1972 was quite a year for Pula, a port and holiday resort on the Croatian peninsula of Istria. In January a gargantuan bulk carrier named the Berge Istra, billed as the world’s largest ship, slid slowly down the ramp at the city’s shipyard. Six months later, out of town and away from the cranes, the city welcomed another big, bold debutant: the 227-room Hotel Brioni, a sleekly modernist edifice rising above the pines before one of the Adriatic’s most becoming coastal prospects.

This was perhaps the zenith of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a nation steered cannily by its president and de facto dictator Josip Broz Tito through the cold war’s tumultuous waters. Tito’s Yugoslavia pulled off a remarkable balancing act: a communist state that kept itself apart from the Soviet empire, and openly welcomed western businesspeople and holidaymakers.

The Berge Istra was commissioned by a Norwegian shipping line, and the Brioni’s opening was timed to accommodate international movie types arriving for Pula’s high-profile annual film festival.

It’s said that the hotel’s name, after the Italian word for the nearby islands of Brijuni where Tito lived and worked for six months every year, was proposed by Sophia Loren, a serial visitor to the resort.

The inauguration was marred in stereotypical command-economy fashion: the kitchens weren’t finished, and 150 eminent guests had to be bussed into town to eat. But by the following season there would be direct flights to Pula from New York, bringing visitors lured by the Brioni’s highly unusual casino licence — the apotheosis of Tito’s ideologically challenged pursuit of hard currency. Throughout the 1970s, all the big names came to stay: Boney M, Abba, Colonel Gaddafi.

Now, fresh from a €34mn refurbishment by Arena Hospitality Group in conjunction with Radisson, the establishment has been reborn as the Grand Hotel Brioni Pula.

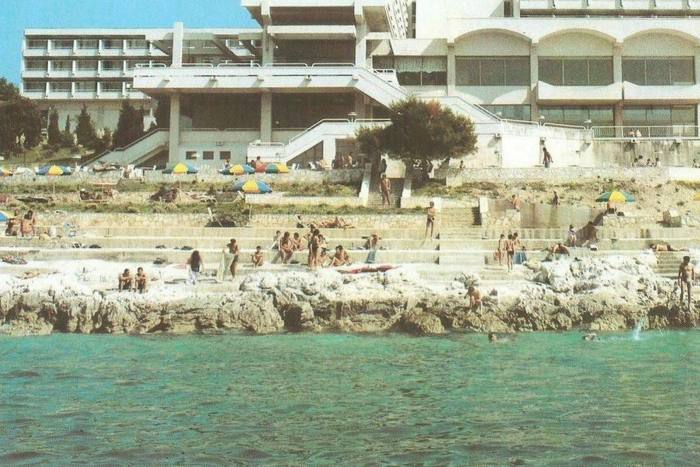

Under a cobalt sky and ringed by shriekingly green lawns, the scene irresistibly recalls those garish, over-coloured postcards from the Brioni’s period pomp, when creaky local Zastavas shared the driveway tarmac with German-registered Mercedes and hipster beach buggies.

Walk through the reception doors, though, and a very different Brioni reveals itself: airy, light and plush, with a lot of blue velvet sofas, a space unrecognisable from the cavernous gloom of the 1972 original, when squat chairs lay forlorn across a sea of dark wood. General manager Alex Živković’s brow furrows when asked what features survived the renovation. “I think maybe the staircase handrails,” he eventually offers.

After Tito’s death in 1980, Yugoslavia began to disintegrate, and with ratcheting tragedy. The economy was already struggling by then, and Istria — a swish holiday spot throughout a convoluted history that since the 18th century has seen it ruled by Venice, Napoleon, the Habsburgs and Mussolini’s Italy before being ceded to Yugoslavia in 1945 — fell from tourist favour.

The Hotel Brioni embodied the decline, slipping from five stars to two during the 1980s as the furnishings and facilities decayed. As a sombre adjunct to this fall from grace, the Berge Istra and its Pula-built sister ship both sank without trace, mysteriously exploding in lonely seas with great loss of life. It was a sorry end for communist Pula’s golden age.

By 2011, online customer reviews offered withering verdicts on the Brioni: “Avoid at all costs, unless you’re looking for a time warp . . . and I’m NOT talking about retro chic.” A local guide who stayed at the hotel around this time says, “You walked in the front door and smelled Yugoslavia.”

Turning this neglected behemoth around must have seemed an almost impossible challenge. But it was one worth undertaking. The location was peerless: two seafront hectares of lawns and shady pine forest. After 50 years, those intersecting oblongs of glass and white concrete were an architectural look whose time had come again. And though a close association with dictatorship might typically deter leisure developers, Tito is still beloved across much of his fragmented former nation.

It turns out that certain elements of the 1970s state-socialist hotel experience lend themselves to a 21st-century luxury makeover. The first is sheer space: 20,000 sq m makes for a lot of grandly proportioned, high-ceilinged communal areas, most conspicuously the opulent lobby bar, blessed — as are most of the catering locations — with a broad overview of the turquoise Adriatic and its majestic attendant sunsets.

Walk out of any lift on the guest floors and a yawning swath of landing opens up; in 1972, these areas were the domain of Soviet-pattern “floor matrons”, employed to look after guests — and keep tabs on them. By way of symbolic evolution, the matrons have given way to unmanned “butler’s corners”, glass booths where guests can buy artisan gin and luxury handbags on an honesty-box basis.

Job-creation overstaffing was a dependable feature of the communist hotel system, and with a rather more service-centric focus the new Brioni has picked up the baton: at 1.2 employees per guest, the hotel’s ratio is very much at the industry’s top end.

The rooms themselves are more modestly proportioned, larger than the originals only because the balconies that fronted them have now been reclaimed behind full-width glass doors. Air-conditioning may have removed the practical necessity for a balcony, but that definitively socialist penchant for fresh air and healthful vigour remains a notable trait. Down in the spangled Adriatic, beyond the Brioni’s slender, 60-metre infinity pool and a rocky foreshore bedecked with cascading sun terraces, a flotilla of paddleboarders strike elegant yoga poses in perfect synchrony. There’s a large gym, overseen by a former professional footballer.

Most compellingly, the spa-therapy ethos embraced by so many communist resorts is paid full tribute. Happily this doesn’t incorporate being pummelled and hosed down by dour orderlies in a white-tiled chamber, as per the spartan archetype.

The indoor glass-walled pool is a clever, seamless upgrade of the Brioni’s slightly municipal original, and the surrounding facilities epitomise high-end, high-tech indulgent wellness — a mood more convincingly inspired by the Romans who settled in Pula, gracing it with the splendid amphitheatre that still hosts the city’s film festival. Above and beyond the usual saunas and steam rooms there’s a salt wall, an ice fountain and a four-stage “water paradise” multisensory shower experience. Precious stones are in extensive evidence, from creams infused with jade, pearl and diamonds to massages with hot quartz rocks and opal gems.

Indeed, a winning mood of unabashed bling pervades the Brioni. The corridor walls twinkle with Swarovski crystals, polished marble and brass are employed with abandon and there’s a lot of gold in the food — even at the remarkable breakfast buffet, where pastries glint with gilded garnish. Gaze along this lavish smorgasbord and spare a thought for whoever took that tragic customer-review photo of their soggy cornflakes 12 years ago, stark and alone on a crumpled paper tablecloth.

At the Sophia steak restaurant, glitziest of the three in-house eateries, the tasting menu is presented with ceremonial panache by a team of black-clad staff, removing huge glass funnels full of smoke from kobe beef tartares before smothering them in truffle shavings. One can’t help but wonder if this ambience was curated with Russian guests in mind. “We had expected them to make up 15 per cent of our business,” says Živković, with a rueful sigh.

Refashioning a communist hotel for the benefit of ultra-wealthy Russians may seem larded with irony, but in some ways it was ever thus. As with most of his ilk, Tito was hardly averse to extravagance. On Brijuni island, the marshal drove about in a metallic green Cadillac convertible — now preserved in a Perspex box in front of his palatial former residence.

The museum within, intended to showcase Tito’s wily geopolitical manoeuvring, offers inadvertent photographic glimpses of a gilded island lifestyle. There he is in a speedboat with Ho Chi Minh, playing snooker on a full-sized table with Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, feeding the elephants that Indira Gandhi donated to his private zoo (one of them is still in residence).

Gazing out from a poolside lounger, you can just make out the southern tip of Brijuni island, nosing into the right-hand horizon. The Brioni’s reinvention is a triumph of chutzpah, an act of cheerful, brash defiance that swims against the tide of boutique hotels, of po-faced minimalism and restraint.

In doing so it taps into the cultures and ideologies that shaped Istria, where pastel Austro-Hungarian mansions look out on to streets labelled in both Serbo-Croat and Italian. Germanic professionalism and expertise, Latin joie-de-vivre, and a communist ruler’s innate sense of might and majesty, harnessed to lure a new generation of big-spending visitors.

Details

Tim Moore was a guest of the Grand Hotel Brioni Pula, a Radisson Collection Hotel (grandhotelbrioni.com). Double rooms cost from €390 per night

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Travel News Click Here