“And I remember Spain,” wrote the Irish poet Louis MacNeice, the “tripper” in the rain in 1938 recalling “sherry, shellfish, omelettes . . . fretted stone the Moor/Had chiselled for effects of sun and shadow . . . churches full of saints . . . Covered with gilt and dimly lit with candles . . . powerful or banal/Monuments of riches or repression . . . the Escorial/Cold for ever within like the heart of Philip . . . and in the Prado half/Wit princes looked from the canvas they had paid for.”

Art has always defined foreigners’ views of Spain. The country evoked in MacNeice’s “Autumn Journal”, its “glory veneered and varnished”, is the one that still bursts into light and colour in the Royal Academy’s stirring exhibition Spain and the Hispanic World, an array of 150 works loaned from New York’s Hispanic Society Museum & Library. They were amassed between 1900 and 1930 by Archer Huntington, heir to a railroad fortune and a man in flight, seeking in exotic under-developed Spain a refuge from the new American industrial society that his family was helping to create.

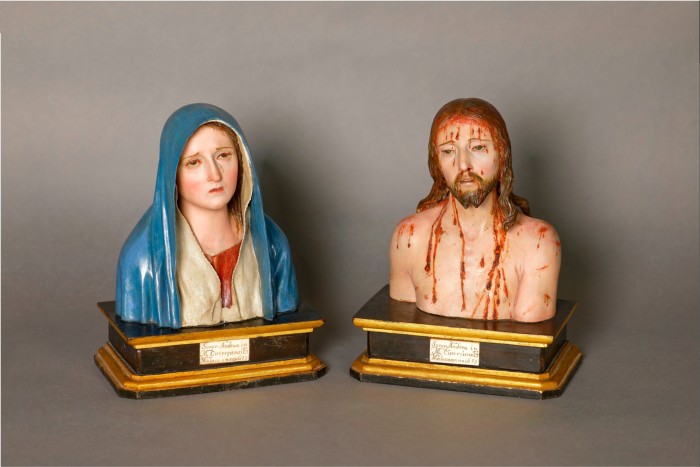

Huntington’s treasure house is an irresistible tonic for a wet London January. Joaquín Sorolla’s serene swimmer emerges from a luminous sea like a modern “Birth of Venus” in “After the Bath”, and polychrome sculptures of a fervent Mary and Jesus carved by 17th-century nun Andrea de Mena gleam in their golden niches. Stiffly determined aristocrats — Velázquez’s moustache-curling “Count-Duke of Olivares”, Goya’s wigged, powdered “Manuel Lapeña” — tower above us, while a laughing “Lucienne Bréval as Carmen” shines in the footlights in Ignacio Zuloaga’s imagined opera production, and José Agustín Arrieta’s bright-eyed black servant in white overalls, “El Costeño” (“The Young Man from the Coast”), proffers a Mexican still life of mango, pineapple, melon and prickly pear.

Huntington was a precocious 12-year-old touring Europe with his parents when he discovered George Borrow’s The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies of Spain (1843) in an English bookshop and fell in love with the idea of the country. As a teenager, he learnt Spanish and later Arabic, then travelled across Spain in the 1890s, supervised an archaeological dig in Seville, befriended bibliophiles and became an expert in manuscripts, ceramics and glassware — though as he told his mother, “I buy no pictures in Spain, having that foolish sentimental feeling against disturbing such birds of paradise upon their perches . . . to Spain I do not go as a plunderer.”

But via dealers in Paris and London he benefited from the exchange of Europe’s Old Masters for America’s new money and was proud that he “could have told where any famous painting of Spanish origin could be found . . . I had seen most of them.” A special coup was acquiring from Joseph Duveen “Portrait of a Little Girl”, one of only two depictions by Velázquez of non-royal children and among his most naturalistic, spontaneous, joyous paintings. The child, solemn yet verging on a smile, her dark hair lavishly rendered with sparkling highlights, was probably the artist’s granddaughter.

The collection’s iconic piece is Goya’s “Duchess of Alba”, the “Black Duchess” attired as a bold urban maja, pointing to the words “only Goya” inscribed in the sand at her feet, which Huntington bought in Paris for $35,000. It distils a romance about Spain — the imperious aristocrat in striking pose, with fiery sash and traditional lace mantilla, standing before an Andalucían landscape representing her estate — while as a portrait of sex, power and the individual spirit, it resonated with Gilded Age America.

The Duchess was an immediate draw when Huntington opened his museum in Manhattan in 1908. But just as revelatory as the art historical trophies was his ethnographic focus, with a vast chronological and material range — bell-shaped “Bell Beaker” Andalucían earthenware from circa 2000BC; Celtiberian metalwork and jewellery; medieval Alhambra silks — and geographical span, including some of the earliest documentation of colonial Latin America.

Giovanni Vespucci’s “World Map”, the master nautical chart from 1526 given to all Spanish navigators, with details of ships, conquests and resources, is displayed in Charles V’s ornamental version. A 1585 watercolour describes the recent founding of Potosí, Bolivia, and its silver mines, against a mountain background with llamas and herders. A map of the river Ucayali, tributary of the Amazon, illustrating local communities along its stretch, was painted by indigenous artists collaborating with Franciscan missionaries. Juan Juárez’s “The Castas: Mestizo and Indian Produce Coyote” (1715), a discomforting portrait of a European-Amerindian father, Mexican mother and their son, reveals viceregal Spain’s obsession with bloodlines and race.

Art was a conduit for propaganda — political, religious or both — on each side of the Atlantic, and some of the greatest paintings here take their drama and passion from Counter-Reformation zeal, led by El Greco’s intensely expressive, elongated “The Penitent St Jerome” and the pyramid of four tragic figures in his “Pietà”. Paintings such as Juan Carreño de Miranda’s frothy, rococo “The Immaculate Conception” were sent to Mexico and widely copied, spreading Catholic messages and teaching European styles.

Some enterprising painters went themselves: Sebastián López de Arteaga, emigrating from Seville to Mexico in 1640, established a tenebrist Baroque school in his adopted home, with violently theatrical compositions exemplified by “St Michael Striking Down the Rebellious Angels”. Soon after painting it, Artegea was struck down himself in a duel and died.

Stark and heightened, Spanish realism links very diverse productions across centuries and continents, and gives the exhibition a hypnotic consistency. The psychological conflicts between the six huge, harshly outlined figures in Ignacio Zuloaga’s “The Family of the Gypsy Bullfighter” (1903), for example, share in secular context the grotesquerie of Ecuadoran sculptor Caspicara’s unforgettable “Four Fates of Man” (1775), polychrome wood, glass and metal figures of a skeleton, tortured manacled villain in hell, and souls in prayer and peace. The gothic chorus of haloed figures staring heavenwards in Miguel Alcañiz’s tempera panel “The Ascension of Christ” (1422-30) seem like ancestors of the stoic Basque sailors lined up on a harbour wall beneath slashing clouds in José Gutiérrez Solana’s “Mariners of Castro Urdiales” (1915-17).

Absent, the elephant not in the room, is Picasso, the artist who wrought from his country’s brutal realist tradition a global revolution in representational painting. Huntington never touched him. Only where works outstandingly depict customs or landscapes did he accept even hints of Modernism: the abstract decorative elements, learnt from Klimt, in the sumptuous embroidered costumes in Hermenegildo Camarasa’s “Girls of Burriana” (1910-11); the cropped compositions and sharp angles of Sorolla’s beach scene “Sea Idyll” (1908). These and the seven-metre gouache sketch for “Vision of Spain” (1912-19), the wrap-round regional panorama commissioned from Sorolla, drench Burlington House’s final galleries in a happy glare.

Huntington said he loved “Vision of Spain” because it memorialised a world “on the verge of disappearing”. His collection reveals as much about 20th-century nostalgia as about how a nation’s history is told through its art: a dazzling double cultural portrait.

January 21-April 10, royalacademy.org.uk

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here