On the red carpet of the Met Gala in May, celebrities took a loose approach to the Gilded Glamour theme, which referred to the Gilded Age, America’s late 19th-century period of excess. Not Billie Eilish. The American singer, wrapped in an upcycled ivory and pistachio corseted gown, custom-made by Gucci, won comparisons to the 1885 portrait of Madame Paul Poirson by painter John Singer Sargent, who captured many fashion ensembles of the fin-de-siècle era. The dress was on point, but it was Eilish’s vintage choker by jeweller Fred Leighton, a black band with dropping diamonds, that cemented the reference to the Gilded Age.

Chokers were widely popular at the end of the 19th century, when they were used to accessorise the low décolletage typical of the evening dresses of the period. Also known as colliers de chien, or dog collars, popular styles at the time included fabric bands decorated with a central plaque similar to the style worn by Eilish, articulated bands made of gemstones, and necklaces made of rows of pearls encircling the wearer’s neck up to their chin. As the name “choker” suggests, and as anyone who has worn one for more than a couple of hours can attest, this style of necklace isn’t particularly comfortable. Consuelo Vanderbilt, the American socialite who became the Duchess of Marlborough in 1895, owned one made of 19 rows of pearls. In her autobiography, The Glitter and the Gold, she candidly wrote that her dog collar always gave her a “chafed neck”.

Despite the discomfort, chokers have come in and out of style regularly throughout history. The British Museum has an early example from 2600BC, from Ur, in southern Iraq. In his book Jewels of the Pharaohs, Cyril Aldred writes that beaded chokers tied with strings were worn by women during the Old Kingdom, between 2700BC and 2200BC. Neck rings, which the Celts called torcs, have been worn for centuries in African and Asian cultures.

There’s an implicit association between chokers, sexuality and violence. As Marcia Pointon writes in Brilliant Effects: A Cultural History of Gem Stones and Jewellery, “The neck is both a highly vulnerable part of the body and, in women, one of the focal points for beauty and sexual desire . . . that which decoratively encircles it is elided easily into suggestions of strangulation or decapitation . . . the neck-enclosing jewellery that became fashionable in the nineteenth century and was known as a ‘choker’ explicitly alludes to the asphyxiation that its visual form implies.”

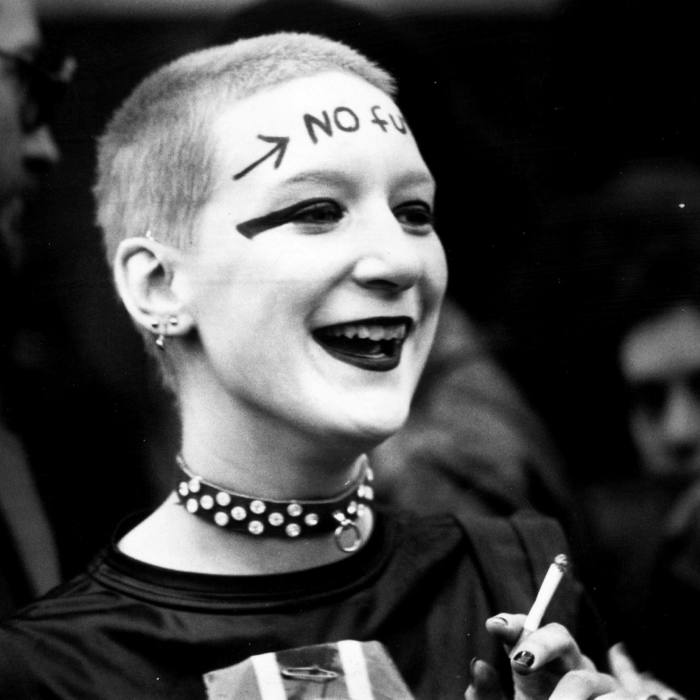

A brief look at history will show that chokers have not always had the most easy of associations. They have been connected to prostitution, famously in Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” painting from 1863, which portrays a naked woman wearing only a thin black string tied around her neck. In the 1970s, chokers became a symbol of rebellion, co-opted by the punk movement, which favoured spiked leather dog collars, sometimes completed with leashes and S&M references. During the 17th century, mourning and sentimental jewels were worn at the neck in the style of a choker, often decorated with ribbon sliders as memento mori, a custom that has tinged chokers with morbidity. Mourning jewellery, often including hair, was then revived in the Victorian era. “There are many examples of human hair woven chokers, which ladies would tie around their neck,” says jewellery historian Hayden Peters, founder of online platform, The Art of Mourning.

Death and decapitation feel uneasily close to mind when looking at a portrait of Anne Boleyn, painted by an unknown artist in the 16th century, wearing a strikingly modern pearl choker adorned with a dangling letter “B”. The necklace, however, could have been the result of a loving gesture by King Henry VIII. According to A History of Jewellery by Joan Evans, the king was fond of the use of initials in jewellery and owned a carcanet, as chokers were known in the Renaissance, with the initials H and K, for himself and first wife Katherine of Aragón. Carcanets were also donned by two other of Henry VIII’s wives, Jane Seymour and Anne of Cleves, as well as his daughter Mary I, and were common throughout the Tudor period.

Unsurprisingly, for much of history, chokers have risen to popularity in conjunction with changes in dressing that put women’s décolletés on display, which adds to the erotic association of the ornament. This was most evident in the 18th century, when women’s fashion in Europe was dominated by low-cut corsets a-la Marie Antoinette. As many portraits show, the French queen wore numerous popular styles including ruffled ribbons, bands knotted with voluminous bows under the chin, single strings of pearls and openwork bands with a central dangling pendant. The openwork bands could also be worn en esclavage, with other dangling elements, such as festoons of pearls and pendants, attached to the choker encircling the neck.

The association between chokers and royalty is a lasting one. “Much of the popularity of the choker has to do with the fact that so many members of British royalty embraced it,” says curator and archivist Annamarie Sandecki. It was Alexandra, Princess of Wales and later Queen consort of the United Kingdom, who popularised the choker in the 19th century. It is said that she favoured the style because it covered a scar that she had around her neck and she was portrayed wearing all kinds of chokers, from simple black ribbons adorned with a single pendant or brooch, in the modest Victorian style, to rich diamond bands and pearl row chokers. Queen Mary, who succeeded Queen Alexandra, was a passionate wearer of chokers, often pairing them with other necklaces, as the early 20th century mode dictated.

Lady Diana Spencer, like Alexandra almost a century before, induced a choker frenzy in the 1980s. “Uptown, women are circling their throats with four to eight strands of pearls, with jewelled brooches as centrepieces. Even turn-of-the-century velvet ribbons with jewels pinned at their centres, once worn only by dowagers, have reappeared,” wrote The New York Times in 1983. “The present trend seems to have started when the Princess of Wales wore a pearl choker as she left for her honeymoon in July 1981.”

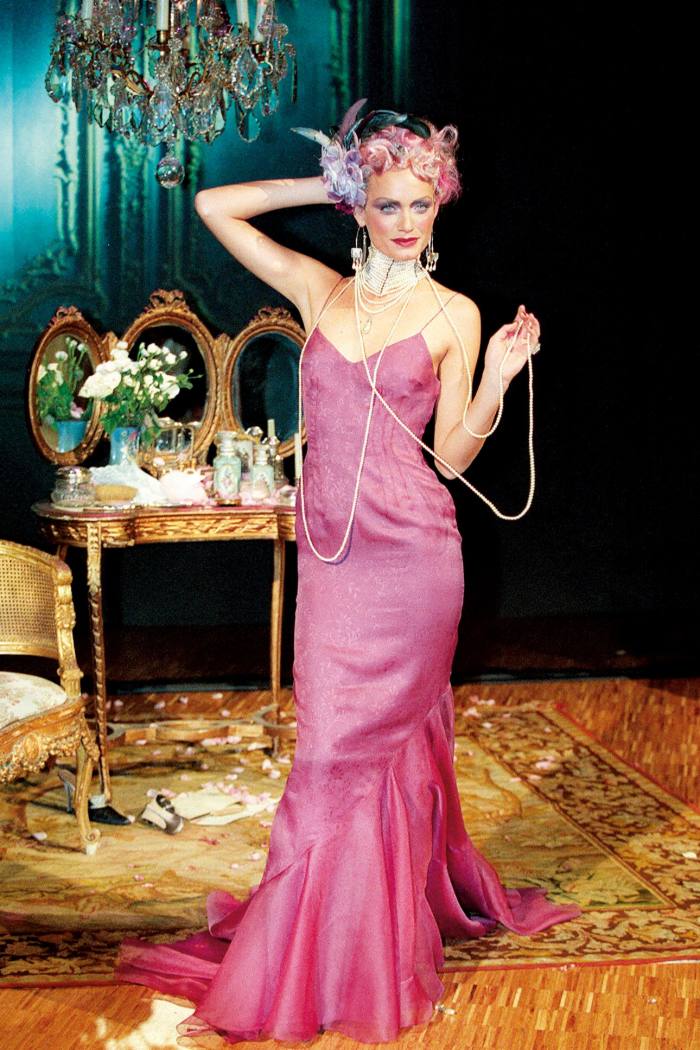

“The choker is associated with everything from power and violence to femininity and wealth,” says vintage jeweller Susan Caplan, an enthusiastic wearer of chokers. Her store sees a steady flow of choker sales, which can peak by 30 per cent when the style appears on the catwalks. Many fashion designers have used chokers in their collections, including Chanel and John Galliano for Dior in the 1990s and Vivienne Westwood, who most famously modernised, radicalised and eroticised the 18th-century saccharine pairing of corset and choker in her 1990 spring/summer “Portrait” collection. For Gucci’s latest cruise collection, showcased in May in Italy’s Puglia, models wore pearl chokers that wouldn’t have been out of place on the Duchess of Marlborough, as well as spiked collars reminiscent of the punk period.

It might be this constant tension between high and low, tradition and subversion, protection (of the neck) and exposure (of the décolleté) that has made chokers one of the most captivating styles of jewellery in history, allowing for its continuous reinvention. Clasped around the neck they can impart the pleasant thrill of defiance and rebellion, and the weight of history.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Fashion News Click Here