Majestic and inexorable, they rise on the tiered platforms of the Hayward’s vast opening gallery like actors in a classical drama. High at the back, surging across a screen, the singer Santigold is transformed into a monster: dreadlocks curling like tentacles, body dangling machine parts, she fills the skies, devouring flocks of birds, in Wangechi Mutu’s “The End of Eating Everything”. In the foreground, Mutu’s red soil, wood-entwined figure “Sentinel V” presides like a grotesque goddess — part Earth mother, part vengeful spirit.

You see her initially through a frame: entering the gallery you come straight up against Nick Cave’s monumental wobbly grid of linked black hands, stretching upwards, holding on tight. This is “Chain Reaction”, speaking at once of connections, collectivity, and imprisonment, cages, cycles of enslaved labour.

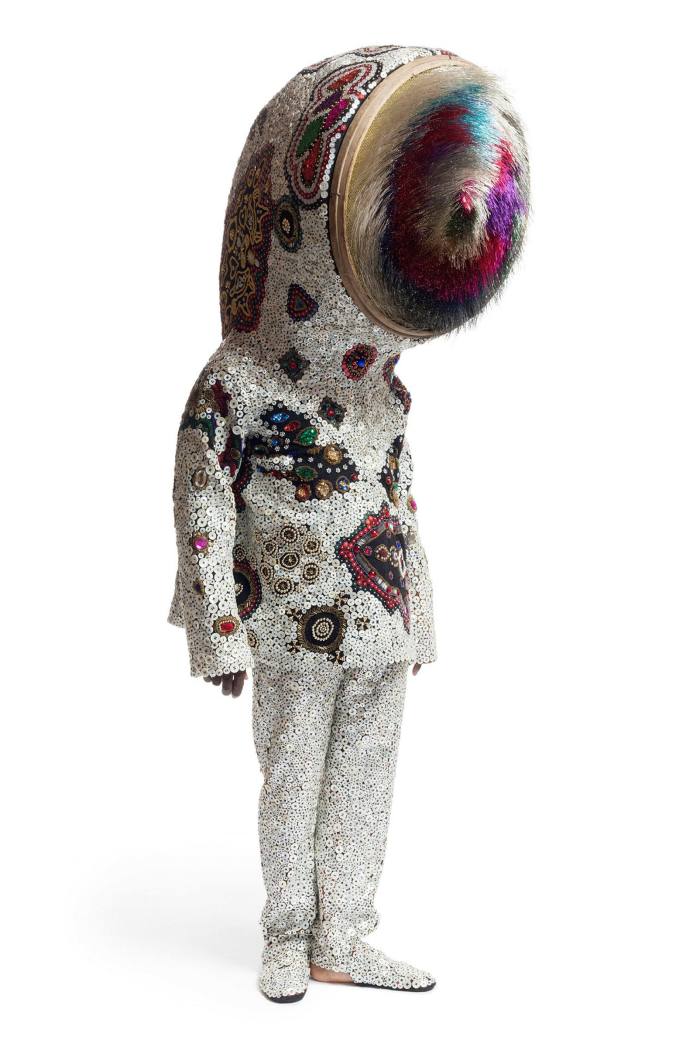

Dotted around the hands, a bright chorus, are Cave’s “Soundsuits”: jangling multicolour wearable sculptures assembled from feathers and twigs, sequins and beads. Encasing the entire body, they erase the appearance of race or gender. The staging, wonderfully disrupting the Hayward’s cool concrete geometry, announces from the first instant that its new show In the Black Fantastic is as electrifying and immersive as the title implies — and also that dark currents underpin the spectacular.

Cave began making his comically exuberant “Soundsuits” on hearing reports of police brutality against an innocent black man, Rodney King. His sculptures are about vulnerability; theatricality and masking are defences (Cave trained as a dancer).

In her “Sentinels” Mutu reshapes ancient weathered materials, witness to centuries of trauma, into “characters”, which, she says “speak of a place and a time. in the future when we are able to live in harmony with one another, in harmony with the land”.

Fantasy deflects horror and confusion by wild imaginative freedom. Alice in Wonderland responded to the bewilderment Darwin’s discoveries imposed on the Victorian mind. Kafka wrote Metamorphosis when a hostile society made him feel like an insect. So with the Black Fantastic, which curator Ekow Eshun defines as the “turn to the speculative” by contemporary black artists who “draw from history and myth to conjure new visions of African diasporic culture and identity”.

As if they have galloped across the bridge from his “Procession” at Tate Britain, Hew Locke’s “Ambassadors”, black statues in ornamental costumes on horseback, one-third life-size, are poignant, dignified, engrossingly individualised. One is decked out in a red turban and an embroidered bust of Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, another in Rasta canopy hat and William Blake’s print of a tortured slave. Carnival vibes cross with mimicry of stiff baroque carvings: these elaborately dressed personages are literally weighed down by the trappings of colonial history. Yet they march: Locke calls them “survivors, on horseback, in a dystopian burnt-out landscape, heading to the future”.

Black art on the move, creating fresh idioms, is a terrific, timely subject. Eshun’s show is visually stunning, intellectually cohesive, the Hayward’s open spaces and ramps allowing conversations, showcasing overlapping interests. A particular strength is linking black magical realism in visual art to film (there’s a complementary season at the BFI next door) and music within the Afrofuturist movement, including several direct collaborations.

Lady Midnight’s ragtime, soul and rock score adds melancholic/defiant strains to Kara Walker’s stop-motion animation “Prince McVeigh and the Turner Blasphemies”: leaping shadow-puppets enact the recent white supremacist atrocities of Timothy McVeigh’s Oklahoma City bombings and the 1998 lynching of James Byrd, Jr. The shock of violence is intensified by the chasm between terror and the silhouettes’ delicate, dancing fluidity.

Uneasy beauty wrought from horror is there too in Ellen Gallagher’s “Watery Ecstatic” series, sumptuous evocations in pools of saturated colour of a submarine realm of hybrid amoebae/aquatic plants/human creatures, and “Ecstatic Draught of Fishes”, underwater female figures based on queenly African Fang carvings. Gallagher’s narrative source comes from 1990s Detroit electro- techno music duo Drexciya, who proposed an origin myth of an underwater species descended from pregnant slaves thrown overboard during transatlantic deportation — a flourishing alternative to America’s tragic history of slavery.

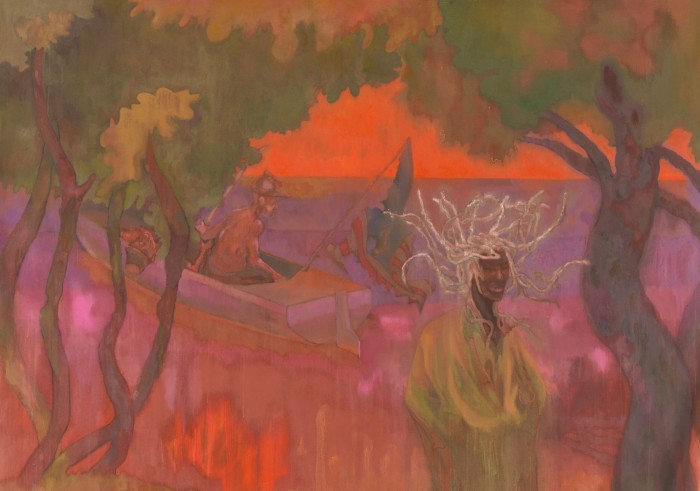

While Mutu’s, Cave’s and Locke’s top-heavy, grounded sculptures reign downstairs, Walker’s and Gallagher’s spectres are part of a more flowing installation upstairs: shape-shifting figures and morphing landscapes in multiple media. Cauleen Smith’s “Epistrophy”, named after a Thelonious Monk composition, projects Nasa videos of the Earth and landscape photographs across a table top still life of symbolic objects — statuettes, jewellery, a stuffed raven — which cast shadows across the rushing scenery: improvised, jazzy, kaleidoscopic. Chris Ofili’s black Odysseus swoons to an emerald mermaid, tail whipping up the waves, in “Kiss”, a painting as sinuous and sexy as Klimt’s. A water-speckled cast of metamorphosing characters star in his “Odyssey 11” and “Calypso”.

Mining the language of decorative modernism, Ofili continues to influence contemporary black figuration significantly — its dreamy scenographies, storytelling energy, stately female figures, as evidenced by two gifted younger painters who are this show’s revelations.

Sedrick Chisom’s phantasmagorical swampy colourfields look limpid but have heavy titles telling of rampage: “Medusa Wandered the Wetlands of the Capital Citadel Undisturbed by Two Confederate Drifters Preoccupied by Poisonous Vapors that Stirred in the Night Air”; “A Blighted Cavalryman Patrolled the Valley of the Rocks on His Worn Out Horse Through Dead Mist at Miasmic Ass-crack Hours”. Chisom’s satirical epic envisions a scenario where all black people leave Earth, and the remaining population, succumbing to a skin-darkening plague, fight it out according to shades of colour.

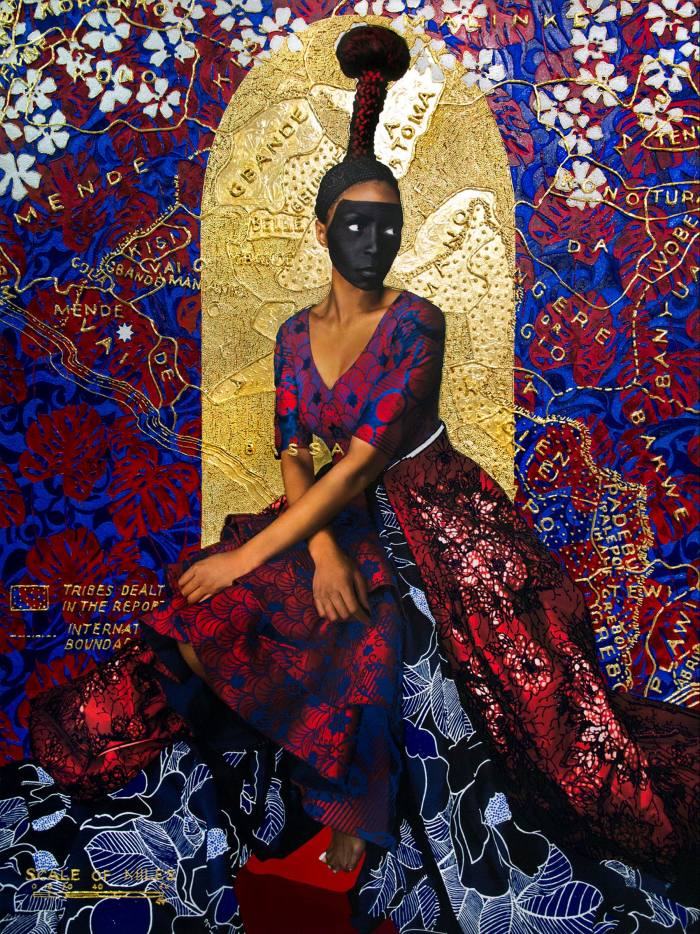

Enlarged to billboard scale on the Hayward’s exterior is a statuesque black-masked woman posed against a golden ground, staged like a fashion shot, from Lina Iris Viktor’s collage series “A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred”. Close up, Viktor’s lavish textures mesmerise: maps of west Africa and its rivers streaming in 24-karat-gold are superimposed on printed, painted figures and, in one lyrical image, on a palm tree, shaped like a woman in a wide dress, spreading over cobalt seas. The historical mapping is of gold trade exploitation — yet Viktor reclaims heart of darkness tropes with glittery assertions of youthful black power and growth.

“But where is your Renaissance?” the white master asks the slave in Derek Walcott’s “The Sea is History”. “It is locked in them sea-sands,” comes the reply, and “in the salt chuckle of rocks/with their sea pools, there was the sound/like a rumour without any echo/of History, really beginning”. Eskow’s show suggests something like that possibility: artists answering one negative fantasy, “race as a socially constructed fiction” with their own imaginings, rethinking the past, reconfiguring the future. It’s an exhilarating vision.

To September 18, southbankcentre.co.uk

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here