NASA’s Orion capsule has survived the hottest and fastest reentry ever performed by a spacecraft by intentionally skipping off the atmosphere before splashing down off the coast of Baja California, Mexico.

The uncrewed capsule, which launched Nov. 16 atop the 30-story Space Launch System “mega moon rocket” as part of NASA’s $20 billion Artemis 1 mission, made its triumphant return from its 26-day, record-breaking, 1.4 million-mile (2.2 million kilometers) round trip to the moon at 12:40 p.m. EST this afternoon (Dec. 11). The “textbook entry” of the spacecraft, which can hold six crewmembers, is the climactic finale of a nearly flawless test mission. The next time the rocket flies, it will be with humans on board.

To cap off its journey, Orion made a “hellish entry”, returning hotter and faster than any space vehicle ever has. Temperatures at its heatshield soared up to 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (around 2,800 degrees Celsius) as it entered Earth’s atmosphere at roughly 25,000 mph (40,000 km/h), or 32 times the speed of sound, according to NASA.

Related: To the moon! NASA launches Artemis 1, the most powerful rocket ever built

“[Orion] still has all that energy that the launch rocket first put into it. All that energy— enough to power 4,000 to 5,000 homes in a day — we have to get rid of.” John Kowal, Orion’s thermal protection system manager, said during a NASA livestream just before the landing. “The vehicle comes slamming into the atmosphere and starts trying to push the air out of the way. That air is pushing back, the pressures go up, the temperatures go up — we’re talking upwards of around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit [5538 degrees Celsius] in the flow field [the air around Orion]. The flow field wants to give that energy back, so that’s what the heat shield is going to see.”

To make it back safely, the capsule intentionally skipped off the atmosphere like a stone across a pond surface, eventually slowing to just 20 mph (32 km/h) with the added help of its heat shield and 11 parachutes. After plopping down safely into the ocean, Orion was hauled aboard the USS Portland, a U.S. Navy ship.

The Artemis 1 flight was the first of three missions designed as vital test beds for the hardware, software and ground systems intended to one day establish a base on the moon and transport the first humans to Mars. This first test flight will be followed by Artemis 2 and Artemis 3 in 2024 and 2025/2026, respectively. Artemis 2 will make the same journey as Artemis 1 but with a four-person human crew, and Artemis 3 will send the first woman and the first person of color to land on the moon’s surface, at the lunar south pole.

Following its launch, the Artemis 1 rocket accelerated the Orion capsule to 22,600 mph (36,371 km/h), sending it to orbit the moon in just six days. On Nov. 25, the capsule fired its engines to enter a high-altitude lunar orbit, setting a record for the farthest a spacecraft designed to carry humans has ever traveled from Earth — 270,000 miles (430,000 km). Four days later, the craft performed another burn to slingshot around the moon and set out on a return path to our planet.

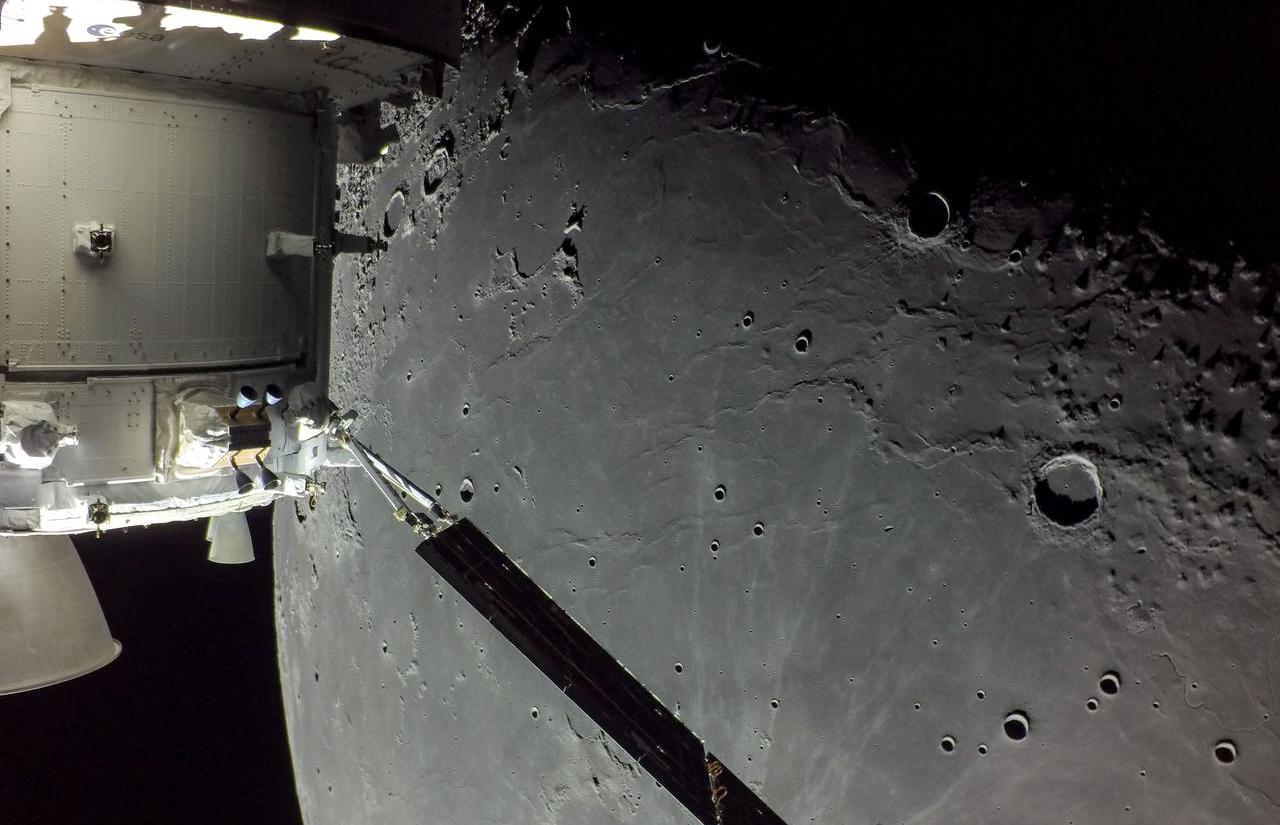

Despite months of delays and three scrubbed launch attempts (the first two due to technical faults, the third because the gigantic Space Launch System was packed away to survive Hurricane Ian), Orion’s performance has delighted NASA mission controllers. The European Space Agency service module that propelled Orion during its journey produced much more power while also using less fuel than had been expected, according to NASA, and the craft has followed its planned course closely while snapping some stunning images of Earth and the moon. Stowed aboard Orion is a manikin that NASA will now test for exposure to space radiation.

To return intact from the moon, all spacecraft have to hit a small target in Earth’s atmosphere a little more than a dozen miles wide at just the right angle. Too sharp, and the craft is incinerated; too shallow, and it bounces off the atmosphere and back into space.

Orion’s flight engineers rotated the capsule during its descent to deliberately pull off an atmospheric bounce — a feat that reduced the g-force experienced on board from 6.8 to 4, cooled the craft’s heat shield and increased the target window for reentry. NASA flight engineers considered performing skip reentries during the Apollo program, but the lack of advanced computer modeling or an onboard guidance computer made the tricky maneuver too risky.

“It’s historic because we are now going back into space, into deep space, with a new generation.” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said. “This is the program of going back to the moon to learn, to live, to invent, to create in order to explore beyond.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest For Top Stories News Click Here