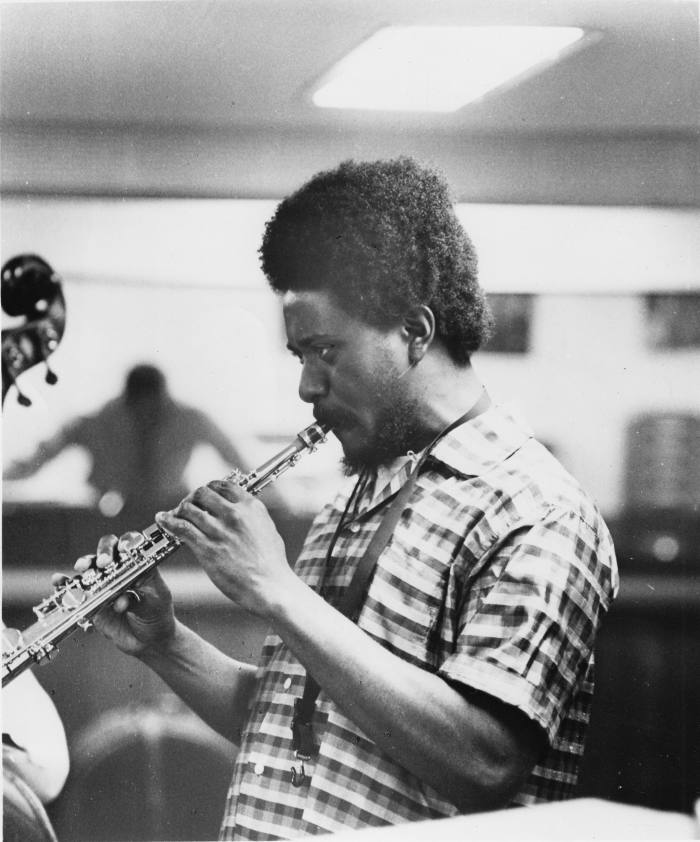

“The whole musical persona of Pharoah Sanders,” wrote the African-American poet and critic Amiri Baraka, “is of a consciousness in conscious search of a higher consciousness.”

Sanders himself put it slightly differently in an interview in 2016. “Whatever comes through me,” he said, “I’m trying to express and free myself, and let it out, whatever it is.”

Such searching sometimes took Sanders, who has died at the age of 81, to the outer limits of harmony and form. This was often to the consternation of a critical establishment that, in the early part of his career at least, disparaged his tone on the tenor saxophone as “primitive”, “nerve-racking”, even akin to “elephant shrieks” that “appeared to have little in common with music”.

He established his reputation (with his peers, if not with the critics) in the mid-1960s as a leading figure in so-called free jazz, the harmonic revolution in improvised music first fomented by Ornette Coleman in a series of incendiary recordings released between 1959 and 1961.

That was the year a penniless Sanders first pitched up in New York City, ready to join the wave that Coleman had set off. As his contemporary Albert Ayler described the “new music” scene in the Big Apple during that period: “[John Coltrane] was the Father, Pharoah was the Son, I am the Holy Ghost.”

Farrell Sanders was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the American South, in October 1940. (The sobriquet Pharoah was bestowed on him in his early twenties by the visionary bandleader Sun Ra.) His mother worked in a school cafeteria and his father was employed by the local municipality.

It was a musical family. Sanders took piano lessons from his grandfather and was soon playing clarinet in the high school band, having also tried his hand at the drums. He paid $17 for his first clarinet, after seeing an advertisement posted in church. But it was the saxophone that really cast a spell on him.

“In high school I was always trying to figure out what I wanted to do as a career,” he said. “What I really wanted to do was play the saxophone.” Sanders did so eventually, starting on the alto before moving to the tenor, which “was the most popular instrument at that time to get work”.

Sanders would rent the school saxophone and make money playing rhythm and blues gigs in and around Little Rock, sitting in with visiting artists such as Bobby “Blue” Bland. The legacy of Jim Crow still cast a shadow over Arkansas in the late 1950s, however, and the working conditions for black musicians in the South were difficult. “You had to play behind the curtain,” Sanders remembered. “They didn’t want to see black people.”

In 1959, he moved to California, where he took up a scholarship at Oakland Junior College. He studied art and music there, while also working as a jobbing musician around the San Francisco Bay Area, where he was known as “Little Rock”. Two years later, he headed east.

Sanders’ early days in New York were hard. He was often homeless and frequently destitute. He would give blood, for $5 a pop, and subsist on cheap slices of pizza. His saviours were two giants of jazz: Sun Ra and Coltrane.

Sanders had a job in a club called the Playhouse in Greenwich Village, which enabled him to listen to the Sun Ra Arkestra, who had a residency there. When the Arkestra’s tenor player, John Gilmore, left to tour Europe with the legendary drummer Art Blakey, Sanders stepped into the breach. And then, in 1965, Coltrane invited him to join his band, as he began to push his sonic explorations even further into the musical stratosphere.

The combination was explosive — and is preserved on recordings such as Ascension and Meditations.

Coltrane arranged a deal for Sanders with the Impulse! label, and in 1967 he recorded his first album for the imprint, Tauhid. A string of recordings followed, perhaps most notable among them Karma — now a staple of the “spiritual jazz” canon — which showed off Sanders’ lyricism, as well his harshly exploratory side. After Coltrane’s death in 1967, Sanders worked with his wife, Alice, and, in 1988, won a Grammy for his contribution to Blues for Coltrane, a tribute to his mentor.

Sanders recorded and gigged steadily through the last three decades of his life. His last album Promises, a collaboration with the producer Floating Points and the London Symphony Orchestra, was released in 2021. The Financial Times called it “immersive and richly detailed”, the “sound of a promise fulfilled”.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here