Change was the only constant for the American artist Martin Wong. “Everything must go,” he declared in the press release for a 1986 exhibition, where paintings of shuttered storefronts in New York’s Lower East Side were his latest memorials to a city in flux. Wong saw himself in that unstable landscape. Dilapidated tenements and neglected streets were stages for the rich universe of his imagination. It was these marginal spaces on to which he mapped his myriad identities.

An exhibition at Berlin’s KW Institute, arriving from Madrid and travelling to London and Amsterdam later this year, brings the first major retrospective of the artist’s work to Europe. Malicious Mischief provides a crackling overview of the key themes of his career from the late 1960s to the 1990s. First in California, then in New York, he depicted Puerto Rican neighbourhoods, prisons, addicts, firefighters, friends and lovers who would succumb to Aids, before he too eventually died from an Aids-related condition aged 53. Before his death, though, he devotedly immortalised a pre-gentrified city. Brick by brick, he enshrined himself within it with his magical-social realism.

Born in 1946 in Oregon, Wong grew up in San Francisco, the only child of Chinese-American parents. An openly gay man in a society where Asian people were usually only represented through the racist, kitsch lens of Hollywood, perhaps it was a lack of visibility that pushed him towards visual art, self-taught in painting and later with a ceramics degree at Humboldt State University.

An early self-portrait shows how Wong eschewed stereotypes from the get-go. Dressed in a cowboy hat with long black hair, his look is fittingly multi-layered for an artist whose inspirations spanned Chinese calligraphy, Buddhist tantric art, astrology, graffiti and more.

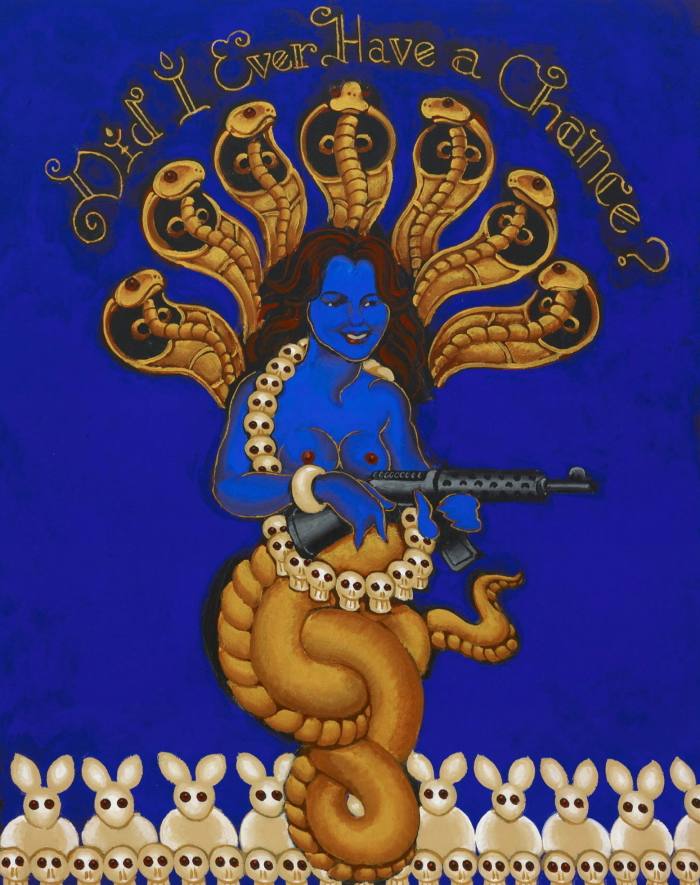

This bevy of sources hits you like a desert storm. In works of the 1960s and 1970s, full-blown Californian psychedelia meets Asian mysticism. This fugue of trippy visuals — a Magic 8 Ball surfing on a smouldering wave of flames and smoke (“Tell My Troubles to the Eight Ball (Eureka)”); a fire-hydrant-red demon gorging on a watermelon (“Tibetan Porky”) — could only be the work of someone who had fully embraced their outsider status. Like his insatiable deity, Wong possessed a hungry eye, constantly on the lookout for new material.

This paves the way for the intoxicating fusion of the surreal and banal in his landscapes. The first of these on show, “Weatherby’s”, was painted in Eureka, the sleepy northern California town where Wong occasionally escaped the hubbub of his Haight-Ashbury apartment. It shows a dreary commercial road transformed into an acid mirage. Lined with seafood joints and motels, the street radiates with the tacky neon signs that Wong loved. Licks of white paint conjure an electric sky vibrating overhead. Marshmallow-like cars seem to melt into the ground. As an urban chronicler, Wong had found his groove: teasing the fantastical out of the prosaic.

But this phantasmagoria vanished with a move to New York in 1978. Wong got a job as a nightwatchman at Meyer’s Hotel on the Lower East Side, ushering in a new era of nocturnal scenes characterised by his ubiquitous ochre bricks. With obsessive detail, he set about capturing his rundown surroundings through paintings of bricked-up windows, fire-damaged walls and ruined buildings.

In these worn settings, however, Wong makes room for poetry and romance. “No Es Lo Que Has Pensado” (“It’s Not What You Think”) depicts two figures embracing among the debris beneath a block of flats, oblivious to the blood-red sky signalling an unknown danger above them; in “Everything Must Go”, a sky adorned with astrological constellations unfolds over a pile of rubble. For Wong, demolition and decay formed part of a unique cosmic vision.

There’s space for desire, too. The exhibition underscores how Wong encoded his sexuality into his subjects, first in the hunky bodies of men in uniform and later in the sculpted figures of Latino inmates in his gritty prison paintings. Although these images come off as fetishistic, it shows how freely the artist expressed his own queer identity through different personas, ethnicities and cultures.

The 1980s were a time of discovery. Wong met and fell in love with the poet and ex-con Miguel Piñero, moved to the Hispanic neighbourhood known as Loisaida, taught himself American Sign Language, and stuffed all these into his paintings. But he could never shake off the disquiet he felt by the gentrification of his surroundings.

The large canvases of the shuttered storefronts painted for his Last Picture Show in 1986 recreate a Loisaida street in the gallery’s main atrium, rusted iron gates and padlocked facades sending the message “going out of business”. These paintings were made eight years before Wong was diagnosed with Aids in 1994, and it’s hard not to look at them with a double sense of loss: a view of the city before it was gone, not long before its viewer was gone, too.

Wong was also looking back in his final days. The show ends with his Chinatown works, where the artist revisited his childhood and the euphoric style of his California period. Although he disdained any reading of his work as merely a product of his Chinese heritage — he once wrote furiously in a notebook that he would never “be caught dead being an Asian American” — here Wong embraces the stereotypes of popular imagination. “Grant Avenue, San Francisco” (1990-92) projects a view of the city’s Chinatown like a Hollywood set, exotic architecture studded with 1930s characters. But in the crowd, Wong has placed his Aunt Nora as a coiffed figure in the foreground, behind her a portrait of himself as a young boy. Past and present, real and imaginary converge to create a collage which is as much personal as pop culture.

Like the urban landscape, Wong understood that identity wasn’t a fixed quality, but something that shifted, multiplied, was razed and rebuilt. Everything must go. In Wong’s art, a declaration of insolvency is transformed into a philosophical mediation, something phoenix-like and life-affirming.

To May 23 at KW Institute, Berlin, kw-berlin.de; June 16-September 17 at Camden Arts Centre, London, camdenartcentre.org; November 4-April 1 2024 at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, stedelijk.nl

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here