There is a story that John Williams was working on Schindler’s List when he suggested to Steven Spielberg that he needed a better composer for his overwhelming Holocaust drama. “I know, but they’re all dead,” replied the director.

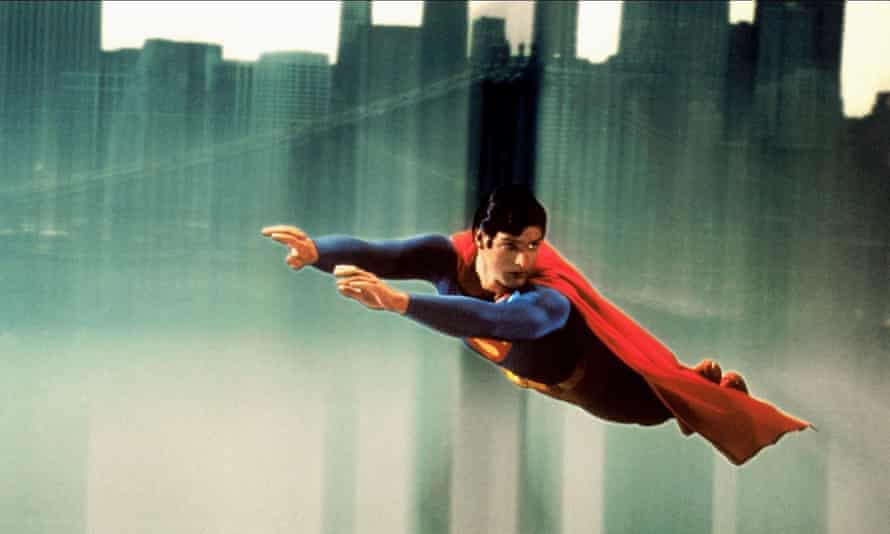

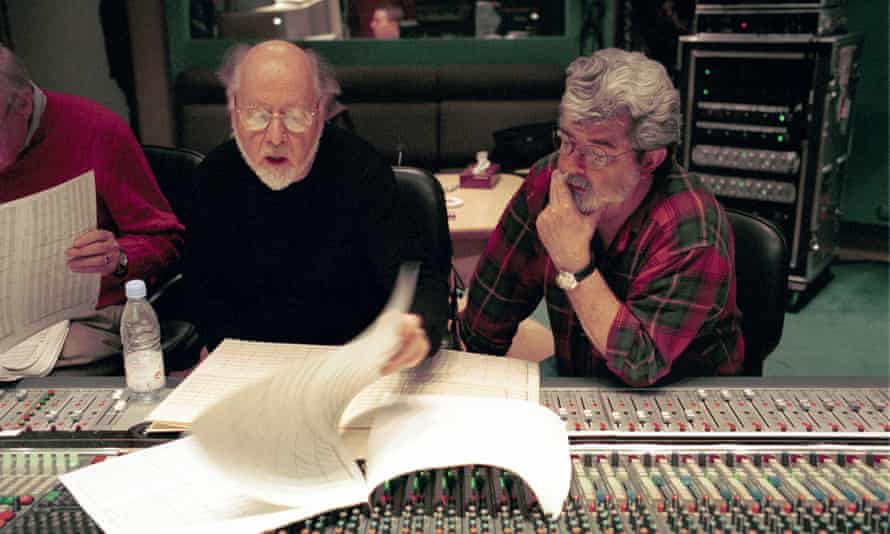

The anecdote is redolent not only of Williams’s humble view of his handiwork but also speaks to the traditional gulf in perception between the populist Williams – he has the most entries of any living composer in Classic FM’s hall of fame – and the vaunted masters of classical music. Celebrating his 90th birthday on 8 February, Williams’s film work encompasses blockbusters (nine Star Wars movies, four Indiana Joneses, three Harry Potters, two Jurassic Parks and the first Superman film) and serious historical fare (JFK, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Lincoln).

The stats are impressive. A 28-film, nearly 50-year collaboration with Spielberg. Fifty-two Oscar nominations – the most for a living person and second only to Walt Disney – with five wins. Four Olympic Games fanfares. One presidential inauguration (Obama). For all his accomplishments, Williams has always been undervalued by the classical establishment. But with the children weaned on Williams now old enough to be composers, musicians, critics and scholars, that is finally changing.

“I was immediately smitten by the leitmotifs,” says the virtuoso violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, about seeing Star Wars for the first time in 1978 in the Black Forest. “Looking back they still hold up; all these characters [are] elevated by his inventiveness. Usually, you would go to the cinema to see the actors. I would go to hear John Williams’s music.”

“As we reach his 90th birthday, I think the people who just go: ‘Oh, they all sound the same,’ just can’t justify it any more,” says the London Symphony Orchestra’s first violinist Maxine Kwok, who was inspired to join the LSO because it was the orchestra that performed the Star Wars score. “You can play the first two bars of Superman, Indiana Jones, Harry Potter and ET and people recognise them instantly. They are all different but by the same man.”

Subordinate to images, often buried under sound effects, film music is often seen as the neglected step-child of the classical world. But even among such cultural elitism, after the success of Star Wars, Williams in particular came under attack for being over-sentimental, simplistic, manipulative and a pasticheur – or worse, a plagiarist. You can easily fall down a YouTube rabbit hole watching videos comparing his music to the classical greats, be it Star Wars (Korngold, Holst, Stravinsky), Superman’s Love Theme (Strauss) or ET The Extra-Terrestrial (Howard Hanson). Film music scholar Frank Lehman says: “The examples that are often enlisted pointing to Williams’s influences are often pretty superficial, and used as a kind of gotcha.” The broadcast and film concert producer Tommy Pearson suggests Williams makes a deliberate artistic choice to lean into classical and film music idioms as a means of making the exotic, alien worlds of Star Wars feel more familiar.

“One of the key elements of Williams’s skill is the absorption of his tradition,” says Pearson. “He writes with counterpoint and harmony – all those boring traditional techniques that make him a great composer. He is so much smarter than his critics. If he sounds like Strauss, it’s because he wants to sound like Strauss. It’s not by accident. The groundwork is there in his skillset.”

There has always been another barrier to serious consideration. “The one thing he does so amazingly is create memorable tunes,” says Jess Gillam, who played Williams’s alto saxophone concerto Escapades at the 2017 Prom dedicated to his work. “He is a master of melody.” This supernatural sensibility for a memorable theme has seen him change a director’s mind – when Spielberg suggested the musical signature for Jaws should be a melodic counterpoint to the hulking great white shark, Williams played him that now iconic der-dum repetition – but it remains a lot of hard graft to craft something that feels as if it’s been with us for ever. “He’ll claim crafting melodies is actually the part of composition that he pours the most effort into,” says Lehman. “Sometimes it’s just a very short little motif, but to absolutely lodge them into your brain requires an incredible amount of care, revision and rewriting until you sand down the rock into a perfectly carved jewel.” The themes may be succinct, but they are not easy. “Schindler’s List is quite a simple line of music,” says Gillam, “but very demanding to execute with the emotion and the right style.”

Behind the headline themes is a wealth of writing featuring daunting technical challenges for the most proficient musician. “When you record a soundtrack, you don’t see the music until the day,” says Kwok. “Hedwig’s theme from Harry Potter was so tricky. It’s full of fast notes, sweeping sounds and an incredible series of scales. I remember going to the listening booth thinking: ‘Gosh, I hope that was all right.’” Another Harry Potter passage, a ridiculously complicated flute solo from the Prisoner of Azkaban, is so demanding and virtuosic it is now a standard audition-piece for orchestras recruiting new flautists. “His use of the palette of the orchestra is a really extraordinary thing,” says Gillam. “He knows the extremities of instruments, when to push to get these colours. For me that’s when the music comes to life.”

Since the 90s, Williams’s reputation has been bolstered by collaborations with superstar soloists such as the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, violinist Itzhak Perlman and more recently Mutter, who have all interpreted Williams’s work away from the movies. “I would love for us to delve deeper into the music he has written for violin, flute, cello,” says Mutter who premiered Williams’s Violin Concerto No 2. “He creates incredibly complex cadenzas for the solo violin. The whole musical structure is really on a higher level, as is everything he writes. We are not doing his genius justice by looking at one part of his oeuvre.”

“His music suits being performed in a concert hall,” says Pearson. “So much film music does not. Also, he writes for a traditional orchestra, which makes it much more compact and easier to perform. He is box office – his concerts always sell out – and he is the only one.”

Meanwhile, Williams’s scores for Jedi, wizards, and archaeologists have become a field of academic study. In 2018, Lehman, an associate professor of music at Tufts University in Massachusetts, created a comprehensive catalogue of Star Wars themes, detailing more than 60 leitmotifs and musical ideas from the nine-film space saga (and beyond), an act of academic erudition usually reserved for those long dead. “Every now and then someone will say: ‘This is a great analysis, but why don’t you turn to Wagner or Puccini? Why are you spending your time on this?’” says Lehman. “One answer is: “How much ink has already been spilled on Wagner and Puccini?’ Let’s concentrate on something new that has a vivid relevance to a lot of people these days.”

Williams shows no signs of slowing down, and is now at work on the fifth Indiana Jones film. If the symphonic tradition he reintroduced to movies in the 70s has been ousted as the dominant mode in Hollywood film-scoring by Hans Zimmer’s synth-driven mood-pieces, his work has a deeper, longer-lasting legacy.

“He has this unique ability to tap into the absolute correct emotion at the right time,” says Kwok. “It’s not dumbed-down music at all because, if it was, it would never have lasted. He has the knack of how to score music that creates a visceral reaction – without any action on screen.”

“For five decades he has touched people around the world. That is spectacular,” says Mutter. “But that is him: a unique gift to the world.” The Force will be with him, and us, always.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Music News Click Here