A young woman in a long white gown stands erect on the beach, one sandalled foot resting on wet sand. In the lushly black-and-white photo, her columnar body rises past frothing waves and the stiller sea beyond, to a strip of dark horizon. The frame cuts off her head and, as if to compensate, a beaded gourd dangles from her fingers; you can almost hear the instrument’s watery rattle against the rhythm of the surf. In the background, a swimmer’s dark arms lunge across the surface of the water; closer in, a lady in a white bonnet splashes in the foam, her body hidden by spume. The photo vibrates with the things we cannot see.

Bar Beach in Lagos, Nigeria, where that photo was shot in 2010, no longer exists. “It is now a building site,” the artist Akinbode Akinbiyi informs us on the audioguide for MoMA’s New Photography 2023 exhibition. “That stretch of beach has literally disappeared. Moments really are fleeting. That’s why I think photography can be very helpful, because it reminds you of what was.”

A powerful riptide of nostalgia runs through the whole show, which focuses on one of Africa’s most immense, ceaselessly expanding, moulting and self-erasing megalopolises. Bar Beach is haunted — by the political prisoners and criminals who were executed there in the 1970s; the crowds who gathered to watch the firing squad; all those who also came to swim, pray, sell food or gaze out across the Atlantic. Akinbiyi started going there in 1982 and returned regularly, until the shoreline was obliterated by the still unfinished new city-in-a-city, Eko Atlantic.

A sense of ritual and ceremony suffuses his photos, which are rich in tension even when their subject is repose. A dog slumbers in the sand while two men stride past gripping long staffs, as if on their way to part the waters. A white couple sits side by side on wooden chairs, as two black youths in white shirts — one on horseback, the other on foot — canter off in opposite directions.

These pictures benefit from the mystery that surrounds them; the rest of the exhibition could use a stronger dose of context. The seven photographers included here all have some connection with Lagos, though they have scattered across multiple continents. The show combats change with reflection, answering the city’s convulsive growth with calm meditations on the past. And yet, frustratingly, we’re not given enough information to understand where, when, why or how most of these pictures were taken, or what submerged currents of significance they invoke.

The psychologist and architectural photographer Amanda Iheme, for instance, excavates the inner life of aged buildings, looking for meaning in their ruination. “Buildings, the same as humans, have the experience of change,” she says, wisely. A text panel teases us with subtext: “For the artist, the physical condition of this architecture — much of it a product of Lagos’s Afro-Brazilian culture and British colonial history — testifies to contemporary attitudes towards the city’s past, which range from reverence to apathy.” This is where some narrative background would be useful, or at least a little insight into the specific urban richness lurking in abstractions like “culture”, “history”, “past” and “attitudes”.

In the 19th century, west Africans who had been kidnapped, enslaved, sold on in Brazil and eventually freed began returning to Lagos in numbers large enough to shape the city’s vibe. Iheme lingers on one evocative but now vanished relic of that era, the Casa da Fernandez or Ilojo Bar. The graciously neoclassical 1855 palazzo, which looked like it could have been transplanted from any colonial city in Latin America, was declared a national monument — and then abandoned to a lively form of decay.

Iheme lovingly captures the leprous facade, with its stripped plaster, wobbly railings and listing walls. “That same place where people were held as slaves in chains before they were taken across the Atlantic, 200 years after that now, people have markets inside here,” she marvels on the audioguide. “Can you just see how time moves?”

Sometimes it lurches — brutally. In 2016, bulldozers showed up unannounced and tore the whole structure down in a single day, an act of violence that followed decades of neglect and was answered by impotent indignation. “This building is a remembrance of what our ancestors went through in slavery and how they triumphed, came back and they showed that they were well-to-do,” a government minister intoned over the pile of rubble. Iheme salvaged a lone brick, and photographed it in close-up, making the fragment look every bit as imposing as the landmark it stands in for.

Her photos of another crumbling monument, the Old Secretariat Building, are even more eloquent of the city’s selective amnesia. A 1906 British colonial mash-up of dignity and whimsy, with a pair of pink belltowers sandwiching a peak-roofed temple front, the complex still stands — barely. Iheme focuses on the building’s half-shadowed interiors — a gloomy stairway leading down into a glowing puddle of light; disused furniture stacked in a yellow chamber, awaiting either redemption or destruction. These are the messy piles where Lagos stashes its splintered recollections as it hurtles towards the future.

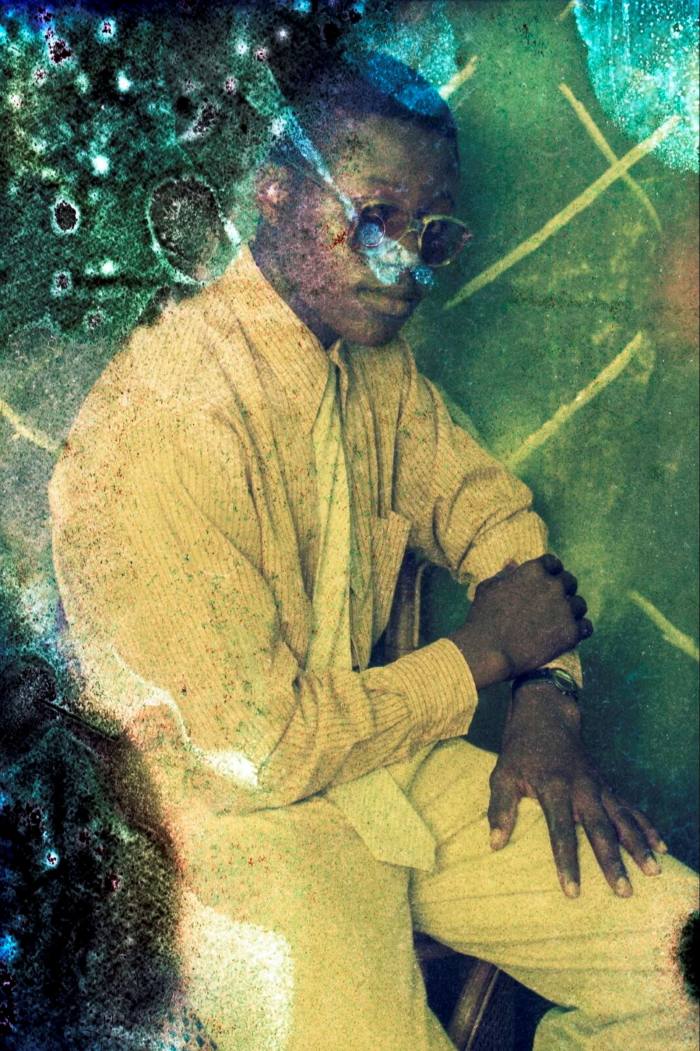

In a series called The Archive of Becoming, Karl Ohiri burrows into forgotten storerooms to discover unsuspected beauty in images that nobody had bothered to protect. He collected negatives that were shot in commercial studios and then left for years, perhaps decades, to be ravaged by heat and humidity. Ohiri’s artistry lies in finding, scanning, choosing and printing portraits of fashionable Lagosians who perform versions of themselves for a distracted posterity.

A boy in white trousers, white tie and pale seersucker shirt adopts a studiously casual pose. A parade of deliberate smiles, awkward embraces, squirming babies, glimmering dresses, patterned robes — all that crafted self-presentation dissipates in the mildewed frame. This poetic archaeology, with its amoeboid blooms and splashes of colourful decay, replaces the formal portrait with a hybrid creation, part memory, part ghost. Smears and splodges appear as bruises left by time.

In a similar vein, Kelani Abass mines his family’s old albums, cutting and pasting them into wooden letterpress frames. The years have done their work here too, fading bright clothing and clear outlines to a sepia blur. Casual snapshots morph into sculptural relics of a 20th century when many Africans cheered their nations’ independence movements and looked to the future with brittle hope.

If Nigeria’s capital still cranks out spasms of bold optimism, they’re not visible in this gentle, backward-looking show. Logo Oluwamuyiwa’s black-and-white photos do capture the city’s vitality, but in a throwback style that recalls Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. The formal experimentation has a stately, old-fashioned quality. Overlapping planes condense into flat surfaces, fragments of motion snap into coherent compositions and a self-portrait in a car’s wing mirror pays frank homage to the old masters of such techniques. And maybe that’s exactly what a metropolis in the throes of tumultuous change needs: a chronicler with a classic touch.

To September 16, moma.org

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here