Smokey Robinson rises from an overstuffed armchair and lowers the volume of the Masters golf tournament on the TV in his 11th-floor suite at the Agua Caliente casino.

The 83-year-old Motown legend is here in the desert to play a sold-out gig several weeks ahead of Friday’s release of his provocatively titled new album, “Gasms.” (You know what that’s short for.) But Robinson, who calls golf “the heroin of sports,” drove out early from his home in Los Angeles to squeeze in a round before showtime.

“There’s really nothing like it,” he says of the game, nodding toward his clubs in a corner of the room. “Ain’t s— else you could call me for at 5 o’clock in the morning and say, ‘Let’s go.’”

For Robinson, golf is the most enjoyable part of an overall wellness regime that also includes yoga — he’s been practicing for 37 years — and a diet he says has been free of red meat since 1972. Whatever he’s doing, it’s working: Dressed in high-end athleisure wear, his blue-green eyes so clear that they look like they could chill a drink, this master of the American love song is the picture of health as he discusses “Gasms” and recounts detailed episodes from throughout the career he launched nearly seven decades ago as frontman of the Miracles.

Among the many, many foundational hits he sang or wrote for other Motown acts — and which got him into both the Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame — are “My Girl,” “Shop Around,” “The Tears of a Clown,” “I Second That Emotion,” “The Tracks of My Tears,” “Ooo Baby Baby,” “The Way You Do the Things You Do,” “Get Ready” and “Cruisin’,” the last of which he says he struggled to finish for five years until one December afternoon in 1978 when he found himself driving down Sunset Boulevard with the car’s top down.

“Couldn’t do that in Detroit,” he says with a laugh of the city where he and Motown were born.

A set of luxuriously appointed R&B slow jams, “Gasms” looks back to “A Quiet Storm,” the boudoir-minded LP Robinson released in 1975 after he’d left the Miracles, worked as a Motown record exec, then returned to performing as a mustached solo artist.

“All the guys at Motown were growing beards back then,” recalls the singer, who splits his time between L.A. and Las Vegas with his second wife, Frances Gladney. “Marvin [Gaye] had a great beard. But hair never grows on my face. The mustache was the best I could do.”

Onstage in Rancho Mirage, Robinson’s voice is as soft and silky as the purple shirt he’s wearing beneath a crisp white suit. His set is a well-practiced digest of the classics he recorded at Motown — with whose founder, Berry Gordy Jr., he recently received the Recording Academy’s prestigious MusiCares Persons of the Year award — although he throws in “The Agony and the Ecstasy,” a deep cut from “A Quiet Storm,” at the request of an audience member with a lyric from the song tattooed on her arm.

Smokey Robinson, left, and Berry Gordy Jr. are honored as MusiCares Persons of the Year on Feb. 3.

(Lester Cohen / Getty Images for the Recording Academy)

Did anyone in your life try to persuade you not to call the new album “Gasms”?

I must admit that my wife and one of her daughters, they set up a conference call to tell me I shouldn’t be going out talking about “gasms” and all this. I said, “Why?” They said, “Well, because, that’s just not a cool thing for you to be talking about.” They didn’t say it was perverted, but something like that. I said, “Why does it have to be, though?” A gasm is any good feeling you might have.

Sure — you sing about eyegasms and eargasms. But the first thing anyone thinks of is an orgasm.

Great. That was my plan, man.

At Motown, you were known for writing about romance as opposed to sex. Did you ever want to write about sex?

That message is in there. It’s just not blatant. As a songwriter, I’ve always wanted to write “I love you” different than anybody’s ever said it.

There’s an ageism at work in pop music — in the wider culture, really — regarding who’s allowed to enjoy sex and to talk about it.

I was watching TV recently, one of those talk shows, maybe Wendy Williams. The subject of sex comes up and she turns to this guy in the audience. He said, “Oh, gosh, I’m 60 years old. I don’t think about sex.” What’s the matter with you? Are you kidding me? I understand that I’m 83, and normally that’s an old person in people’s minds. But I feel as good as I felt when I was 40. And I do the same stuff.

What’s old to you?

Probably 100. I tell people: When you’re 20, you can hurt your arm and go to bed; when you wake up, your arm is fine. When you’re 40, you can go to bed and your arm is fine; when you wake up, your arm is hurting. So you have to consciously take care of yourself, which I do because I don’t ever want to be decrepit.

Yesterday, I took my wife to her dentist — very popular dentist, has a wall of all the celebrity people he’s done, one of them being Frank Sinatra. He asked me if I ever met Frank. I said, “Yeah, I met him when I was a kid. Nice man.” But they let him get to the point where Frank could be onstage and he’s singing one song, forgets the words and goes into another song. Even with the teleprompter. I told my wife, “If you ever let me get like that, I’ll kill you.”

That would be the time to hang it up.

It’s over. I’m out there singing “Tracks of My Tears,” and all of a sudden I’m singing “Going to a Go-Go”? I’m done at that point.

Smokey Robinson performs at the Stagecoach Country Music Festival in Indio in 2022.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

You ever use a prompter?

No.

Billy Joel once told me that he uses one even though he knows all the words to his songs. He said he’s hooked on it, that now he feels unsafe without it.

Well, I know Billy, and I feel bad for him if that’s where he’s at. I think the brain is the greatest computer that’s ever been. I could be onstage singing a song and thinking about, “Hey, who is that over there?” But the words are still coming out. They’re all in there.

How did your father age?

My dad was in his late 80s [when he died], but he was always 50. He drove a truck, laid asphalt for the city. He used to love fishing. From the time I can remember, we would go to Canada, to this Black resort up there in a place called Rondeau Bay. My dad would sometimes stay up there all summer fishing. And later on, after my mom passed, he had a girlfriend who worked there, name was Miss Dorothy. When he was 83 or 84, I asked him, “Dad, when you would go up there and stay all summer, did you and Miss Dorothy do it?” He looked at me and said, “Every night.” And this was before Viagra and all that.

How about your mother?

She was sickly. When my mom got pregnant with me, they told her to abort me because she had high blood pressure. Back in those days, Black people ate high blood pressure — hog maws and pig noses and all kinds of s—. And everybody smoked. So she died when she was 43. I was only 10 — it nearly killed me. I thought she was an old lady. But she was just a kid.

Anybody in your life call you by your given name, William?

Before I was about 4 years old, everybody in my family called me Junior. Then my Uncle Claude started taking me to see cowboy movies. I loved cowboys, especially the ones who sang — Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. So he gave me a cowboy name: Smokey Joe. Everybody called me Smokey Joe until I got to be about 12, then they dropped the Joe. And I’ve been Smokey ever since.

Aretha Franklin and Smokey Robinson at the BET Honors in 2014.

(Larry French / Getty Images for BET)

Did you ever want to follow Motown artists Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye when they started making politically inspired records in the ’70s?

Not at that time. I had done a couple before they did that. I wrote a song called “Just My Soul Responding” that was very political about the mistreatment of the Native Americans and the young men going off to Vietnam when they didn’t have to go because it was bulls—. And I used to talk about all that. I spoke in many places. But I didn’t make it the subject matter of my songs. Somebody had to be writing about love.

Were you happy working as a Motown exec?

I was for a minute. My then-wife, Claudette, and I had seven miscarriages because we were on the road — she was the girl in the Miracles — and the road is hard, especially on women. So we’re trying to have babies until finally she came off the road. By this time, the Miracles and I had done everything that a group could do, and I was tired. And I didn’t want my kids not to know me. So I went to the guys and said, “I’m retiring.”

How old were you?

I was 30. They laughed at me. We had just put out “Tears of a Clown,” our biggest record to date. Our money was going up, everything was skyrocketing, so I said, “OK, I’ll give you guys another year,” which I did. Then I retired. Berry had moved Motown from Detroit to Los Angeles, and he put me in charge of the financial office: “You’re gonna sign all the checks.” I actually went home and practiced my signature: William Robinson Jr.

It was exciting for the first 2½ years or so. Then I got to feeling miserable. But I wasn’t gonna tell Berry, because he was counting on me to be there and do this. And I wasn’t gonna tell my wife, because she was counting on me to be at home with the kids. So I had nobody to tell. The Motown office was on Sunset, and on my way home from work, I would stop by the Roxy or the Whisky just to see somebody onstage.

Just to feel some music, you mean.

Absolutely. I was miserable, but I didn’t know anyone else knew. So one day, Berry came to my office and said, “I need you to do something for me.” I said, “OK, man, what is it?” He said, “I want you to get a band, and I want you to go in the studio and make a record, and I want you to get the f— out of here.” I said, “What’d you say to me?” He said, “You heard me. I see you come in here every day, trying to hide behind a smile. But I’m your best friend — you can’t fool me. And when I see you miserable, it makes me miserable. So I need you to get the f— out of my face.” I hugged him.

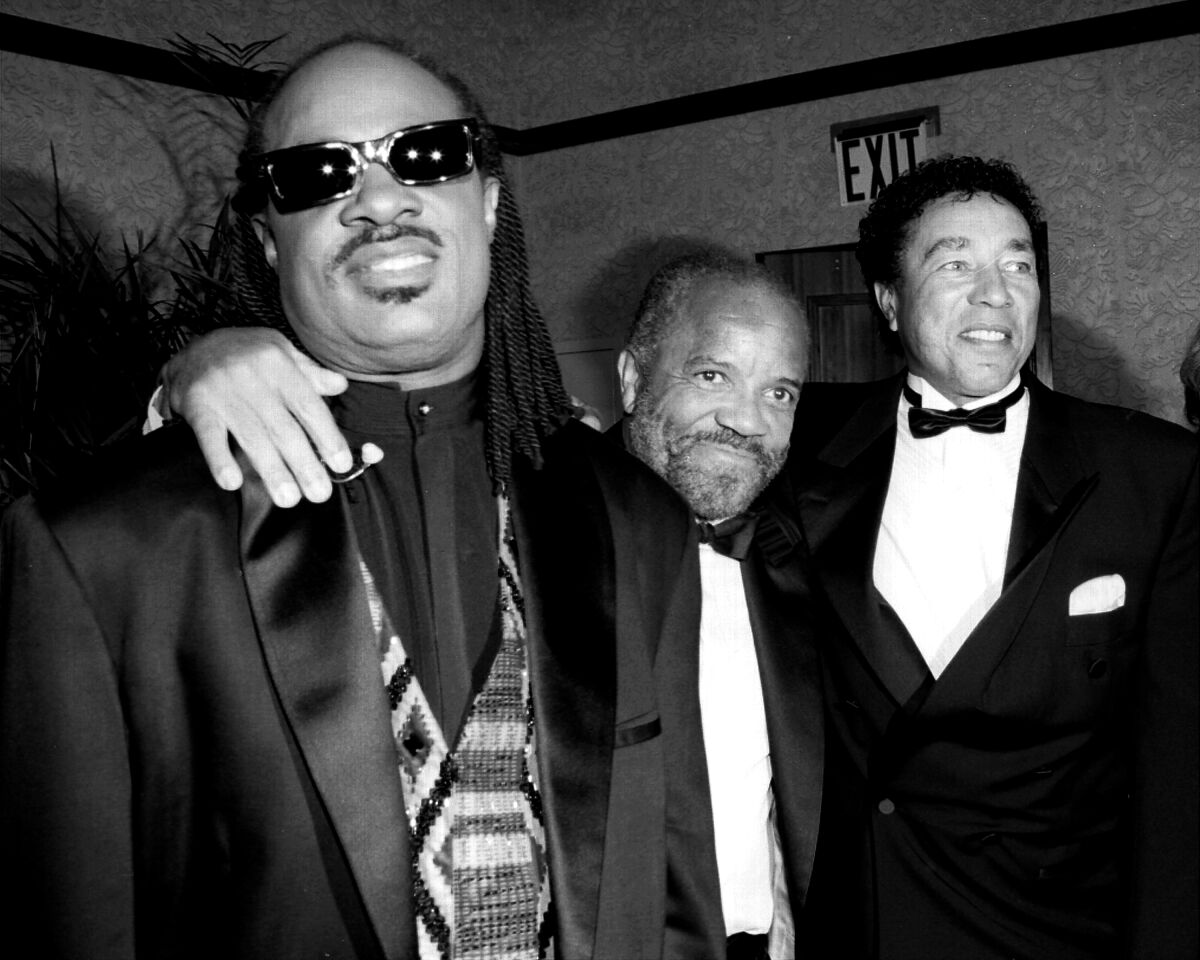

Stevie Wonder, left, Berry Gordy Jr. and Smokey Robinson at the Songwriters Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 1993.

(Richard Corkery / New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

You’ve said that a biopic about your life is in the works.

The script is done. We’ve got it to the people, and they’re reviewing it now.

Why is a movie important to you?

Because I would like my side of my Motown life to be told. But my script isn’t just about music and Motown. It’s about my life and my family. There’s a lot of stuff in there that people don’t know.

You’ve been open about your struggles with drugs. What would someone have found if they’d caught you high?

One of the most embarrassing things in my life happened at the dry cleaners. I had just gotten a divorce from Claudette and I was living by myself, getting high all the time. I went to the cleaners one day and Kenny Edmonds — Babyface — was in there. He came up to me and said, “Hi, Mr. Robinson, I’m Babyface,” blah blah blah. He was a young man just getting into music, doing great, and here I was all f— up. I didn’t want him to see me like that, so I was just trying to get away from him. I apologized to him years later. But I hated myself that day.

Could drugs make you mean?

I was never mean. I was hiding, trying to avoid people. And I’m an extrovert. Only people really, really close to me even knew I was getting high. And the only reason I revealed it is because I thought God would want me to. I wrote a book and put it in there to tell people that you ain’t ever safe.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Music News Click Here