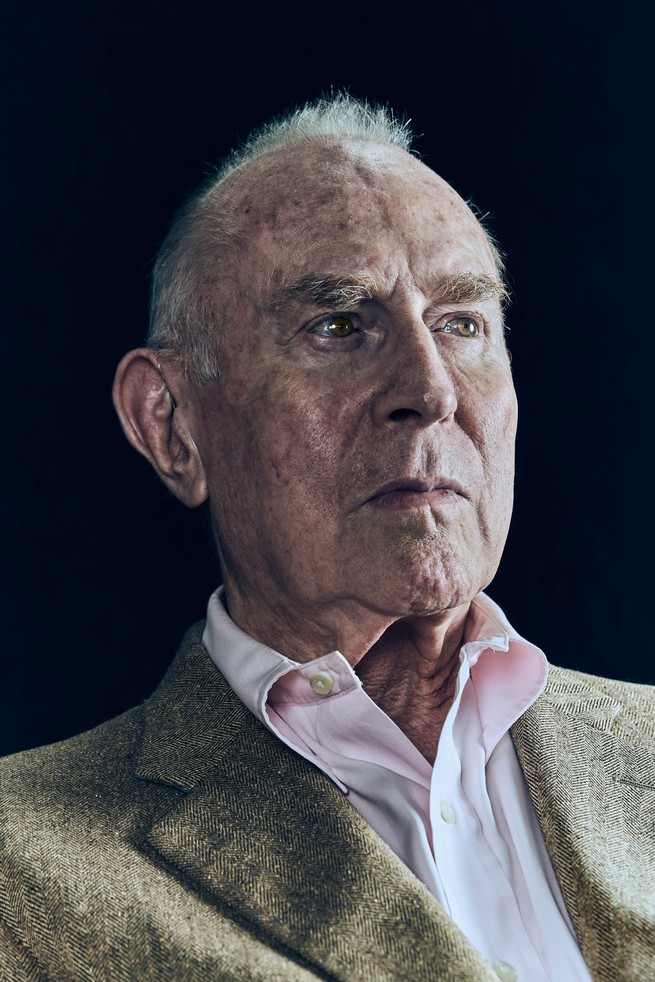

Doom lurks in every nook and cranny of Richard Rhodes’s home office. A framed photograph of three men in military fatigues hangs above his desk. They’re tightening straps on what first appear to be two water heaters but are, in fact, thermonuclear weapons. Resting against a nearby wall is a black-and-white print depicting the first billionth of a second after the detonation of an atomic bomb: a thousand-foot-tall ghostly amoeba. And above us, dangling from the ceiling like the sword of Damocles, is a plastic model of the Hindenburg.

Depending on how you choose to look at it, Rhodes’s office is either a shrine to awe-inspiring technological progress or a harsh reminder of its power to incinerate us all in the blink of an eye. Today, it feels like the nexus of our cultural and technological universes. Rhodes is the 86-year-old author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb, a Pulitzer Prize–winning book that has become a kind of holy text for a certain type of AI researcher—namely, the type who believes their creations might have the power to kill us all.

Read the full article.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. Crook Manifesto, Colson Whitehead’s newly released sequel to Harlem Shuffle, is both powered and limited by its most absorbing characteristic.

Watch. For the non-Barbie fans here, there’s always Oppenheimer, which is more than just a creation myth about the atomic bomb.

Play our daily crossword.

P.S.

I remember being a kid and watching a movie about the deep sea on 3-D in an IMAX theater in Chicago. We strapped on those nerd glasses and felt ourselves surrounded by fish and reefs. I took that experience for granted. So I was surprised to learn that there are only 19 movie theaters in the United States where you can see Oppenheimer in IMAX 70-millimeter. The Washington Post estimated that people in large swathes of the country are more than a three-hour drive from the nearest theater screening the movie in this format. Of course, the movie can be watched in other formats in various movie theaters. But Christopher Nolan told the Associated Press that when he shoots films such as Oppenheimer on IMAX 70MM film, “the sharpness and the clarity and the depth of the image is unparalleled.”

— Lora

Katherine Hu contributed to this newsletter.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest For Top Stories News Click Here