“Yes, the remains are an antiquity, but they never stop being a person,” she said.

She wrote to the director of the Gwangju National Museum, proposing that “we, as living people, will have to negotiate between our desires to think of them as historical objects, and the respect for the individual person”.

As an artist, she decided to produce a work that could somehow visually reflect the spirits’ preferred resting place outside the museum’s storage.

For this to happen, the image could not be completed by her hands alone; it had to be a collective creation involving elements beyond her control.

Brutal murder of farmers in Philippines changed this artist duo’s perspective

Brutal murder of farmers in Philippines changed this artist duo’s perspective

She borrowed the practice of “encromancy”, an ancient form of divination by ink stains, so that the swirling patterns of yellow green and aquamarine on paper were dictated by invisible forces – as if the spirits were “arranging” the pigment to reveal their wishes.

The resulting panel of marbled paper summons an abstract geographical landscape that could, in theory, indicate the ideal setting for their remains. This gesture could be “a first step to acknowledge the agency” of the deceased, she noted.

The series, titled “A Terminal Escape from the Place that Binds Us”, is part of Porras-Kim’s ongoing investigation of the fraught relationship between historical objects – including human remains – and museums’ conservation doctrines, cataloguing, and indexing and display practices.

Her interest lies in proposing different compromises that cultural institutions can make with the past to be able to accommodate the relics’ intangible, spiritual function as well as their contemporary life inside the storage or in display cases.

At Harvard University’s Peabody Museum, Porras-Kim encountered thousands of objects extracted from the Chichén Itzá cenote, a sacred sinkhole cave used by the Mayans as a place of worship. Originally placed in the cave as offerings to the Mayan god of rain, Chaac, they were now being housed in the moisture-free, temperature-controlled environment.

In Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, she combined copal, found in cenotes, with dust extracted from the museum storage where the Mayan objects are preserved, to create a block that can be doused with rainwater, thus reuniting the artefacts with Chaac’s power.

Kyoto art fair looks to stand out by embracing city’s Zen Buddhist temples

Kyoto art fair looks to stand out by embracing city’s Zen Buddhist temples

This year, the Korean-Colombian artist has been named one of the four finalists for the Korea Artist Prize, a major contemporary art award.

In her latest triptych, The Weight of a Patina of Time, on view at the national museum’s group exhibition, “Korea Artist Prize 2023”, in central Seoul, Porras-Kim’s archaeological reimagining extends to the numerous dolmens found in Gochang, in South Korea’s North Jeolla Province.

Each of its three panels represents different perspectives of the megalithic tomb – including one from the viewpoint of the person buried when dolmens still served as grave markers, another from the present-day point of view where the stones hold Unesco historical site status, and the third from a natural standpoint, indicated by the moss covering the monolith’s surface.

I’m trying to deal with how the ancient past can be better represented in these institutions

Like other projects, the work is a reminder of how an antiquity that was supposed to spiritually function forever is leading a current life in conflict with its original intent.

In another corner of central Seoul, at the Leeum Museum of Art, is Porras-Kim’s solo show, “National Treasures”, where her new works engage in a compelling dialogue with 10 national treasures drawn from the museum’s collection.

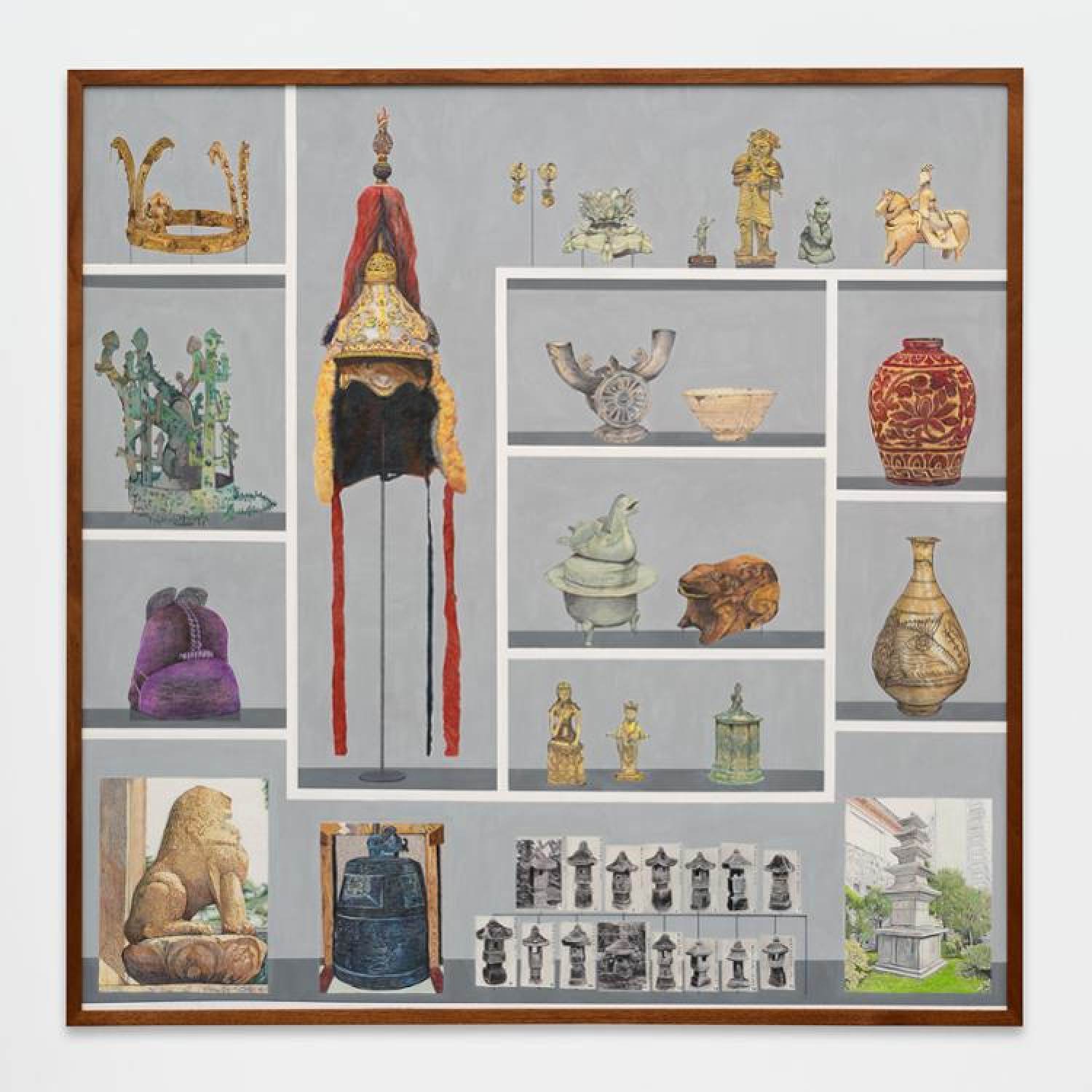

In her photorealistic drawing, 530 National Treasures, the artist summons state-designated treasures from both North and South Korea, arranged in the order of their registration numbers.

Her other piece, 37 Korean Objects Uprooted During the Japanese Occupation, brings together relics presumed to have been extracted from Korea during the 1910-45 Japanese colonial rule.

These works do far more than simply reuniting objects that can no longer be physically present in one place. By laying bare the modern systems of cultural heritage classification, they reveal how the state evaluates and categorises centuries-old artefacts whose perceived functions have changed in the contexts of colonisation and national division.

“All of the depicted historical objects were made before the nation split [into North Korea and South Korea]. What does it mean to have national treasures and decide these different categorisations for them when the [idea of] nation is always moving around? And who decides what becomes a treasure?” she says.

Although her works can be viewed in line with the current push around the world to repatriate museums’ looted cultural heritage, Porras-Kim noted that her artistic mission to honour the ancient objects’ intangible, sacred functions in today’s institutions is much broader than that.

“Restitution is prioritising geography. It’s like physically moving the relics from one place to another. But I think when the objects were brought to the institution, they brought their context as well. So museum conservators can be regarded as their contemporary caretakers,” she adds.

“I’m trying to deal with how the ancient past can be better represented in these institutions.”

Porras-Kim’s works can be viewed at the MMCA’s “Korea Artist Prize 2023” and the Leeum Museum of Art’s “National Treasures” until March 31, 2024.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here