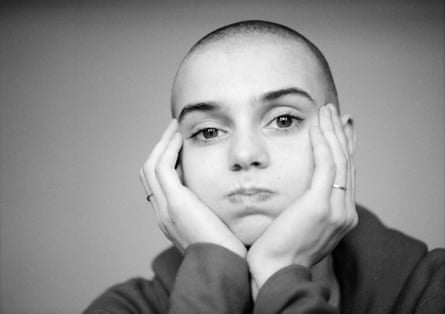

‘She was very beautiful and very wild’

Anne Enright, author

Sinéad O’Connor was a daughter, a mother and a sister, she made a family that brought many people into its extended web of care, one that included the fathers of her four adored children. So when the world mourns an iconic talent and a great star, people in Dublin think about those caught up in her astonishing life story who are now bereaved. All these people joined in the battle for Sinéad’s mental health and worked for the protection and wellbeing of her children, and all of them, including Sinéad, contended with the distorting power that fame brought to her life. It was not easy. Somewhere in there, beyond the huge talent and huge difficulty, beyond public adoration and vilification, the ardent and anguished connection she felt with her fans, was the hope that her great heart and searching wit would bring her through. She was very beautiful and very wild, and she trembled with the truths she had to tell. Sinéad’s grief at the loss of her son was hard to witness and her loss will spark difficulties in many people. Before we turn her into a rock’n’roll saint and lift her image even further from the real, let’s check in with each other and lift the sadness where we can. It’s what she would have wanted. There was none like her. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a h-anam dílis (May her faithful soul be at the right hand of God).

‘The greatest trauma was always her own’

Neil Jordan, film director

I was walking with my granddaughter towards Dalkey, and played her a track Sinéad had just sent me, called No Veteran Dies Alone [from a planned new album of the same name]. It was one of the most extraordinary uses of her searing voice and her blazing lyrical talent. I told Sinéad when she first played it that if she wanted to make a video, I would be immediately available. The song was, or seemed to be, about how any cry of pain, for help, for understanding, can be so easily misinterpreted. She told me record companies wouldn’t be interested in funding a video for her, which I found odd, sad, or maybe just reflected how out of date I was. Anyway, the sound was echoing from my phone, and I turned a corner and there she was, sitting in the garden of the small pink bungalow she had rented. Head covered in an untidy headscarf, sitting on a bench in her nightgown. Of course, she was a Muslim now. Smoking away, drinking a coffee. It was beautiful to sit there for a while, while tourists ambled by, none of them having any idea who she was.

She seemed happy, at last. I had known her on and off since the 80s, relished a friendship with her that thankfully never went offside. She was always devastatingly beautiful and terrifyingly provocative, a combination that some found hard to deal with. When I had to cast an actor for the Virgin Mary in my film The Butcher Boy I thought first of dragging Marilyn Monroe somehow back from the dead – a young kid in the Irish 50s could easily have confused those icons – and then had the much more interesting idea of asking Sinéad to play the role. She said yes immediately, having recently been ordained as some version of a Catholic priest and played the role in the Blessed Virgin Mary gown with a beautiful, mesmeric simplicity. Her face immediately fell into that statuesque grace any Irish child would have remembered, framed by the veil of Prussian blue. “Ah Francie, for fuck’s sake …”

I was godfather to her youngest son, Yeshua, and did my best, as did Yeshua’s father Frank, to help with the troubles of his older brother Shane. His tragic death 18 months ago would have put a splinter of ice in anybody’s heart, let alone a mother’s. Sinéad had kept in touch, through spells in hospitals and work with trauma victims in Detroit, but the greatest trauma was always her own. And now she had survived, had a little pink cottage and a bench and was still making extraordinary music out of her extraordinary troubles. She played me the latest mix of the song, and it went straight to the heart again with that voice that sounded straight out of a convent school in Dublin and kept on reverberating, dragging decades of pain with it. The first line: “There is one me, that nobody sees …”

She left that house and moved to Brixton. Sent me several emails, saying how glad she was to be out of “Direland”. She could always turn on a dime. Anyone who wants to understand her, and I’m sure that will now include most of the planet, should listen to [the currently unreleased] No Veteran Dies Alone. And I can only hope she was right.

‘She lived her truth’

Róisín Murphy, musician and fan

The world had never seen anything like her. I remember my first sight of her on late-night television singing Troy and she kicked the screen out of the TV, metaphorically. I was mesmerised – and proud she was Irish. She was brilliant – literally brilliant – shining. She lived her truth, always so unbelievably brave. We’ve lost another precious thing which is always hard to process, but Sinéad’s legacy of all that is beautiful and harrowing in truth will continue to show us the light.

‘She loved my explicit lyrics’

MC Lyte, rapper who collaborated with O’Connor on the remix of I Want Your Hands on Me

I first met Sinéad in this swanky little lounge area of a New York City hotel with Fachtna [Ó Ceallaigh, O’Connor’s manager from 1986-90], who was friends with my manager. They had reached out because they wanted me to appear on the I Want Your Hands on Me remix. I believe the photo on the cover is actually from the day we met. I remember asking: “Why do you want me?” It turned out it was because of some explicit lyrics that I said in a song, mainly the lyric: “Shut the fuck up.” She was so intrigued by this young person using this language to get her point across and she wanted me to say the words exactly like that on the remix.

Sinéad was really soft spoken, but she had a clear vision of what she wanted to put out into the world. She was really honest and kind – sometimes it’s hard to be those things at the same time, but she was able to do it. She asked a few rap artists to support her when she performed live. I think she appreciated the genre for its honesty, and for the ability of those in it to speak a language that was not accepted by the mainstream. We didn’t care! I think that she was very much like that, too. Had it been a different time, and if she didn’t sing as well as she did, she might have rapped to get her message across. She wanted to speak about what went on inside of her, she wanted to be honest even when lots of folks didn’t agree with it. At least you can rest easy knowing you’ve said what needed to be said.

I remember a time where she came on the road with us. We pulled over at a gas station and we broke out into this game of “it” – some people call it “coco-levio”. She was so tickled by the whole thing, she was having so much fun running around and playing this very simple game. I was probably only 17 or 18 then, but as I got older, whenever I thought of that moment, it reminded me to absorb the simple times. Even when we’re wrapped up in everything that is happening in the world, something as simple as coco-levio can relieve all the stress. It made her so happy.

For those who know her, moments like [O’Connor tearing up a photo of the pope] isn’t her whole story. But it’s not very different from what the Dixie Chicks said about George Bush – it really takes people being gutsy and courageous to say the things that other people won’t. Before you know it, the truth is out and everybody realises: “Oh, wow, there was some truth to that.”

I feel an overwhelming sadness now she’s gone. Fifty-six is so young considering we’ve got so many ways to stay alive. What a powerful force of nature she was. And is. What do you do with that type of energy? She lives on.

‘The power of her voice broke the mic’

Jah Wobble, musician, collaborated with O’Connor on 1991’s Visions of You

Sinéad was a very special singer and person. I have a vivid memory of her at the time of recording Visions of You breaking the membrane in an expensive microphone. I took the track home to Dellow House with me and got cracking on the lyrics. I lay on my bed and wrote them. I swear I could hear the song clearly with Sinéad singing in my head even before we recorded it. The sheer power of her voice, her “chi” as the Chinese would say, did for the mic.

She was a Celtic female warrior. She had a great, mischievous sense of humour and unlike many big stars didn’t take herself too seriously. She had a temper, too. And she was very brave. Not afraid to be outspoken, if she felt the need. A good heart, she had. An Irish heart.

‘She defied a TV network, a country, a religion’

Carrie Brownstein, Sleater-Kinney guitarist and fan

In 11th grade, my group of friends had a sleepover the night before Sinéad O’Connor tickets were going on sale. She was coming through Seattle on her I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got tour. We spent the night listening to O’Connor’s records and taking turns shaving each other’s heads. We were still in high school, so our version of near-baldness was less rebellious than the full dome – we opted instead for undercuts, buzzing only the back of our heads. I suppose even then, I knew I’d never be as brave as Sinéad O’Connor, I would never defy a TV network, a country, a religion. Her boldness was not merely performative, nor was it costume or cultural currency. Most of us couldn’t sacrifice like she did, at the expense of careers and livelihoods, our own hearts. O’Connor had guts and grit and a voice rooted in a deep ache, her singing winged and weighted, a bird clutching a stone. Fierce fragility. No one sounded like Sinéad O’Connor – and no one ever will.

‘I love red hot people, and she was fire’

Simon Napier-Bell, O’Connor’s manager, 2014-2015

She put a thing on Facebook saying she was looking for a new manager – I thought it was a joke, to be rude to her old manager. But she was serious, and there was no one I’d rather manage. The history of pop is not great music, only – it’s great imagery, which isn’t enough either. So when those two things dovetail, you become a huge artist. In my mind, there were two things with Sinéad – one, the incredible first hit record, and then the extraordinary thing that happened on Saturday Night Live when she tore up the picture of the pope. To me, that’s when she became a superstar; that was the most wonderful thing I’d ever seen.

I love red hot people, and she was fire – I love playing with fire. One of the problems with management is you take a new artist, you make them a huge success, and it gets very boring. Now they’re playing gigs and making lots of money; you make a million a year but it’s not as fun as when you were breaking them. I felt she was an artist where that excitement would continue – she felt like an artist who meant something.

There was a wonderful occasion when we went to Las Vegas, and she sang at a Conor McGregor fight. She was passionately Irish. Her music was guided towards redeeming the wrongs that Ireland had suffered; she equated the wrongs she suffered as an abused child with the wrongs that Ireland had suffered. And here were 20,000 Irish people at the MGM Grand, and probably a couple of hundred Americans. There were 24 flights from Ireland in the previous two days and every single one ran out of beer halfway across the Atlantic, and that continued in the MGM Grand. The cheer when she stood up on the podium was so vast that she couldn’t hear the backing track. But her voice rose above everything else – she had this unbelievable voice that could pierce anything, either with pain or love. And then McGregor won his fight.

She could be sitting with you in the most gentle, nice way, having afternoon tea, and someone could say something and she would go into a fury. And you’d have no idea why. You’d think she’d never come back from it, and then she’d just return. She was bipolar – she was given medication for it and sometimes didn’t take it, because she valued the artistic creativity that being bipolar gave her. She knew what she was doing, and gave a slightly guilty smile – which meant something was going to go pretty wrong any minute. But she also might come up with something wonderfully creative. Most artists are like that inside – but they modify themselves usually, and begin to get boring. She never got boring.

She then had a hysterectomy – extraordinarily she chose to have it by the knife, not the laser – and they can be incredibly damaging. She got in a terrible state. She looked at some gigs she’d done a few months earlier where she’d cancelled at the last minute, then had to rearrange – she said I was lying, that the promoter was stealing money from her, and put something on Facebook that was quite rude. But I never stopped loving her. She’s what an artist should be.

‘She was prophetic’

Catherine Pepinster, religious commentator and former editor of the Tablet

While British politicians shied away from religion in the 1990s – “We don’t do God,” Alastair Campbell said of prime minister-in-waiting Tony Blair – the pop superstars of that era seemed to do God with a vengeance. Or at least adopt him for their own purposes. Madonna played fast and loose with religious imagery, and George Michael took to wearing crosses and later rosaries around his neck while comparing his lover’s gaze as being Like Jesus to a Child. But it was Sinéad O’Connor who did God par excellence, or at least the institution of the Roman Catholic church, denouncing it and rubbishing Pope John Paul II.

When she protested against the church’s cover-up of priests’ sexual abuse of children by tearing a photo of Pope John Paul II into pieces live on US TV in 1992, the gesture scandalised numerous Catholics. Seven years later she outraged many of them again when she joined the Latin Tridentine church – not recognised by the Vatican – and was ordained a priest, something the official church banned because of her gender.

Yet Catholics could not wholly condemn a woman with the voice of an angel. They eventually realised that when it came to abuse, she had been prophetic, speaking out long before the church admitted what was going on. They admired how she became immensely knowledgable about the various inquiries into abuse within the church in Ireland and the US.

In a 2010 conversation published during my editorship of the Tablet, the Catholic weekly, she spoke of the love of the Catholic faith of her childhood: “The people who are now running the business of Catholicism don’t actually seem to appreciate true Catholicism. The love and curiosity I have about religion, and the passionate love I have for the Holy Spirit, come from Catholicism. I’m interested in the idea of the saints, everything about it. I mean, it’s beautiful.”

Like so many of her fellow Catholics, especially women, Sinéad found the church oppressive at times and life-affirming. She recalled the nun who gave her her first guitar, and a priest who listened to her confession, and told her it was blasphemy to tell him how awful she was when God had made her the way she was.

For her, she once said, the Holy Spirit was a bird, free to fly and land where it chose. I hope that Sinéad’s spirit now has that freedom.

‘She coped with sadness and rage through song’

Sharon Van Etten, musician and fan, often covers O’Connor’s 1990 song Black Boys on Mopeds

Sinéad O’Connor was a performer I had admired and looked up to since I was a child, before I ever wrote a song. I wouldn’t fully begin to understand her pain until later in life, as we all have begun to see how mental health can affect our lives when not acknowledged or tended to. Sinéad was able to cope with her sadness and rage through song and performance. It wasn’t only her words of conviction in writing, but her emotional melodies that inspired the way I looked at singing, how to convey feeling in a song beyond a narrative.

My heart is broken for the story of Sinéad that most people don’t know. For the emotional support she wasn’t able to receive as a child and as an artist wasn’t offered by her industry. Hopefully now her story will be examined and told in a way that can shed more light on her life and struggles so she can be celebrated and admired for what she was able to achieve and overcome regardless of those that didn’t try to understand her. Thank you to the sister that gave her a guitar, who gave her a voice when she didn’t know she had one. We have been so blessed.

‘She was Ireland’s warrior queen’

Steve Wickham, violinist for the Waterboys, U2 and others, also played with O’Connor

Sinéad O’Connor’s voice is one of the most extraordinary you will ever hear – whether in full flight as a singer, or full flight as a woman, mother, activist, writer and friend. Sinéad was a keener – crying for Ireland and our woes, our warrior queen. She was intensely spiritual and under the armour was a kind, generous and sweet woman.

I first met Sinéad when she was still in school in the early 80s. She came along to Eamonn Andrews’ recording studio in Dublin to make a demo of her song Take My Hand with our band In Tua Na – she loved being part of it all. She walked in carrying her canvas school bag. I remember her hero Kate Bush’s name carefully etched in marker on it.

Over the years, we became good friends and she moved into a flat nearby in Rathmines. I produced the demo for her first band Ton Ton Macoute, and she asked that I play on her demos in London for her first solo record. This led to us writing a song together for her debut album The Lion and the Cobra called Just Like U Said It Would B. We spent the day writing in underground cellar by the Thames and then back to her flat for a curry and a laugh. She was funny, clever and beautiful. I’m in tears remembering her – and my heart goes out to Johnny and all her lovely children.

‘A small gesture of solidarity had a far-reaching impact’

HIV Ireland

As her global smash hit Nothing Compares 2 U reached No 1 on the UK charts in February 1990, Sinéad appeared on what was, and remains, Ireland’s biggest television talkshow, RTÉ’s The Late Late Show. Wearing a Dublin Aids Alliance T-shirt, she used her platform to highlight the stigma facing people living with HIV.

Dublin Aids Alliance, now the charity HIV Ireland, was then a collective of community and voluntary organisations working with, and advocating for, people living with HIV and Aids. Sinéad’s decision to wear the T-shirt, which she probably considered a small gesture of solidarity, had a far-reaching impact on the community of people living with HIV in Ireland.

HIV Ireland’s community support manager, Dr Erin Nugent, says: “Many people living with HIV recall, years later, the profound impact of seeing Sinéad in the T-shirt and listening to her advocating for people living with HIV and Aids who felt judged, marginalised and frightened.”

Sinéad’s decision to use her platform to highlight such a merciless inequality, was a groundbreaking moment in the fight against HIV-related stigma in Ireland, and she continued to do that throughout her career. In 2007, she participated in HIV Ireland’s Stamp Out Stigma campaign, reading to camera the words of an African woman living with HIV. Stephen O’Hare, executive director of HIV Ireland, says: “She used her voice simply as a means to amplify the voice a marginalised woman of colour living with HIV in a way that was humble and unique to Sinéad.”

‘A true she-punk’

Vivien Goldman, journalist, interviewed O’Connor for Rolling Stone in 1997

“My intention is to live a long life, and keep diaries this time so I won’t forget,” O’Connor stated, poignantly, in her typically revealing 2021 memoir, Rememberings. Her creativity was mesmerising, all the more haunting for being haunted. Was there ever a more naked, vulnerable and still innately political artist? A true she-punk, her mission scoffed at fame; counterintuitive to the general thrust of the music industry, she did everything – the music, the family, the life choices – her own way.

It seemed as if in her combat with the patriarchy and the world’s corruption, she repeatedly performed Easter by serially rising in new spiritual guises: embracing Irish goddess worship, the priesthood, Rastafarianism and, ultimately, Islam. The title of her 1990 album I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, however, reads quintessentially Buddhist and remarkably, her memoir evidences compassion even for her scary mother who brutalised her in several ways – no help with Sinéad’s later diagnoses, including PTSD. One can only wonder: did Sinéad manage to find that same compassion for herself?Yet there was a toughness within. In a 1997 interview, I asked if she had advice for female musicians starting out. Her reply: “Learn how to say no straight off. You don’t have to look like the makeup artist wants. Trust your instincts. You will have to sever professional relationships with people, and you’ve got to learn not to feel like a bastard. At the end of the day, it’s your name on the thing and it’s down to you. Luckily, the first word my daughter learned to say was no.” No one compares 2 Sinéad O’Connor.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Music News Click Here