In between us and our architecture exists a landscape of public objects which, though solid, familiar and seemingly ever-present, remains strangely invisible. Who really notices the shape of a street light, the clusters of communications boxes, the text cast into manhole covers or the way people use a bench?

The erosion and privatisation of public space and the decline of the high street or main street has been much discussed. But street furniture, arguably the most public and civic of architectures, remains curiously unexplored. And it is rapidly and radically changing. The British street stalwarts of my childhood in the 1970s, the telephone boxes, newspaper kiosks and public lavatories are fast disappearing, overtaken by changes in technology or undermined by municipal spending cuts.

They are being replaced by a very different layer of public infrastructure, much of it to do with surveillance and control: street cameras and CCTV, big chunks of concrete and steel to stop truck bombs, seating designed to be inhospitable to the homeless, bus stops the prime function of which is to advertise to passing motorists. Street furniture has become an expression of alienation rather than amenity.

When Baron Haussmann smashed his way through medieval Paris in the 19th century, creating the formal city of avenues and elegant apartment blocks, he created an in-between landscape that mediated between the scale of the urban block and the human body. There were street lights and pissoirs, newsstands and benches, drinking fountains and advertising columns, an infrastructure of industrial iron which made the city between the buildings a more comfortable and accommodating place.

These urban objects even had their own portraitist. Photographer Charles Marville, who documented the changes in the Paris cityscape and the grandeur of the new architecture in the 1850s and 60s also meticulously shot these objects, most notably the elaborate street lights, as if they were figures in the city, giving them the dignity of cast-iron citizens. His photos of this infrastructure of public objects were exhibited around the world, promoting Paris as the ideal modern city.

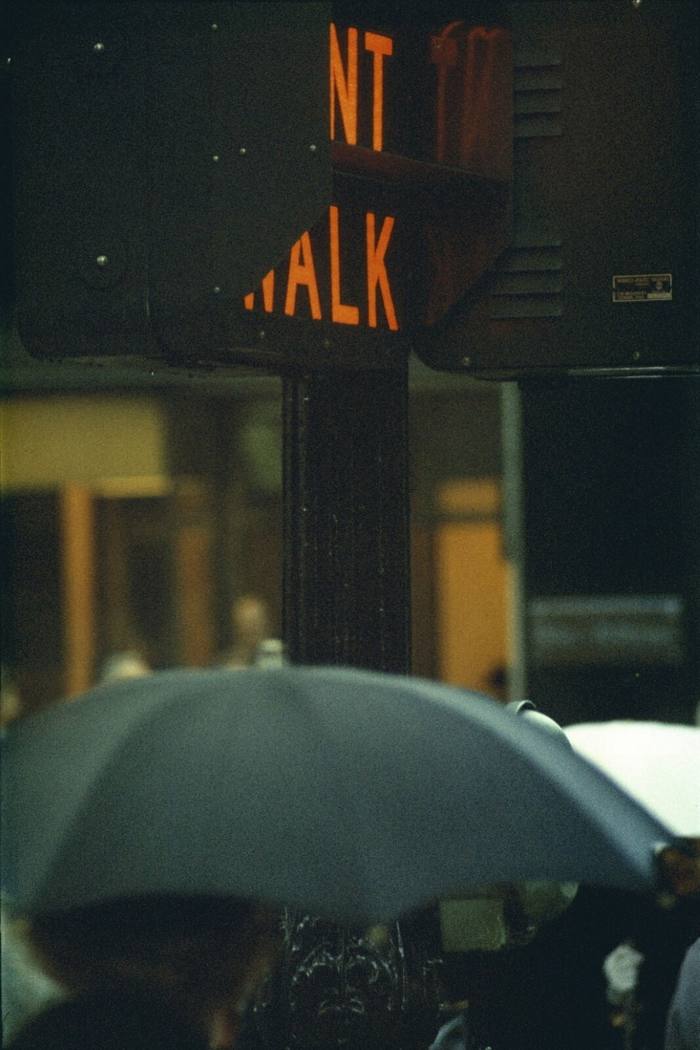

Photography, in fact, developed in parallel with the boom in street furniture: it is through photographs that we can begin to understand the growing impact of street furniture on metropolitan life. As cameras evolved, street photography, snatching images of urban life, Cartier- Bresson’s decisive moment, emerges as a form.

So often, it is the contrast between the fixed solidity of a street fitting and the mobility of the body which makes the shot. Stanley Kubrick started as a New York snapper and his 1945 shot of a dejected newspaper seller has it all; the headlines (“Roosevelt Dead”), the shock, the ennui, the ephemeral, the words and the face. The kiosk becomes a miniature theatre. Likewise in Helen Levitt’s magical 1988 shot of a family stuffed into a phone booth, the contrast between squishy bodies and inflexible box becomes farce.

In other instances furniture replaces the body, acting as a stand-in. =For André Kertész in the 1920s, the chairs of Paris parks become memories of a conversation, temporary traces of the bodies that earlier inhabited them. For Richard Wentworth, in 2001, the iron railing with a glove impaled on it becomes both display and surrogate hand, a strange and slightly sinister juxtaposition of two shiny black objects. The brilliant Vivian Maier and Saul Leiter found beauty in the banal: a doll in a trash can, the boiled-sweet colours of traffic lights seen through rain drops on a window.

These are things in dialogue with us, a world of objects made visible through our noticing the small interactions and the striking juxtapositions. Today, J Wesley Brown brilliantly captures the contrast between the aspirational messages of the ads which are now the raison d’être of bus shelters with the condition of those taking shelter, the desolate, the bored, the poor, the unseen. Here too the shelter becomes a Beckettian stage of endless waiting.

In a manner, the bench is the apotheosis of urban life, the city’s most democratic place and a forum from which to watch life happen. In a commercialised public arena in which we have become recognised as consumers and customers rather than citizens, the bench remains an unalloyed public good.

Yet even here we find the seats subdivided so that they become inhospitable to the homeless or the otherwise horizontal. Associations with queer cruising accelerated the decline of public lavatories as prurient councils looked for excuses to shutter them. A recent campaign saw London’s last surviving gaslights saved from conversion to cheaper LED and illustrated how emotionally attached we can become to the these fittings. They make our collective space.

The early days of the pandemic saw some curious anomalies, including benches taped off like crime scenes lest people should congregate. Then outdoors was declared better than indoors and the streets filled with new types of furniture. There were garden sheds repurposed as dining booths and streets temporarily pedestrianised by restaurants (which made cities feel alive again but also effectively privatised great swatches of public pavement). And it gave a huge boost to “parklets”. These hybrid bench/planter/pedestrianisation devices were originally developed in San Francisco as a witty way of recolonising parking spaces and they have taken off in a big way across the world.

Elsewhere, though, a new layer of communications kit has begun to clog our pavements. 5G masts as thick as tree trunks, mysterious pressed metal boxes clustered in groups, broadband boosters, air quality monitors, speed cameras, traffic cameras, a whole panoply of things that might make communication easier in the ether but which coagulate into ugly streets in which pedestrians are squeezed into ever tighter spaces.

Street furniture was once a form of branding; grand cast-iron street lights, elegant railings and fountains a marker of public prosperity. Think of London’s lipstick-red post and phone boxes, Parisian metro signs, New York’s helmeted hydrants. These small things define public life.

But now even Paris has succumbed to the commodification of street furniture. The city’s new newsstands lack the chaotic energy of the originals, the handbill-pasted Colonnes Morris replaced by illuminated versions carrying backlit ads for cosmetics rather than theatre and cabaret programmes. The beautiful Wallace drinking fountains still work, unlike London’s, which are mostly dry and clogged up with leaves and fag-ends. Their replacements, the bottle refill stations, which could have been beautiful civic moments in the public realm, instead manifest as garish plastic water-coolers like idiot urban emojis.

Yet many of the things in our streets continue to give pleasure and make the city richer — from the bouquiniste stalls lining the Seine in Paris to the hot dog and coffee stands in New York, which light up the streets before the day has started. Benches, bins and Belisha beacons are as much characters in the city as we are. Street furniture, that smallest and most public of architectures, continues to evolve, to shift in purpose and emphasis, defining and reframing our streets while we continue to walk on by, barely noticing.

‘On the Street: In Between Architecture’ by Edwin Heathcote is published by HENI

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here