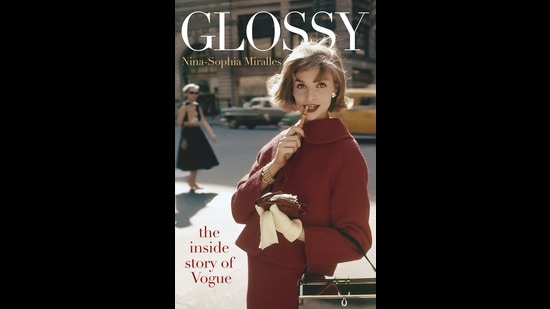

The history of Vogue is richer than you think, says Nina-Sophia Miralles, author of Glossy: The Inside Story of Vogue (2021). “It is arguably the most famous magazine that has ever existed… I knew the story of how they got there, and how they stayed there, had to be really intriguing… and it was.”

Miralles’s book is an account of the magazine’s 129-year history before and beyond Anna Wintour, the woman who has been synonymous with the masthead in her 34 years (and counting) as editor-in-chief.

In Glossy, then, are tales of unimaginable feats such as working through the London Blitz of World War 2, inventing the catwalk amid World War 1, and protecting Vogue printing presses in Paris from being used by the Nazis.

“Vogue magazine started, like so many great things do, in the spare room of someone’s house,” Miralles says in the book. Its founder, high society New York lawyer Arthur Turnure, graduated from Princeton but practised law rather half-heartedly. His true passion was publishing. So he served for a while as art director of Harper & Brothers (now HarperCollins) before branching out on his own to launch this lavishly illustrated magazine. “The definite object is the establishment of a dignified authentic journal of society, fashion and the ceremonial side of life,” he said, in his opening letter to readers, in the first edition of Vogue, in 1892.

Finding out about the early years took some true detective work, Miralles says. She sought out old letters and diaries, tracked down sources to interview, and dug through archives. Even the latter parts of the 20th century weren’t easy; the best stories were only shared anonymously, and many had to be left out because there was no way to verify them.

Here’s a look at the history of the magazine through five revelations from the book.

Inventing the catwalk during World War 1

In 1909, three years after Turnure died from pneumonia, aged 50, Condé Montrose Nast (the founder of today’s magazine group) acquired Vogue and began to transform it, giving it a global presence.

As part of this effort, he appointed ambitious Vogue up-and-comer Edna Woolman Chase editor-in-chief (she would remain in that position for 38 years, still a record at Vogue).

Under Chase, Vogue flourished. But she was, by all accounts, the original devil in Prada. She made it mandatory for all women employees to wear black silk stockings, white gloves and white caps while in the office. She scoffed at employees in distress, wrote hateful letters to those who quit, and blackballed those who tried to move to rival magazines (so successfully that some ended up impoverished, and she still wouldn’t work with them).

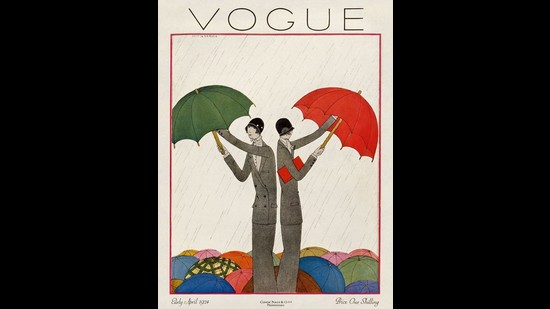

Amid it all, Chase also invented the catwalk. As the Great War of 1914 disrupted supply chains between France and the US, Chase commissioned a few New York designers to produce unique collections, which she then displayed to society ladies on models she had trained in the art of the strut. The event was pegged as a charity fundraiser for WW1. No one expected it to do very well. “She had a really hard time persuading people to come on board,” Miralles told Wknd. “No one could see the appeal of watching women walk whilst wearing clothes.”

A gay editor, for a brief while, in the 1920s

When Dorothy Todd was editor of British Vogue from 1922 to ’26, she turned Vogue into a cultural klaxon. Women need to be taught how to think as well as how to dress, she said. Her version of Vogue was cleverer, more eclectic and more literary. But her stint was brief; she was sacked after she moved in with her female secretary. Officially, she was fired for turning the fashion magazine into a place of avant-garde poetry and “unusual” celebrities, a shift that was said to have caused immense losses to the magazine.

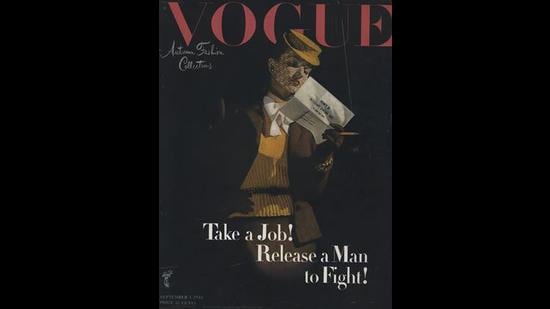

Underground photo shoots in WW2

Everyone who worked at British Vogue during World War 2 kept a suitcase beside their desks, not for spare clothes or toiletries, but so they could rush out with their stacks of pages and layouts and copy, if an air raid siren went off. They continued to work during air raids, sheltered in the basement six floors down. Fashion shoots took place underground too. It was too unstable and unsafe to shoot above ground.

It was an unusual set of editions that hit the stands here during this time. By 1942, a cartoon soldier named General Economy was wearing fabric ends and a folded-newspaper cap to underline the need for thrift. He also advised readers to save “every page of every paper for re-pulping… every scrap of mending thread.” A 1943 cover advertised coupons alongside style advice.

Saving the Vogue presses from the Nazis

Meanwhile, the staff of Vogue Paris went to extraordinary lengths to keep the magazine’s printing presses from being used by the Nazis. Editor Michel de Brunhoff went so far as to hide equipment behind a false wall, Miralles says. “In one particularly tense interrogation, a German officer kept leaning against it while questioning the staff. Luckily, they were not discovered. But they risked their lives.”

A $1 million photoshoot

Diana Vreeland, editor-in-chief of Vogue US from 1963 to 1971, famously called the bikini “the most significant thing since the atom bomb”. Vreeland was also in charge of the magazine’s most expensive photoshoot ever. It cost more than $1 million then, and lasted five weeks in Japan.

The 26-page special was titled The Great Fur Caravan and featured, among others, a 7-ft-something sumo wrestler and German supermodel Veruschka von Lehndorff. It told the whimsical story of a young woman on a first-class train journey around the Japanese Alps, exploring the snowy mountains in her “fabulous” furs, and eventually falling in love with the gentle Japanese giant.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here