“I feel like social media doesn’t allow people from marginalised communities to use it just for fun. All the hate propagated through social media forces us to share or do certain things and we are never able to use the platform for fun,” says Divya Kandukuri, writer, anti-caste activist and co-founder of The Blue Dawn, a mental health support group for people from marginalised communities. “Though it may seem trivial, there is this constant pressure to be active and put our point across. Online and offline activism go hand in hand, and I feel the lines get blurred sometimes.”

Activism ‘burnout’ is real. Constant engagement with social and political issues, particularly on social media platforms that are known to be fickle, brings in multiple vexing challenges. ‘Troll’ culture, hate speech in terms of triggering comments, obnoxious direct messages, hashtags meant to demean a community and indirect attacks in the form of censorship are only a few. All of these impact the mental wellbeing of young activists who are at the receiving end and often find it hard to switch off.

Being vocal about opinions and political agendas often makes a person vulnerable to personal attacks, threats, slut shaming, body-shaming, casteism, colorism and other forms of discrimination, according to psychotherapist Mitali Barot. This can instill feelings of fear, anger, shame, sadness, guilt, isolation and fatigue, which if not addressed outside the virtual universe can begin to cause serious exhaustion.

With the state’s involvement, the imbalance is always there on social media. I always think twice about how I am going to put out a message in a way that it won’t be taken down or it won’t get mass reported.

Yet, social media are necessary as thriving spaces for important discussions. It is where activists, civil society workers, artists and journalists, among others, actively engage with the online community about the rights or welfare of the Dalit, Bahujan, LGBTQIA+ and minority communities and climate emergencies. They highlight the role of social media in providing many interesting ways to educate and initiate difficult conversations, which may translate into positive or negative real life consequences. Social media has also been an important space of activism for people with disabilities, who might not be able to always participate in offline activities.

As Devika Shetty, a mental health activist based in Goa, explains, “Instagram is a great community for people with ADHD and other psychosocial disabilities. People are able to interact, curate and learn from this space without getting triggered. While in offline spaces, we have to deal with psychiatrists and other people, social media can be affirming and liberating.”

While online assertion becomes an inseparable part of activism in current times, Kandukuri adds, “We should also keep in mind the gap that exists in accessing online platforms, and who gets to convey through these platforms..” .

Pressures experienced on social media

Though considered to be a democratic space, activists have noticed selective censorship of their content on Instagram or Twitter, while hate speech thrived on these platforms. A shadow ban on activists’ posts and notices from the police to delete something from their timeline, which may lead to legal consequences, are also among the factors that add to physical and mental exhaustion for many. The censorship on content is also defined by police forces of the state and big tech corporations that regulate content on social media, which are not caste-sensitive and do not cater to nuanced local issues.

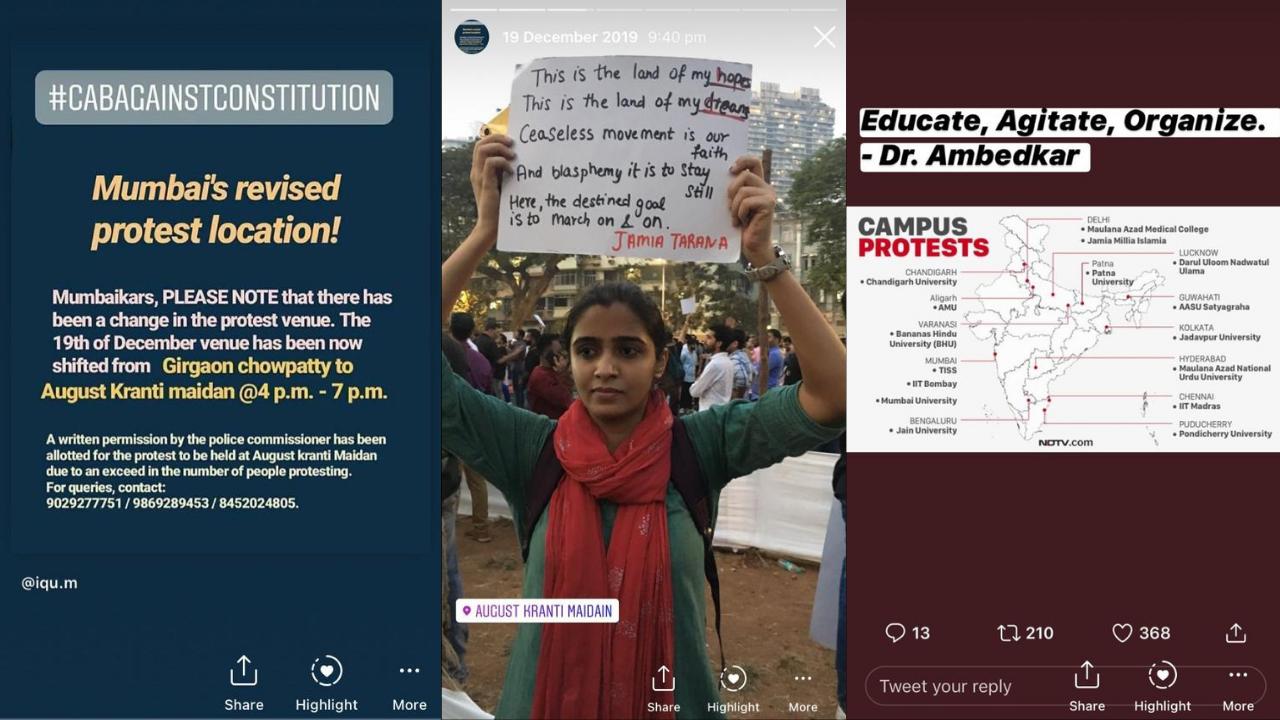

“With the state’s involvement, the imbalance is always there on social media. I always think twice about how I am going to put out a message in a way that it won’t be taken down or it won’t get mass reported,” says Kandukuri, whose friends had received notices from the authorities during the anti-CAA NRC protests.

Here is a little something about my feminist icons today and everyday! #IWD2019

1. Phoolan Devi

A Bahujan woman who was failed buy due process, and who never gave up. Rajput men locked her up and raped her for several weeks, she escaped, came back and killed all of them +— Divya Kandukuri దివ్య కందుకూరి (@anticastecat) March 8, 2019

“This also affects some of the real-life work opportunities, especially for those who come from fields of journalism and communication. Some organisations are not okay with you being so active on Twitter or Instagram with these opinions. This is also an indirect pressure,” adds Kandukuri.

Uttar Pradesh-based advocate and anti-caste activist Harsh Singh, who actively engages on Twitter, narrates a similar incident where he was targeted by users for sharing a case of a Dalit family, who were forced to drink pesticides after government officials destroyed their crops without notice. As the news was not covered by mainstream channels, Singh was targeted by people, who immediately dismissed it as fake news and demanded that a complaint against Singh. Later, when the same news was shared by opposition leaders and some actors, the family got their dues from the government.

Singh also adds that he is tagged and questioned by many to speak on every caste-related issue. While Kandukuri has faced it too in terms of direct messages, she has successfully managed not to engage with them. Expectations or unreasonable demands from followers or non-followers to speak up on every issue or share certain posts is another form of pressure indicating the bleak gap between a personal and public profile.

Battling online hate and impact on mental health

“Many people from the Dalit community, especially women, face extremely hate-filled, casteist, sexist remarks whenever we speak about our cause and present facts. I get immense support mainly from my Dalit, Adivasi and minority friends. It is important to note that the support from other communities is always less as compared to the hate campaign,” says Singh.

According to a 2019 report by Equality Labs, casteist and gender/sexuality-related abuse accounted for 13 percent each of all hate speech on Facebook. A qualitative analysis of such content by International Dalit Solidarity Network found that internet has further exposed women from marginalised and minority communities to a vast number of abusers and bullies, who create an atmosphere of fear further causing severe distress to a number of activists, artists and journalists.

Whenever I feel emotional burnout while sharing and speaking about Dalit issues on social media, I read more about Babasaheb Ambedkar, Jyotiba Phule and Manyavar Kanshiram and their activism and journey. This not only gives me hope but guidance to move towards their path.

Additionally, instant responses and impulsive opinions on social media leave no space for a healthy discussion and nuanced dialogue. These combined factors affected Kandukuri’s mental health in multiple ways which convinced her to take regular breaks from Instagram at times when she hit the saturation point.

“The targeted harassment and abuse that comes from anyone and not just the right wing or just the people who are not anti-caste has been normalised to an extent that I myself have accepted it in my head that this is inevitable,” she adds.

According to Singh’s observations, the discussion on social media becomes personal from the day you begin speaking about your community and the intersectional social, political matters of concern. He points to the several atrocities, stories and visuals that are shared on social media on a daily basis, but are never picked by mainstream media journalists. Though triggering and tremendously disturbing, Singh says it is not possible to ignore them.

Here’s an example of online hate speech that Harsh was subjected to:

Oh you definitely look like you are starving. https://t.co/6YVBJqIMyu

— Mona Ambegaonkar (@MonaAmbegaonkar) March 10, 2022

Shetty, who actively speaks about unrest in Kashmir and against casteism, highlights the emotional burden and self-introspection mainly caused by unexpected responses from acquaintances and people in similar networks on the internet. This brings in an additional layer of anxiety, triggering a series of questions like, “Were my expectations of this person wrong?” or “Did I create a safe space for them before?” and “Am I reading them wrong?”. It may also mean losing friends and dear ones, which she says is inevitable on social media and eventually people get used to it.

In order to identify the signs of burnout or exhaustion, Barot says one must keep a check on minor changes in patterns of thoughts, emotions, mood, sleep and eating habits, and the manner in which engagement with family, friends and peers is happening on a daily basis.

“If there are changes, which are persisting or recurrent, consider this as a message from your body and mind that an underlying issue needs to be addressed and investigated. To begin with, do it through introspection and then share it in a safe space with someone you trust can hold your vulnerability responsibly. If it persists, take help from a professional,” she explains.

‘We go back and read our anti-caste leaders’

As Barot suggests, social media detoxing, reporting and blocking accounts that propagate hate are one of the primary ways to shun the noise and even call out the perpetrators. However, Kandukuri, who had taken periodic breaks from Instagram in 2020 and 2021, notes that it is not always the most viable option for individuals coming from marginalised backgrounds, for whom there is little difference between the hate and isolation experienced inside and outside the virtual world. As she puts it, “I would not say I experience emotional burnout or fatigue, because I believe that our births are political. You feel like taking a break but you cannot.”

Meanwhile, Shetty strongly believes in censoring social media when needed and has relatively managed to dissociate her online and offline activities. On occasions of emotional burnout, Shetty says communicating about it to people who are accessible and close is one of the resorts. “I feel burnout at a very high level and over the years, I have figured out ways of self-care. I access therapy, medications and have created a safe cocoon where people are willing to listen to me. Most of the time, I sleep through it,” she adds.

In addition to finding solace among trusted human companions, taking refuge in the safe space offered by writings of anti-caste leaders is one of the most important ways for Kandukuri and Singh to seek hope, learn and to conserve energy.

“The method that I employ is that I always, always go back and read things that are written by black feminists and our own leaders such as translated versions of poems by Savitribai Phule. I go back to see what they did during their times when they dealt with colonialism and casteism and there was no internet to communicate. That’s the only way to keep up,” says Kandukuri.

“Whenever I feel emotional burnout by sharing and speaking about Dalit issues on social media, I read more about Babasaheb Ambedkar, Jyotiba Phule and Manyavar Kanshiram and their activism and journey. This not only gives me hope but guidance to move towards their path,” Singh shares.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here