The sense of loss experienced after finishing a book.

The loneliness of having to keep a secret .

The anxious excitement of introducing a friend to something you enjoy.

There’s a word for each of these, in American author John Koenig’s extended version of the English language. (The first is looseleft; the second hiddled, from the Old English hidil, for hiding place; the third, licotic, from the Old English licode, for pleasing + the English psychotic).

In November 2021, Koenig released a book titled The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (Simon & Schuster), a collection of hundreds of such words created by him over 10 years. Each indicates some little ache, joy, urge or emotion that is experienced in daily life but rarely acknowledged, and for which the English language had no name. The book spent a while on The New York Times bestseller list.

“A lot of life is lived alone in our heads, and language doesn’t often cover those moments,” says Koenig, 39, also a graphic designer, video editor and voice-over artist. “The response to this book of musings has taught me that I am not strange for ruminating over these complicated emotions that aren’t easy to talk about. There are many others who feel this way, and that makes me feel far less alone in the world.”

The idea for the book popped into his head in 2006. By 2009, he was fascinated by the concept of creating a glossary of new words that would attempt to map the wilderness of the human mind. He began by posting his first few words on Tumblr.

The word “sonder” (the realisation that each passerby’s life is as vivid and complex as one’s own; see the glossary below for more) was his first big hit. It has 45,000 notes (reblogs, likes and replies) on Tumblr, and the response to it led Koenig to begin posting explainer videos about his words on a YouTube channel he set up called Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows.

Koenig’s first few words were comedic: zielschmerz, for the dread of finally pursuing a lifelong dream that actually puts one’s true abilities to the test (from the German ziel or goal + schmerz or pain).

Then came scabulous, for the feeling of affection we have for our scars, despite them being reminiscent of pain. Scabulous gave way to gnossienne, the awareness that someone one has known for years still has a private and mysterious inner life (from Greek gnosis for knowledge + knossos, for mythical).

“The advantage of doing something for more than ten years is that it brings out who you truly are, whether you want it or not,” Koenig says. “The book is a mishmash of multiple authors: from the carefree, late-20s version of me to the mature, almost-40 version that is accepting of all that’s going on in my head, from the fear of death to awkwardness in relationships.”

Though the words are not all sad, the reader will find “traces of blue” across its pages. Sadness originally meant “fullness”, from the Latin satis, Koenig says. “To be sad meant you were filled to the brim with intense emotion,” he adds. “It was not a malfunction in the joy machine. In fact, there’s always a twinge of sadness in great joy.”

Casting new spells

Why does it matter to have words we have for what we feel?

Partly, the book is an act of rebellion against a language that has been handed down to us with no attempt to encompass our larger, intangible emotions. Working on this project made Koenig acutely aware of how much of language is just a “crude, simplistic and reductive mechanism to make the enormity of reality fit inside our heads”.

He also sees words as constellations that make navigation between emotions, and people, easier. “You can join the dots in different ways to allow for more reflective thinking.”

On a related note, studies have linked emodiversity with positive health outcomes. The more we are in touch with our more-discreet emotions, the easier it becomes for us to adaptively regulate ourselves, found researchers from Cornell University, in a study on emodiversity and biomarkers of inflammation, published in the journal Emotion in 2017.

In terms of emotional diversity, languages such as Hindi, Urdu, Malayalam, Tamil, Kannada, Gujarati, Marathi, Tangkhul Naga and Khasi are among those with a large expressive vocabulary, says Abhishek Avtans, a linguistics professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands. This could be because of their organic emphasis on expressiveness and also due to their long cultural encounters with people speaking Persian, Arabic, Portuguese and English.

This rich expressive vocabulary emanates from culturally specific phenomena, traditions, and environmental conditions. “Khasi has about 20 words describing various types of walking, from ‘walking as if on pins’ (kjik kjik) to walking longingly (hir hir), and it’s because walking has traditionally been a preoccupation, a necessity, an endurance, in their mountainous terrain,” Avtans adds. “Tangkhul Naga has words like yán for a sudden short-lived feeling of happiness or sadness, yín for a sense of emotional disturbance caused by extremely beautiful or extremely unappealing colours.”

There are similar specific expressions in ancient languages with their origins in Africa, Scandinavia, Greece, South-East Asia, Central America. (See Speaking in tongues for more).

“Some languages are rich in emotional vocabulary because they are just more open to soaking up words from multiple linguistic sources. In Hindi, pyar, prem, sneh, are from Sanskrit. Muhabbat, ishq, arzoo (leaning towards desire) are from Arabic in Urdu,” says American translator Daisy Rockwell, whose translation of Geetanjali Shree’s 2018 Hindi novel Tomb of Sand won this year’s International Booker Prize.

Rockwell visualises words as having clouds of meanings hovering around them as they travel between people. “The more a word has been used, the larger its meaning-cloud gets. We create compounds like this all the time in our speech and writing in order to stretch the boundaries of words and language,” she says.

When it comes to English, colonialism could be one reason why the language stayed flat. “The colonisers weren’t concerned about borrowing emotions from the colonised. Their aim was to create an efficient language for ease of business, and this brought limitations. It couldn’t have become one of the most widely spoken languages in the world with 20 different ways to describe the simple act of walking,” says Avtans.

English isn’t as inadequate as we may think, argues author and translator Jerry Pinto. “Every language at any point in its history has been unable to fully convey what its speakers are feeling or saying. Think about the verb ‘love’ in English: I love my mother, I love my country, I love lobster, I love a massage. But I love them all differently. We’re all individuals with different vocabularies responding to the same word differently. It’s how we choose to deploy the available resources to create new imagery that matters,” Pinto says. Because in the end, “language will never evolve ‘fast enough’. All we have are symbols that we’ll keep rearranging to form words.”

SAY WHAT YOU FEEL

Take a look at 15 words created by American writer, graphic designer, video editor and voiceover artist John Koenig, as he sought to put syllables to emotions left undefined by language.

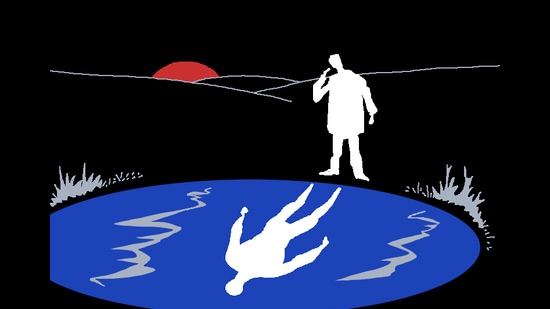

sonder

n. the realisation that each passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own, an epic story that continues invisibly around you like an anthill sprawling deep underground, with elaborate passageways to thousands of other lives in which you might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a lighted window at dusk.

From the French sonder, to plumb the depths. Can be used as noun or verb, as with “wonder”

.

pax latrina

n. the meditative atmosphere of being alone in a bathroom, enjoying a moment backstage from the razzle-dazzle of public life.

From the Latin pax (a period of peace) + latrina (toilet)

.

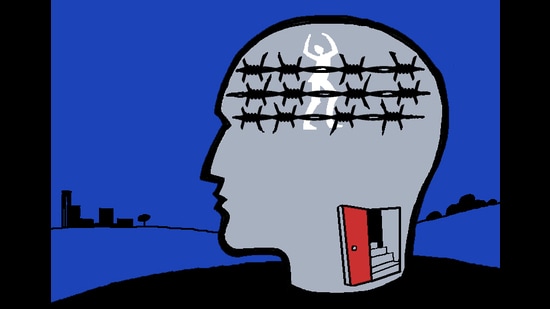

povism

n. the frustration of being stuck inside your head, unable to see your face or read your body language in context, only ever guessing how you might be coming across.

From point of view + ism. Pronounced “poh-viz-uhm”

.

ringlorn

adj. the wish that the modern world felt as epic as the one depicted in old stories and folktales — a place of tragedy, transcendence, oaths, omens and fates — rather than an open-ended parlour game where all the rules are made up and the points don’t matter.

From ring (a key element in many sagas and myths) + -lorn (sorely missing)

.

nyctous

adj. feeling quietly overjoyed to be the only one awake in the middle of the night, taking in the world like an empty theatre between productions.

From Nyctocereus, a genus of cactus that blooms only at night

.

vellichor

n. the strange wistfulness of used bookstores, which seem infused with the passage of time, filled with thousands of old books you’ll never have the chance to read.

From vellum (parchment) + ichor, the fluid that flows in the veins of the gods in Ancient Greek mythology

.

adronitis

n. frustration with how long it takes to get to know someone — spending the first few weeks chatting in their psychological entryway, with each subsequent conversation like entering a different anteroom — wishing you could exchange your deepest secrets first, and ease into casualness over time.

In Ancient Roman architecture, an andronitis is a hallway connecting the front of the house with a complex inner atrium

.

lilo

n. a friendship that can lie dormant for years only to pick right back up as if you’d seen each other last week — all the more remarkable since certain other people can make every lull in a conversation feel like an eternity.

From lifelong + lie low. Pronounced “lahy-loh”

.

kairosclerosis

n. the moment when you look around and realise you’re currently happy, consciously trying to savour the feeling, which prompts the intellect to identify it, pick it apart and put it in context, where it slowly dissolves until it’s little more than an aftertaste.

From the Ancient Greek Kairos (a sublime or opportune moment) + sklerosis (hardening)

.

lisolia

n. the satisfaction of things worn down by time — broken-in baseball mitts, the shiny snout of a lucky bronze pig, or footprints worn through wooden floorboards or stairs.

From the Italian liso (worn down) + oliato (oiled)

.

tirosy

n. a complicated feeling of envy and admiration for people younger than you, which you simultaneously want to preserve forever and gleefully undercut.

From the Latin tiros (beginners, new recruits) + jealousy. Pronounced “teer-uh-see”

.

énouement

n. the bittersweetness of having arrived here in the future, finally learning the answers to how things turned out, but being unable to tell your past self.

From the French énouer, to pluck defective bits from a stretch of cloth + dénouement, the final part of a story, in which all the threads of the plot are drawn together

.

aimonomia

n. the fear that learning the name of something — a bird, a constellation, an attractive stranger — will somehow ruin it, inadvertently transforming a lucky discovery into a conceptual husk.

From the French aimer (to love) + nom (name)

.

chrysalism

n. the amniotic tranquility of being indoors during a thunderstorm.

From the Latin chrysalis (the pupa of a butterfly)

.

nilous

adj. anxious to imagine how many times you have barely avoided catastrophe, which makes it feel like something of a fluke that you have survived this long, leading you to wonder when the string of luck might run out.

From the Old English nigh (almost) + nihil (nothing. Pronounced “nahy-lis”.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here