There’s an image that comes to mind when one hears the words “Punjabi man”. It’s reinforced by films, ads, music videos and other elements of popular culture.

In this imagining, the Punjabi man is a strapping fellow, vrooming past fields of mustard in a fast car, drinking large glasses of lassi and cheerily doing the bhangra. Ending sentences with war-like phrases such as “chak de phatte” (“toss the planks”), which today just means “let’s get going” but was once a war cry, as Mughal-era Sikh armies swept the north, destroying enemy bridges and tents as they rode from one victory to the next.

What do you do, in this milieu, if you’re not a plank-tossing, fast-riding “man’s man”? What happens if you’re slim, lithe, physically weak?

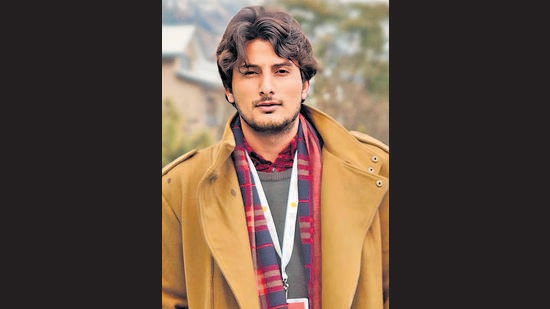

Debutant director Anmol Sidhu’s film Jaggi (2021) offers a raw, brutal answer. The titular protagonist (a searing performance by debutant Ramnish Chaudhary) is a slim, lithe, physically weak teen who is repeatedly raped, beaten, bullied and ridiculed. Brutality and sexual repression emerge as undercurrents in the jovial bands of merry macho men.

The reality of his film, says Sidhu, 28, was the lived reality of boys who didn’t fit a narrow hyper-masculine norm in the rural Punjab where he grew up. The lack of sex education, coupled with gender segregation and a wide generation gap, especially in rural areas, mean that “between the ages of 12 and 16, their hormones are raging but boys have nowhere to turn for information or solace,” Sidhu adds. “I’ve seen boys who were considered ‘soft’ or ‘weak’ become victims of abuse by older boys. There were boys who would be picked up by seniors almost every single day. Elders and authorities tend to turn a blind eye because ‘we don’t talk about sex’.”

Jaggi struck a chord at its premiere at the Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles in April, winning the Audience Choice Award for Best Feature and the inaugural Uma da Cunha Award for Best Feature Film Debut. “Few independent films in India are made in the Punjabi language and fewer still find their way into festivals to reach a wider audience. This film needs to be seen in a milieu where sexual matters tend not to be addressed openly,” film programmer da Cunha, also a founding member of the festival, said in a statement.

Tell-all tales

Sidhu began writing the script for Jaggi in 2018, struck by two stories he encountered that year, about young men who were abused over time and died by suicide or lashed out in violence.

Made amid the pandemic, in 2020-21, Jaggi was a struggle on numerous fronts. Sidhu started out without a producer, using funds borrowed from friends and relatives, including cousins settled abroad. His then-fiancé-now-wife Shefali Sood, 30, a corporate executive, contributed too. She even agreed to advance their wedding date so he could add their cash gifts to his kitty. “He was so passionate that I just knew that I had to help him work towards his dreams,” she says.

The cast and crew were all first-timers. Sidhu found the actors, including Chaudhary, among his juniors at the Alankar Theatre Group in Chandigarh. “The first lockdown was announced almost immediately after Ramnish came on board. So he lived with me for almost six months in Kauloke,” Sidhu says, referring to the village where he grew up, and where most of the film was shot. “He learnt to milk cows, cut fodder and work in the fields, so that it would look authentic when we began shooting.”

Even as his lead was preparing, Sidhu maxed out his credit card to buy a camera, then hired a wedding photographer from a neighbouring village as his cinematographer. “Karan Dhaliwal had to learn the technical things like framing and symmetry. It took him a few weeks,” Sidhu says.

Because of the nature of the theme and content, he still hasn’t shown the film to his family. “They are aware and very proud of all the praise it’s getting,” he says. Meanwhile, as Jaggi travels the festival circuit, Sidhu retains his job as a documentary director and writer of memes with a digital-marketing agency. It’s a job he’s had for three years; a compromise he reached with his family. “I wanted to do theatre in Chandigarh full-time,” he says.

He’s already thinking about his next film. It will explore the dark and risk-filled lives of female dancers in Punjabi wedding orchestras. “Most Punjabi films are comedies, with a handful of gangster films. They all stereotype Punjab,” Sidhu says. Part of what drives his choice of subjects, he adds, is frustration at these overused clichés.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here