The curtain lifts on a full-figured woman in striped pyjama pants, reclining on a messy daybed. She’s tossed aside a book and turned her thoughts inward, simultaneously careless and theatrical. An unlit cigarette hangs between her lips, Bogart-style, and her uncorseted breasts flop comfortably inside a loose pink cami. The lush verdure behind her might be a real garden or a canvas, since we’re in an artist’s studio — the natural habitat of the women on both sides of the easel.

Suzanne Valadon began artistic life as a model and, even before she aged out of that career, she took up her employers’ tools and showed them how to look properly at women. Though the figure on the chaise in “The Blue Room” evokes Titian’s Venus, Goya’s Maja and Manet’s Olympia, she has none of their voluptuous availability. Valadon’s rumpled goddess looks primed for an evening alone with Netflix and a bag of crisps.

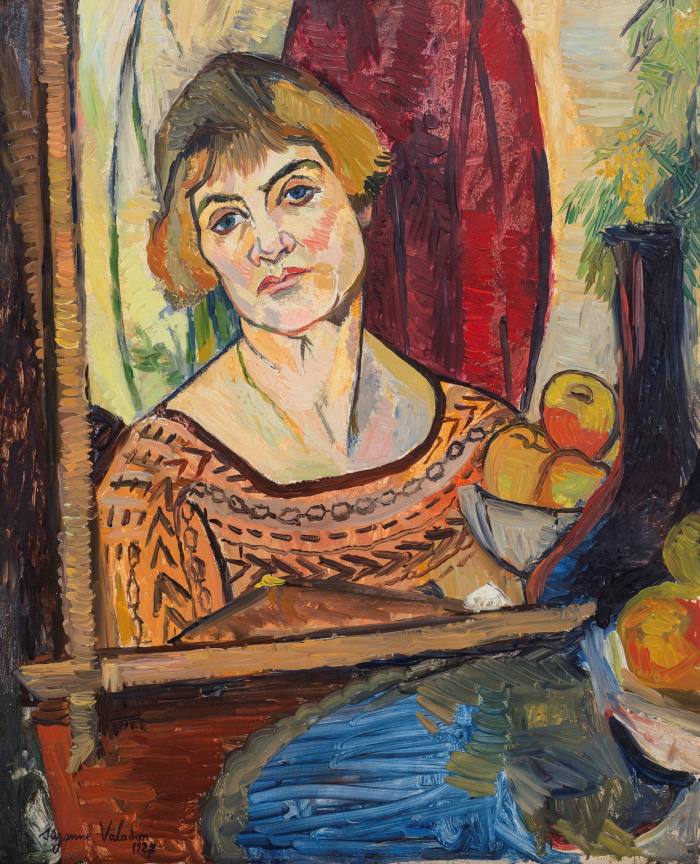

Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel, the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia’s exhilarating tribute to an overlooked master, traces her rise from impoverished childhood to a stint modelling in some of Paris’s most celebrated studios to a flourishing and profitable career as an artist. Male painters often tweaked her appearance as if she were a doll, but in a progression of self-portraits we see a spectacularly specific woman whose moods and experience imprint themselves on her features.

Suzanne (originally Marie-Clémentine) Valadon was born in 1865 in the village of Bessines-sur-Gartempe to an unmarried laundress who had the gumption to look elsewhere for a future. Mother and daughter decamped to Paris’s artistic enclave. “The streets of Montmartre were home to me,” Valadon later recalled. “It was only in the street that there was excitement and love and ideas — what other children found around their dining room tables.” At 17, she was a single mother herself.

The Barnes show begins a little tentatively, with a few obscure portraits and some informative reproductions. That heart-shaped face and slender teenaged body pop up in murals by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and some of Renoir’s most illustrious canvases, including “Dance at Bougival” and “Dance in the City” (neither of which has made the journey to Philadelphia).

“Do you recognise me?” she once asked an interviewer, holding up photographs of both panels. “It’s me who is the dancer smiling in the embrace of her dance partner, and it’s me again as the worldly young woman, gloved to the elbow and in a dress with a train.” Toulouse-Lautrec observed her more closely. They were lovers for a time, but the relationship deteriorates before our eyes: Suzanne’s mouth grows pinched, her brows knit together, her expression sours by the year.

Those years among painters gave Valadon the confidence to take up their profession. Edgar Degas, who admired her “hard and supple” way with line, encouraged her. A relationship with the businessman Paul Mousis provided the means to quit modelling and set up a studio of her own. While male colleagues chronicled the city’s hum in nightclubs, she studied her newly suburban home life, even persuading a housekeeper to pose nude.

Among her first subjects was her son — and future fellow painter — Maurice Utrillo, whose young body she drew in tender yet bold black lines. Valadon’s mother Catherine cared for Maurice, and the artist captures the bond between them: in a poignant gesture of blessing, the naked boy rests both hands on his grandmother’s back as she bends to dry his feet. That scene is a memory, though: the etching dates from 1910, when Utrillo was in his twenties and family life had become a lot more complicated.

By then Valadon, on the verge of divorce from Mousis, had acquired a much younger lover: Maurice’s friend André Utter. In “Adam and Eve” she portrays herself at 44, wearing only a smug smile as she yanks an apple from its branch and the 23-year-old Adam/André grabs her wrist in a vain attempt at caution. Valadon appears content in the role of the original femme fatale, as if the prospect of inducting the first man into sexual knowledge sets her aglow.

The idyll was a turbulent one. After her divorce, painting turned into a financial necessity just as Utrillo’s reputation was starting to eclipse hers. Valadon captures this melange of love, resentment and competition in a pair of extraordinary group portraits. In “Grandmother and Grandson” the dapper, bearded Utrillo leans — lunges, almost — towards us. His large white hand, vehicle of his fame, forms a loose fist and shoots off to one side. Catherine, hands folded in her lap, gazes impassively into the distance in three-quarter profile. The family dog pokes his snout into the claustrophobic scene, as if sensing the disquiet buzzing through it.

In a 1912 “Family Portrait” Valadon inserts her lover into the inner circle, too. She plants herself at the centre of the group, challenging anyone to question her mastery of the medium or the household. Utter stands at the rear, tall, blond and erect. Maurice slumps at the front in an attitude of resigned melancholy. The shrivelled Catherine, ever at his shoulder, completes the pyramidal structure.

By the early 1920s, Valadon’s blazingly distinctive style had won her a steady income and a stellar reputation. Critics lauded her “masculine force” and “virile power”. She painted, one writer declared, “with an energy unheard of in a woman”. It’s hard to pin down what that gendered praise actually meant, since she eschewed the pink gauziness that some males (Renoir, say) slathered on the female body. There’s no sugariness to her nudes or marzipan in her flowers. Limbs look like weighty objects, mottled by greenish shadow. Rooms pulsate with strong patterns and intense colours. You sense the presence of paint as a thick, gooey substance.

In 1927, Valadon produced a magnificent self-portrait of the artist as a woman of a certain age. Heavy lids, angled cheekbones and weathered throat all signal a person who has inhabited her body to the fullest and is now at the peak of her powers. She stares into the mirror with an analytical eye, assessing her reflection with a mixture of candour and pride. Looking back on her career, she once uttered her own version of Caesar’s veni, vidi, vici: “I found myself, I made myself, I said what I had to say.” Respect.

To January 9, barnesfoundation.org

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here