Scanning all the media coverage of the leaked City Council audio — which at this moment seems poised to join Nixon’s Watergate tapes in the annals of recording infamy — it’s hard to decide which sections might be the most appalling. Councilmember Mike Bonin, who is gay, is dubbed a “little bitch.” The behavior of his adopted Black son is likened to that of a monkey. Jabs are exchanged about the child, with City Council President Nury Martinez cattily describing him as “an accessory.”

The conversation is grotesque — a furnace blast of racist tropes and unvarnished political sausage-making. It also surfaces a roiling debate about the nature of Latino identity and the blinkered ways that identity has historically been defined and wielded.

At one point in the recording, Martinez says of L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón: “F— that guy. … He’s with the Blacks.” The sentiment is echoed by Councilmember Kevin de León, who describes Bonin as the council’s “fourth Black member,” someone who “won’t f—cking ever say peep about Latinos.”

Elsewhere in the audio, Indigenous immigrants from Oaxaca also come up — literally — for denigration. Martinez describes them as “little short dark people” before dismissing them as “tan feos” — very ugly.

Martinez resigned from the City Council on Wednesday. The two other councilmembers caught on tape, De León and Gil Cedillo, have been subject to a growing chorus of calls for their resignations — including from the president of the United States. But whatever the fate of the various parties involved (Ron Herrera, of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, has also resigned), the comments reveal the insidious ways in which Latin America’s Black and Indigenous populations have been marginalized, their experiences overwritten by a vague pan-continental identity. It also marks an old way of thinking — part of deeply embedded systemic issues with which we have yet to fully reckon.

For one, the us-versus-them framing of Black and Latino political interests actively overlooks — erases — the fact that Latinos can be Black and Black people can be Latino. (Latino is a loose ethnicity, not a race, and the African diaspora spans the Americas.)

Approximately 1.2 million Latinos in the United States identify racially as Black, according to an analysis of census data published last month by the Pew Research Center. In Los Angeles County, according to 2021 census estimates, Black Latinos number more than 23,000 out of a total Latino population of 4.8 million. That’s small compared to New York City, where Afro Latinos, largely from the Caribbean, account for more than 113,000 out of the city’s 2.5 million Latinos. But neither figure includes mixed race statistics, which likely make Afro Latino representation higher in both regions.

If the Afro Latino presence in Los Angeles is small, it’s nonetheless one with deep roots. Afro mestizos from Mexico helped establish the city of Los Angeles in the 18th century. More recently, the Afro Latino presence is visible culturally in the works of hip-hop artists such as Kemo the Blaxican, whose songs engage the hybrid African American and Chicano experience in L.A., as well as writer and photographer Walter Thompson-Hernández, whose Instagram account, Blaxicans of L.A., began exploring the intersections of Black and Mexican culture half a dozen years ago. In 2020 and 2021, La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in downtown L.A. staged a long-term exhibition titled “afroLAtinidad: mi casa, my city,” which Thompson-Hernández helped organize. (The show’s impact, unfortunately, was blunted by the pandemic.)

Councilmembers Gil Cedillo’s and Kevin de León’s chairs sit empty at Wednesday’s City Council meeting.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

The erasure of Blackness within Latino identity long preceded Martinez. It’s part of a long-running tradition in Latin America.

In the United States, “Latino” has generally come to be equated with the vague adjective of “brown.” In Latin America, Latino identity — Latinidad — is frequently incarnated by the symbol of the mestizo, interpreted to be a person of mixed European (often Spanish) and Indigenous descent. In the essentialized form, the mestizo is someone who is of mixed race but adopts the culture and language of Europe. Brown — but not too brown. (In Latin America, issues of race tend to manifest in gradations of color rather than the Black/white binary that operates in the U.S.)

Rutgers University scholar Tatiana Flores goes deep on the roots of Latinidad in an essay that appeared last year in Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, a journal published by the University of California Press. As she writes: “mestizaje is a project that promotes the erasure of cultural differences in the service of the formation of a group identity.” Her work tracks the ways 19th century intellectuals sought to create a unifying identity that marginalized Indigenous ethnicities while pushing Black people completely off the page.

Status, as a result, has generally been conferred to those with the greatest proximity to whiteness. (It’s a system that benefits a fair-skinned mestiza like myself.) In Latin America, the term “mejorar la raza” — improve the race — means to make it whiter. The derogatory comments that Martinez, the fair-skinned daughter of Latino immigrants, leveled at other Latino immigrants — Indigenous Oaxacans — didn’t come out of nowhere.

It’s also a way of thinking that belongs increasingly in the past. The leaked tapes land at a moment when a younger generation of thinkers is challenging the very foundations of Latinidad.

In 2018, a popular meme created by Afro-indigenous poet and theorist Alan Pelaez Lopez critiqued the influence of white supremacy on Latinidad. The hashtag Lopez placed on the image — #LatinidadIsCancelled — went viral as a result. In the years that followed, that concept has appeared in media outlets such as Remezcla and on the Root, where contributor Felicia León examined why some millennials were rejecting the label wholesale, preferring to identify in other ways. Some Black artists, for example, have begun identifying as part of Afro Latino diasporas instead of assuming national or ethnic labels.

The uprisings for Black lives during the summer of 2020 placed Latinidad under further scrutiny, putting the vagaries of Latino racial hierarchies in the spotlight. When Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical feature film “In the Heights” debuted the following summer, it faced controversy over its lack of dark-skinned Afro Latino representation in the lead roles — an oversight for which Miranda later apologized.

These complex issues of identity were also at the heart of El Museo del Barrio’s 2020-21 triennial exhibition, “Estamos Bien,” in New York — which I wrote about at length for the New York Review of Books. That show embraced the fractures in Latino identity instead of trying to paper them over with some imagined concept of unity.

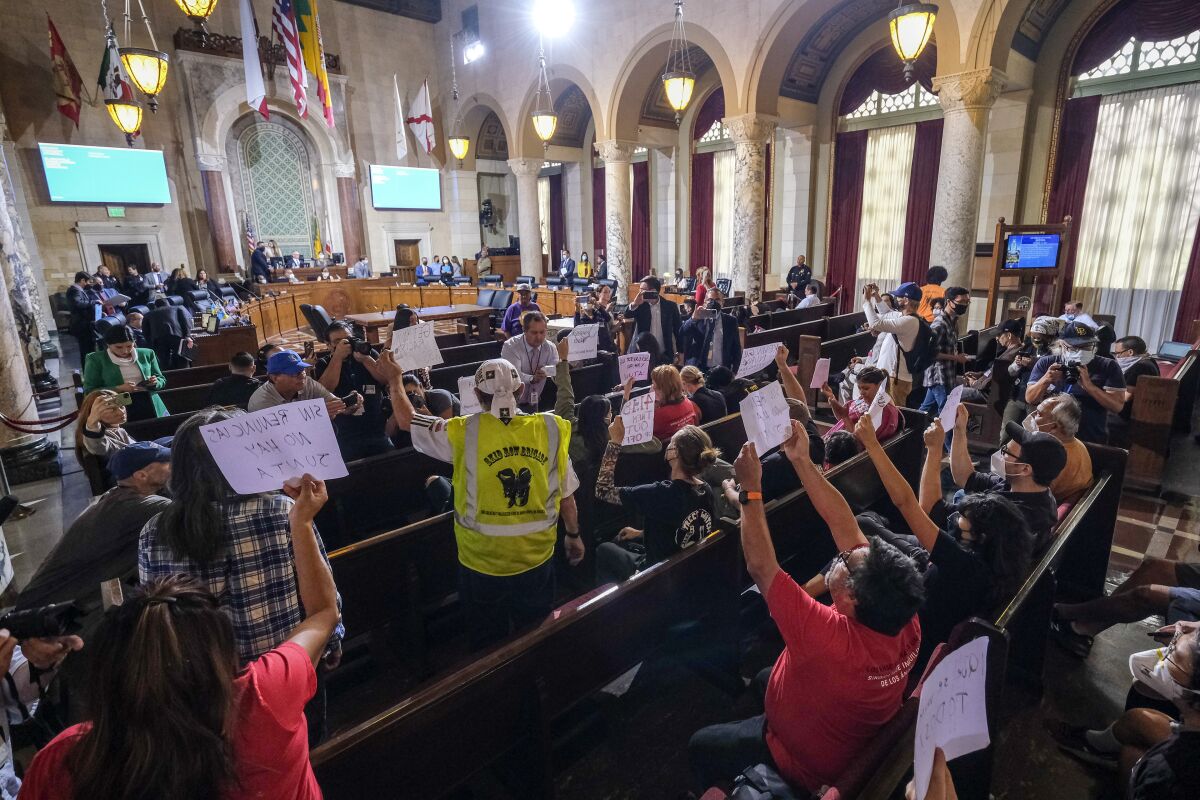

Protesters hold signs and shout slogans before the Los Angeles City Council meeting on Wednesday.

(Ringo H.W. Chiu / Associated Press)

It’s too early to tell what the City Hall scandal means for Latinidad as a concept. It is heartening, however, to see people of all races protesting the racist vulgarities.

On Wednesday, when Martinez resigned from her post, her mystifying resignation letter — a non-apology apology taken to epic proportions — closed with the line: “To all little Latina girls across this city — I hope I’ve inspired you to dream beyond that which you can see.” Martinez certainly inspired something — mainly, tweets like, “Girl WHAT?”

Those little Latina girls? Many of them are Black and Indigenous. An apology, perhaps, would have been more inspiring. Along with a role model who sees them not as adversary but as central to the story of who we are.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here